Pakistan’s February 8 Strike and Popular Rejection of Continous Misgovernance

The nationwide strike called for February 8, 2026 is a pointed indictment of a system that has repeatedly denied citizens a meaningful democratic voice and squandered public resources through entrenched misgovernance. Since independence in 1947, no genuinely representative civilian order has been allowed to function uninterrupted for more than a few brief years, with repeated military interventions, manipulated transitions and engineered coalitions hollowing out electoral sovereignty. This accumulated history now converges with the anger that followed the controversial 2024 general elections, which opposition parties, particularly Pakistan Tehreek-e-Insaf and the broader Tehreek-e-Tahafuz-e-Ayeen-e-Pakistan alliance, describe as a stolen mandate.

The strike’s timing is deliberate and symbolic. February 8 marks two years since the 2024 polls, an election widely alleged by the opposition to have been marred by rigging, vote manipulation and systematic interference in the counting and consolidation stages, which TTAP has vowed to commemorate as a Black Day. TTAP, a big-tent constitutionalist alliance led politically by PTI and formally headed by Mehmood Khan Achakzai, emerged precisely from the post-election crisis, uniting parties and groups that believe the present government rests on what they call a usurped public mandate. In recent days, TTAP’s leadership has reiterated that the call for a countrywide shutter-down protest will not be withdrawn under any circumstances, framing it as a peaceful yet uncompromising assertion of constitutional rights rather than a campaign for power-sharing.

The roots of this confrontation go deeper than one disputed election. Pakistan’s political economy has long been defined by an overbearing security establishment, weak civilian institutions and a pattern in which parties are alternately patronised and dismantled depending on their utility to the dominant power centres. Civilian governments have repeatedly been undercut by backdoor engineering, selective accountability and manipulative legal frameworks, eroding public faith in both parliament and the courts. At the same time, chronic mismanagement of public finances, energy, water and basic services has produced inflation, unemployment and deteriorating living standards across provinces, leaving the average citizen with little to show for decades of stability promised from above. When PTI, once itself seen as a beneficiary of establishment patronage, fell out of favour, the scale of coercion directed at its leaders and supporters exposed how fragile and conditional political participation remains in Pakistan’s hybrid system.

The rise and reconfiguration of Tehreek-e-Tahafuz-e-Ayeen-e-Pakistan highlights this convergence of constitutional and socio-economic grievances. The phrase and political imagination of Tahafuz-e-Ayeen is not new in Pakistan’s politics. Earlier initiatives using similar language, including Abdul Qadeer Khan’s short-lived party Tehreek-e-Tahaffuz-e-Pakistan formed in 2012 and dissolved after the 2013 elections, also sought to capitalise on widespread frustration with corrupt elites and institutional decay, though they failed to secure lasting electoral traction. The present TTAP is different in scale and context. It is rooted in an existing mass party, PTI, and it positions itself explicitly as a constitutional resistance front against what it portrays as systemic electoral theft in 2024 and the continued assault on basic freedoms since then. In public statements, TTAP leaders invoke the constitution not as an abstract text but as a social contract that has been repeatedly suspended, amended and selectively enforced to serve narrow power interests.

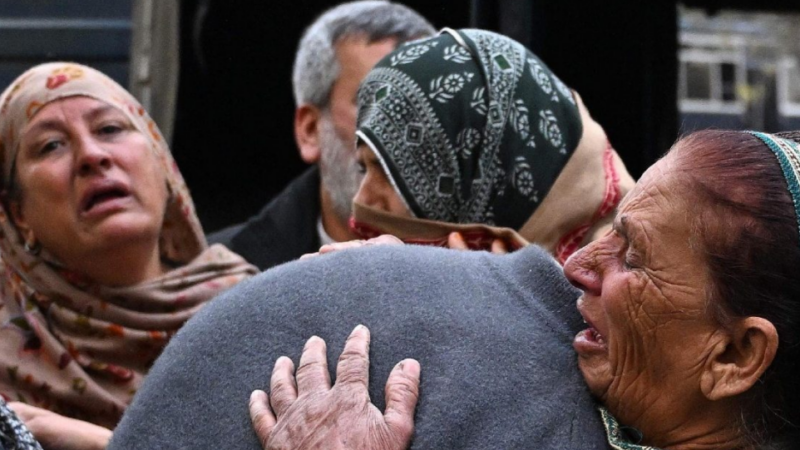

The February 8 strike call therefore blends political and socio-economic anger. TTAP and PTI have urged business owners, transporters, professionals and workers across all provinces to observe a complete shutter-down, arguing that closing markets and halting routine activity for a day is a legitimate, peaceful way to signal that governance without consent has lost moral authority. The parties expect participation from traders, ulema, teachers, lawyers and other segments that have felt the brunt of rising costs, shrinking civic space and arbitrary policing. For many citizens, the strike offers a channel to vent accumulated frustration not only at the disputed 2024 polls but also at electricity shortages, regressive taxation, collapsing public education and health, and the glaring impunity enjoyed by politically connected elites. TTAP leaders, including Achakzai, have indicated that this protest is a first step in a more sustained Jail Bharo Tehreek, signalling willingness to face arrest to press for a reset of the political order.

The state’s response, particularly in Punjab, reveals how deeply securitised the governance mindset has become. Provincial authorities have in recent months repeatedly extended bans on rallies, sit-ins and public gatherings, citing security concerns, effectively treating collective political expression as a law-and-order threat rather than a democratic right. Alongside this, the government has moved to harden the legal and policing framework for handling protests, with proposals and measures that expand police powers, create special mechanisms for riot management and introduce fast-track processes for protest-related offences. The deployment of specialised riot control units and the designation of protest sites as riot zones underline an intent to deter mobilisation through the threat of force and exemplary punishment rather than to engage with the underlying demands.

Crucially, new policing and legal arrangements in Punjab envisage accelerated investigations and summary trials in protest cases, with the aim of securing convictions within compressed timelines. Rights groups have warned that such measures, including provisions that expose not only frontline demonstrators but also those accused of “facilitating” protests to multi-year prison terms and heavy fines, risk criminalising routine political activity and chilling the exercise of fundamental freedoms of assembly, association and expression. By raising the personal cost of dissent, the government hopes to fragment solidarity and discourage ordinary citizens from joining politically sensitive actions such as a nationwide strike that directly questions the legitimacy of the ruling arrangement. This approach may offer short-term control, but it deepens the divide between rulers and ruled. Pakistan faces a severe economic crunch, tight external financing conditions and mounting social stress, all of which reduce the margin for error. Prolonged confrontation, heavy-handed crackdowns and refusal to address demands for electoral transparency and institutional accountability risk further destabilising a system already under strain. Yet the alternative is not passive acceptance of an order viewed as illegitimate. The February 8 strike is thus best understood as a warning shot from a citizenry that has been pushed to the edge by years of misgovernance, disregard for the vote and coercive policing of dissent. Whether the authorities choose to respond with dialogue, meaningful reform and respect for constitutional norms, or double down on repression, will shape not only the immediate outcome of this protest but the broader trajectory of Pakistan’s democratic struggle in the years ahead.