Rumbles of regime change in Afghanistan

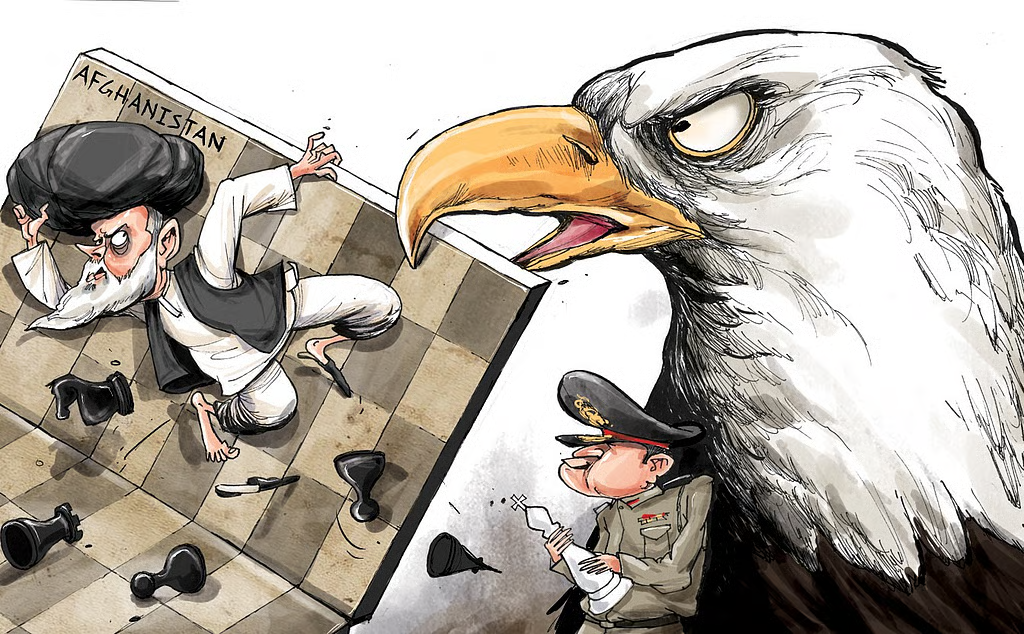

Recent diplomacy hints at Washington’s plan for a change of hands in Kabul. The Türkiye-Azerbaijan-Pakistan axis has a bearing on it. The bus seems to be leaving without Delhi aboard

Indian analysts are ecstatic that New Delhi is playing the ‘great game’ in Afghanistan. The visiting Taliban Foreign Minister Amir Khan Muttaqi’s five-day itinerary had the desired ‘butterfly effect’ on Rawalpindi. Indeed, the Pakistani military crossed the Durand Line even as Muttaqi’s visit was only beginning.

But within the following week, US President Donald Trump signalled he’s watching the developments. American officials contacted none other than Taliban co-founder Mullah Baradar in Kabul to offer mediation. Rawalpindi is moving in tandem with Washington—displaying hard power blending with Washington’s soft power—in a heady cocktail of what Harvard professor Joseph Nye would have called ‘smart power’. Already, two key allies of the US traditionally active on the Afghan chessboard as subalterns—Qatar and Türkiye—kickstarted mediatory efforts. On Sunday, Trump repeated that he could “very quickly” bring about a Taliban-Pakistan reconciliation.

Meanwhile, Afghan-American Zalmay Khalilzad has come out of the woodwork, and is in and out of Kabul. Khalilzad was George W Bush’s special envoy to Afghanistan (and Iraq) as well as ambassador to Kabul and has a unique background. He hails from the Noorzai tribe—usually self-identified as Panjpai Durranis, though many in the Zirak Durranis (tribal confederation of Durrani-Abdali Pashtuns in Afghanistan and Pakistan) dismiss the Noorzai as Ghilzay. Be that as it may, the close partnership between the Noorzai and the Kandahari elite is a fact of political history.

Khalilzad is also a ‘cold warrior’ in the think-tank circuit who served in the Pentagon, represented Big Oil, and enjoys the confidence of the intelligence establishment and the Republican party. He is raring to reclaim his niche in the Trump administration’s plans of encirclement of Russia.

A bit of digression is in order here. The Nato, which has a Black Sea presence in Bulgaria, is slouching toward Transcaucasia—Georgia, Armenia and Azerbaijan. Trump’s mediation between Armenia and Azerbaijan is a step in this direction, which holds the potential for the alliance to wet its toes in the Caspian in future. Beyond lies Central Asia and Afghanistan. In this complex geopolitical backdrop, the Pakistani military’s close ties with Azerbaijan and Türkiye merit attention.

Indeed, the Türkiye-Azerbaijan-Pakistan axis has a bearing on the Afghan conundrum, as Türkiye’s President Recep Erdogan is also tenaciously moulding a ‘Turkic’ identity for Central Asia and Afghanistan. Interestingly, Ghilzay—the largest Pashto-speaking tribe in Afghanistan whose traditional territory extended from Ghazni eastwards into the Indus Valley—are reputed to be descended from the Khalji Turks, who entered Afghanistan in the 10th century.

The Lodhis, who established a dynasty in Hindustan (1451–1526), were a branch of the Ghilzay, who had a glorious tradition of conquest. In the early 18th century, Mir Vais Khan, a Ghilzay chieftain, captured Kandahar and established an independent kingdom there and his son Mahmud proceeded to conquer Persia.

Of course, Trump will not get entangled in ancient history, but has a mind focused on American interests—and, perhaps, his family’s interests. The first US objective is to source Afghanistan’s multi-trillion-dollar mineral resources. The Pentagon is the sole inheritor of geological studies exhaustively conducted by Soviet explorers in the last century in Afghanistan under King Zahir Shah.

Evacuation of Afghanistan’s vast mineral resources was a major obstacle during the US occupation. But Pakistan has thoughtfully proposed a new dedicated deep-sea port at Pasni near Gwadar, linking Balochistan with the world market. Conditions are ripe to act on the Pentagon’s Soviet-era archival materials. Rare earth is beckoning, too.

Secondly, Trump has spoken about Bagram air base and its proximity to China’s border. Equally, resource-rich Central Asia is living in a time warp and engages Washington’s attention, as the designation of a regional envoy signals. Russia’s dominance in the region is perceived to be eroding for a variety of reasons, and there’s disquiet in the Central Asian mind about the precedent set by Moscow to go to war and annex Ukraine’s territory.

The US has an abiding interest in the counter-terrorism operations in Afghanistan. Pakistan is an ally, which is a force-multiplier. The reopening of the intelligence base near Kabul is a dire necessity.

Suffice to say, Delhi has lost the plot. Delhi is cultivating Muttaqi when the train is leaving the station and a long day’s journey into the night is beginning that may end in a regime change in Afghanistan. As Afghanistan’s ruling elite, Taliban has not exactly endeared itself to the international community. The assertiveness of its Kandahar-based supreme leader Hibatullah Akhundzada is not helping matters.

Akhundzada is a rustic cleric and a protégé of al-Qaeda leader Ayman al-Zawahiri, who was killed in Kabul in a US drone strike in July 2022. He is a stubborn, intolerant, and obscurantist figure with no interest whatsoever in an inclusive government or democratic governance, and is preoccupied with Shariah law and petty factional strife endemic to the Afghan way of life. Resentment against his hands-on style is growing. The silence of the graveyard cannot be taken as reflective of the mood in the bazaar.

It is difficult to see how Trump could ever do business with Akhundzada. Yet, he’s a man in a hurry. A 2001-style regime change is unlikely to happen, when Mullah Omar fled on a motorbike from Kandahar as dusk was falling. An ‘in-house’ regime change is a plausible scenario, as splintering the Taliban movement through decapitation of its hardline leadership is a viable option. Anyway, things appear to be moving towards regime change as per some script written in Rawalpindi—with Trump’s blessing—aimed at establishing a ‘broad-based government’ in Afghanistan with minimal bloodshed.

The international community will take a regime change in Afghanistan in its stride. As German Chancellor Friedrich Merz stated recently in an interview, “We’re seeing the temporary end of a rule-based, multilateral world order based on international law. We are in a phase in which the law of the strongest is being enforced in many places.”

Pakistan will not miss such a window of opportunity. The talks in Doha and Istanbul ended inconclusively. Pakistani Defence Minister Khawaja Asif has threatened an “open war”, but he has not elaborated.