Is King Charles overstating social media’s role in Manchester attack?

When King Charles visited Heaton Park Synagogue on Monday, he spoke with people affected by the recent terrorist attack there. He described the incident as “a terrible thing to come out of the blue”. He also made reference to the “ghastliness of social media”, and how it was imperative to “deradicalise people”. In doing so, he blindly followed what has become an unspoken rule in Britain’s elite circles, which is to rapidly change the subject whenever Islam and terrorism are mentioned in the same breath.

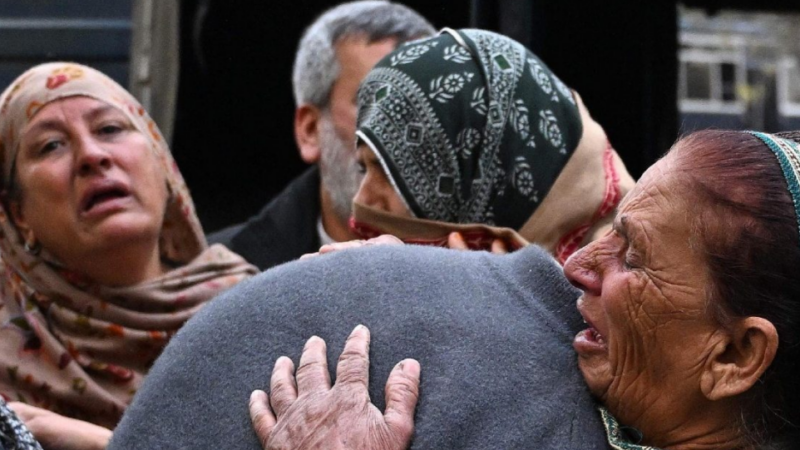

The King’s heart was no doubt in the right place, but his comments are deeply misguided. If all that was known about the Manchester synagogue attack were the monarch’s comments, it might seem it was carried out by a lone individual driven to violence by far-Right 4Chan edgelords. In reality, the perpetrator, Jihad al-Shamie, was a Syrian-born Muslim male who was a fanatical follower of Isis ideology. We know this because he professed his allegiance to the group in a 999 call immediately after the attack. The people he targeted — Jews — are loathed by Isis, which has long urged its followers to kill them, along with infidels, gay people, and apostates. We also know that he wore a fake suicide vest, suggesting that he intended to die in the attack and become a “martyr” to his cause.

It is perhaps unfair to criticise the King, who is an expert on plants and the charms of homeopathic medicine, for lacking expertise on Islamist terrorism. But he ought to have known that the Manchester attack did not “come out of the blue”, as he put it. Rather, it was instead facilitated in part by an atmosphere of antisemitism that has infected British social and political life, expressed violently by extremist Muslims.

Charles, or one of his advisers, could do worse than to look up Daniel Allington’s recent report on Islamist antisemitism, which carefully documents its growing threat in the UK since the Hamas attack on Israel two years ago. “Speakers in certain mosques,” Allington noted, “have promoted the idea that Allah is pleased by the killing of Jews, led prayers for the Mujahideen (without directly naming Hamas), and promulgated conspiracy theories about the 7 October atrocities”. He went on: “The implication often appears to be that attacks on Israeli civilians amount to self-defence.”

The King is half-right about social media, which can be extremely ghastly. Was al-Shamie radicalised on the internet, as Charles implies? And could he have been “deradicalised” if only others had seen the “warning signs” of his extremism and preemptively intervened? Both are important questions, but they are poorly framed.

Al-Shamie had reportedly watched Isis videos via a Telegram channel, and he’d tried to impose his views on others to whom he was close. But there’s no evidence that he was radicalised by watching this material, and it should be obvious to most people that if he looked up those videos it was because they aligned with his way of thinking. Most scholars of radicalisation believe that sustained exposure to extreme online material serves to reinforce or normalise pre-existing radical beliefs. The idea that al-Shamie was somehow an all-round decent, moderate chap who “fell” down a rabbit hole of murderous antisemitism is of course risible, given who he was and where he came from — his father allegedly praised the October 7 attacks. The internet may have accelerated his radicalisation, but it didn’t produce it.

It also seems unlikely that someone like al-Shamie, with all the passionate intensity of conviction that he had, could have been persuaded out of his jihadi mindset, which was bent on murder and suicide. And even if he was subject to a referral to Prevent, it seems highly unlikely that this would have had any impact on his ultimate trajectory. Until Britain confronts the roots of Islamist antisemitism, royal platitudes about “deradicalisation” will remain dangerously beside the point.