Arab-American political force gained prominence this year.

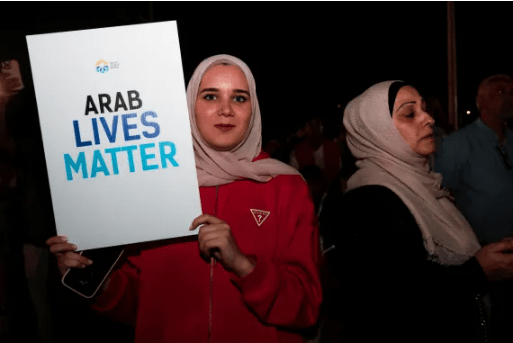

One of the major political developments in the United States that has gotten little attention in the wake of the Democrats’ astounding loss in the November 5 elections is the success of Arab American political organising.

A new generation of political activists has emerged that has earned representation in unprecedented numbers and impact for the 3.5-million-strong Arab-American community in elected and appointed political offices. It also put Arab Americans on the electoral map for the first time by launching the Uncommitted movement during the Democratic primaries and making a foreign policy issue – Israel’s genocide in Gaza – a national moral issue.

The Democratic Party underestimated the power of this new generation and the intensity of citizen anger, which cost it dearly in the election.

What happened in the Arab American community is a vintage all-American tale. They, like other communities, started their pursuit of political impact as a low-profile immigrant group who became dynamic citizens after political developments threatened their wellbeing and motivated them to take action.

Arab American mobilisation traces its beginnings to small-scale participation in Jesse Jackson’s 1984 and 1988 presidential campaigns for the Democratic Party. Jackson was the first serious presidential candidate to include Arab Americans as Democratic Party convention delegates, part of his Rainbow Coalition of “the white, the Hispanic, the Black, the Arab, the Jew, the woman, the Native American, the small farmer, the businessperson, the environmentalist, the peace activist, the young, the old, the lesbian, the gay, and the disabled [who] make up the American quilt”.

His campaign gave momentum to voter registration drives within the Arab American community, which continued in the following three decades. By 2020, nearly 90 percent of Arab Americans were registered to vote. By 2024, the Arab American voter block – in its expansive coalition with other groups – had grown large enough to impact outcomes in critical swing states, especially Michigan and Pennsylvania.

The attacks of 9/11 and the subsequent backlash motivated Arab Americans even more to engage in meaningful politics. Many members of the community refused to live in fear, trying to avoid the intimidation and smears that had long kept their parents and grandparents subdued and quiescent politically.

As Omar Kurdi, founder of Arab Americans of Cleveland, told me, “We were no longer silent because we saw the dangers to us of being quiet and politically inactive. We refused to live in fear of politics. Since then, we have been proud, confident, and active in public. We no longer accept crumbs, but want our share of the pie, and we understand now how we can work for that.”

As a result, over the past two decades, Arab Americans have entered the public sphere and politics at all levels: from local, city, and county positions to state and federal ones.

Elected officials say they succeeded because their constituents knew and trusted them. Candidates who won state and national congressional seats – like Rashida Tlaib in Michigan – inspired hundreds of younger Arab Americans to enter the political fray.

Successful experiences in city politics educated newcomers on how they could impact decision-making, improve their own lives, and serve the entire community. They mastered locally the basics of politics, one Ohio activist told me, “like lobbying, bringing pressure, protesting, educating the public, achieving consensus, and creating coalitions based on shared values, problems, and goals”.

All of this momentum, built up over the years, coalesced into the Uncommitted movement in 2024. As the Biden administration unconditionally supported Israel to carry out genocidal violence in Palestine and Lebanon, Arab-American activists moved to use their newfound leverage as voters in electoral politics.

They joined like-minded social justice activists from other groups that mainstream political parties had long taken for granted – including Muslim Americans, Blacks, Hispanics, youth, progressive Jews, churches, and unions – and sent a strong message during the primaries that they would not support Biden’s re-election bid unless he changed his position on Gaza.

The campaign hoped that tens of thousands of voters in the primaries would send the Democrats a big message by voting “uncommitted”, but in fact, hundreds of thousands of Democrats did so across half a dozen critical states. These numbers were enough to send 30 Uncommitted delegates to the Democratic National Convention in August, where they could lobby their colleagues to shape the party’s national platform.

One activist involved in the process told me they convinced 320 of the other 5,000 delegates to support their demand for a party commitment to a Gaza ceasefire and arms embargo on Israel – not enough to change the party position, but enough to prove that working from inside the political system over time could move things in a better direction.

Intergenerational support and motivation were big factors in the success of the Uncommitted movement. Arab American Institute Executive Director Maya Berry, who has been involved in such activities for three decades, told me that Arab Americans were always in political positions, but in small numbers, so they had little impact. However, they learned how the system works and provided valuable insights when the time came this year to act. She mentioned Abbas Alawiyeh as an example, who co-chairs the Uncommitted National Movement and worked as a congressional staffer for many years.

The Uncommitted movement’s precise contribution to the Democratic Party’s defeat is hotly debated right now. One activist told me the movement “placed Arab Americans at the centre of Democratic Party politics, led the progressives, helped Harris lose in swing states, and nationally brought attention to Gaza, divestment, and moral issues in ways we had never been able to do previously.”

All this occurs in uncharted territory, with no clarity if Arab Americans can influence both the Democratic and Republican parties who might now compete for their vote.

One Arab-American activist in his 30s added, “We are liberated from the Democrats who took us for granted, and we Arab Americans are now a swing vote officially.”

Other activists I spoke to thought the election experience could set the stage for a larger movement to counter the pro-Israel lobby AIPAC, though that would require conquering the next hurdle of establishing Political Action Committees (PACs) and raising substantial funds.

That is a future possibility. For now, it is important to recognise that a national-level Arab-American political effort has been born from the fires and devastation of the US-Israeli genocide in Palestine and Lebanon. Whether it can improve the wellbeing of Arab Americans and all Americans will be revealed in the years ahead.