The political economy of covering the War on Terror in the border regions between Afghanistan and Pakistan

Amid great games and imperial wars, in a region turned upside down in recent times by the United States-led “War on Terror”, few academics and journalists from the Pashtun homelands straddling the Afghanistan–Pakistan border have been able to analyse what has been going on in their mountains. The most widely cited works on the present era come from Western academics, journalists and also military veterans – all part of the extended socio-cultural milieu of the great powers grappling for primacy here, and many affiliated with think tanks and other institutions where various strategies of the war are deliberated.

As the historian Ranajit Guha notes in his essay ‘The Prose of Counter-Insurgency’, such works, even those written by non-officials, are meant primarily for official use – to inform government policies. If sometimes they do incorporate views “from the other side”, they are “prompted by administrative concern”. The prevailing global discourse on the War on Terror can also justifiably be suspected of serving the same purpose: of pushing forward more ways to tame the “uncivilised”.

The War on Terror is not merely a military campaign against Islamist organisations such as Al-Qaeda and their allies; it is also a broader project of influence and control carried out in and by the media and academia. The discourse is as much militarised as the operations on the ground. Much has been written on terrorism, its putative ideological roots in and potential link with Pashtun identity, its fallout and so forth, but seldom have these writings been examined deeply through the lens of the people they have most affected.

Do the media and academia bring to light the suffering of local people caught in the warfare and violence? Or do they perpetuate war by producing a worldview that normalises and necessitates violence? In his book The Dark Side of Journalism: The Culture and Political Economy of Global Media in Pakistan and Afghanistan, the journalist Syed Irfan Ashraf attempts to address these questions, and asks many more. Through the lens of local journalists, the book provides insights into the modus operandi of global media in the years after the September 11 attacks. The author himself started field reporting in 1996, and worked as a journalist with local and national newspapers in Pakistan for nearly two decades.

‘The Dark Side of Journalism: The Culture and Political Economy of Global Media in Pakistan and Afghanistan’ by Syed Irfan Ashraf. Folio Books (May 2023)

Ashraf presents the historical continuity of Afghanistan and the Pashtun belt of Pakistan – the province of Khyber Pakhtunkhwa and parts of Balochistan – as arenas of imperial and later neo-imperial adventures. In doing so, he scrutinises the global media’s role in the War on Terror, exposing the exploitation of local journalists and, in some cases, the fabrication of news. The focus of much of his analysis is the “fixer” – a label, often demeaning, for local journalists assisting international journalists and media outlets, without whose knowledge of local languages and circumstances most foreign journalists are helpless. The word suggests that the fixer’s work is limited to facilitation – logistical support, fixing meetings, translating and transcribing, arranging transportation and so on – when in reality they are engaged in core editorial work, often acting as the main source of information and key point of local contact. These local journalists have been agents as well as victims of the global war fought in their homeland.

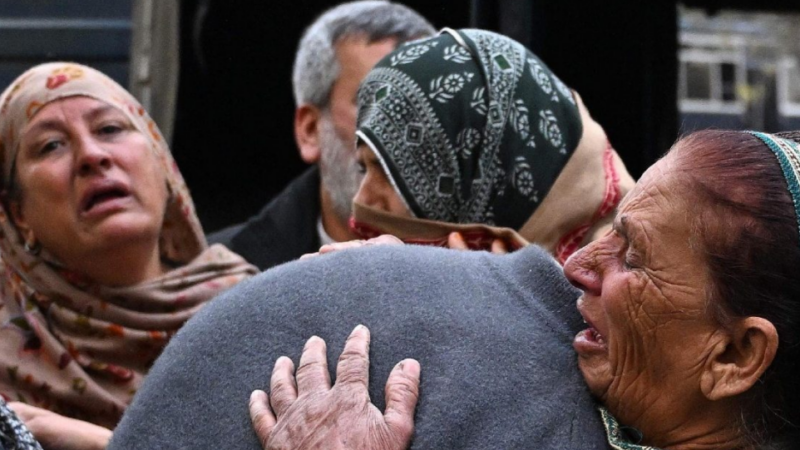

Ashraf draws parallels between the precarious working conditions of local journalists and the living conditions of Pashtuns generally, both defined by the vast power of unaccountable states and global powers. Denied protection and dehumanised, they live a “bare life”, without few or no social and political rights.

The colonial state, the political scientist Romain Bertrand suggests, “remained a state on a war footing,” following on from the “colonial policy of terror”. The Dark Side of Journalism traces Pashtuns’ dehumanisation to colonial times, when much of the Pashtun region was termed “Ilaqa Ghair”, or no-man’s-land, and when great powers fought for control of this strategically important crossroads and frontier. The inhabitants, considered savage tribesmen, were treated as neither subjects nor citizens – an approach largely reproduced by the Pakistan state after the British exit in 1947. The Dark Side of Journalism makes an important point by outlining different colonial policies – for the control of representation, politics and information – aimed at arresting the collective agency of the people in this region, many of which are still in practice.

These policies, Ashraf argues, have hobbled the potential of the Peshawar valley, the capital of Khyber Pakhtunkhwa, without which the area could have fostered new ideas and forms of knowledge production. The city of Peshawar, with its long and rich history of trade and cross-cultural exchange connecting West Asia, Central Asia and Southasia, has an ancient “storytellers’ bazaar”, the Qissa Khwani Bazaar – a reminder of when it was not marginalised from global currents of thought the way it is today. In the years after the start of the War on Terror, the bazaar was a target of frequent bomb blasts and suicide attacks.

Local journalism in the Pashtun areas naturally was stunted as an outcome of such policies. A brief overview of the press in Peshawar, in colonial India and later in Pakistan, establishes that the suppression of the Pashto language carried on with the same rigour after colonial rule to subdue the potential expression of the local populace. Journalistic ventures like the Frontier Post and the Pashto monthly Pashtun – the latter run by the Pashtun leader Khan Abdul Ghaffar Khan – could not avoid the suspicious eye of the authorities. This colonial legacy is clear in the fact that nearly all the Pashto television channels operating in Pakistan today are run by non-Pashtuns.

Local journalists are often compelled to turn their own and their community’s wounds into a source of livelihood. Reporting on the plight of people caught in the war is very often the only avenue open to them as international media outlets especially show little interest in anything else happening in the region. And despite being indispensable to news production, when they work with international journalists they are rarely part of the finished product, rarely given fair credit for their contributions.

Fixers face a huge personal and emotional burden in their work that foreign journalists are typically absolved from. Ashraf narrates an incident from when he worked as fixer with a New York Times journalist on a project about the activist and Nobel Peace Prize laureate Malala Yousafzai. The journalist urged him to make the young Yousafzai appear emotional on camera. When she broke into tears after being asked a question about her father being taken into custody by the Taliban, the camera zoomed in to capture the “cash moment”. Ashraf writes that the New York Times did not carry his name as a co-producer of the resulting documentary, which won awards.

Ashraf recognises that, on the insistence of his foreign employer, he committed an act of emotional betrayal and transgressed journalistic ethics. He also acknowledges that in acting as a fixer on this project, and despite his own marginalised and precarious position, he “contributed to the destructiveness” of the War on Terror.

“Fixers” in conflict regions are often at the command of global corporate media giants, or aids to celebrity television anchors and foreign journalists. Foreign journalists sometimes describe them, with attempted kindness, as “our ears and eyes” – but even this implies that the work of interpreting information, and the finished product, belongs to the foreign journalists.

This diminishment of local journalists ultimately also makes their lives dispensable. The tragic story of the Afghan journalist Ajmal Naqshbandi is one of many examples. In 2007, Naqshbandi and his Italian employer, a journalist working with the daily La Repubblica, were kidnapped along with a local driver on their way to Helmand, in southern Afghanistan, where Naqshbandi had fixed an interview with a Taliban commander. The Taliban demanded that Italy withdraw its troops from Afghanistan, and when refused they beheaded the driver. The Italian journalist was freed in exchange for the release of five jailed Taliban militants, but Naqshbandi remained hostage. The Afghan journalist – a newly-wed and the sole breadwinner for his family – was later beheaded on camera. His death made it clear, Ashraf writes, that to the forces governing global news production “the lives of foreign journalists matter and the lives of ‘fixers’ do not.”

Many local journalists have died away from the eyes of the Western media and rights groups. When the Taliban returned to power in Afghanistan in 2021, many local journalists in grave peril were left to their fate, denied transport and visas to escape. After enduring enormous risks and threats, all local journalists can expect is a pat on the back for being “courageous” and “intrepid”. There is a stark parallel here to the titles given to people from the tribal areas in mainland Pakistan, where they are stereotyped as being hospitable and unthinkingly loyal. One of these titles is baghair tankha sipahi – brave unpaid soldier.

In his interviews with fixers, Ashraf uncovers numerous tragicomic stories. In one instance, a local journalist in Mohmand district, in Khyber Pakhtunkhwa, finds an official spokesperson of the Pakistan military narrating the same information to the press that he had cooked up the previous evening for his employer, a television channel in Karachi, after being caught short on the details of a Taliban attack. Others reveal that it was common practice for foreign journalists to capture footage of the outskirts of Peshawar and portray it as coming from the tribal borderlands and Afghanistan.

Foreign media, in part submitting to audience demand, needed particular kinds of visuals and narratives. They would typically show burqa-clad women, armed men in turbans and stunned children, all to portray the war as a necessary evil, a noble mission for human rights. An interviewee tells Ashraf that he once took a foreign journalist to Dara Adam Khel, a town considered to hold Southasia’s biggest illegal arms-manufacturing units. The journalist was visibly disappointed when the owner of a factory producing handmade weapons solicited help in getting his son admitted to a foreign school. That was not the expected response when the foreign journalist had asked for his opinion on Al-Qaeda and whether he would allow his young children to join “Jihad against the United States.” Fixers reveal to Ashraf that on many occasions they were not paid on account of not producing “shadowy” quotes and visuals.

In their hunt to produce sensational stories on jihad and Talibanisation, international journalists downplayed local resistance to the Taliban, as well as nuanced views about the war and the consequences of systematic violence for local communities. Once labelled “terrorists” in the public mind, many innocent people could be killed not because of acts of terror already committed but, instead, for yet-to-be-committed acts of terror.

This approach systematically reinforced a culture of violence, and so kept feeding the conflict. The Peshawar- based photographer Malik Gul describes how, in Tora Bora cave complex in eastern Afghanistan, there were more reporters – close to 200 – than Western soldiers on the ground in 2001. The foreign media was drawn to Tora Bora in such numbers to report on the area’s Afghan warlords, allied to the US occupation, who were empowered to make up for the low numbers of US special operations soldiers there. Another interviewee shares with the author that he was coldly told to find stories in which “the death toll exceeds 50 people in a single explosion.”

Deconstructing the conflict in the broader context of neo-imperialism and neoliberal capitalism, Ashraf contends that local violence has global connections, rooted in grand imperialist designs. Violence is so interwoven with late capitalism that its production seems as normal as the production of other commodities.

Ashraf deplores the lack of Pashtuns’ own means of representation, which could allow them to assign their own global meanings to the events affecting their everyday lives. It is true that many local journalists were able to earn livelihoods because of the war, but it is also true that many adopted journalism with hopes of abetting progressive political change. They wanted to amplify the voices of their community, show the other side of the picture. However, their aspirations were often handicapped. The Taliban viewed them as spies, the Pakistan state found them inconvenient as it tried to control the narrative around “counter-terrorism”, and the corporate global media saw them as merely ad hoc, dispensable labour. Since 2001, over forty Pashtun journalists have been killed.

Ashraf’s critique of the global media is echoed by an intimate chronicle of Moby Group, Afghanistan’s largest media company. In Radio Free Afghanistan: A Twenty-Years Odyssey for an Independent Voice in Kabul, Saad Mohseni, the group’s CEO and chairman, revisits the birth, rise and struggle of TOLO TV and other media outlets as they have navigated violence, threats and pressure from authorities. Overall, his account, written with the journalist Jeena Krajeski, is a lament for the shattered dream of a civil society in Afghanistan. He stresses that the popularity of the group’s entertainment programmes and fierce investigative reports showed that Afghans – far from being the passive, pathetic figures they were portrayed as in the Western media – yearned for, and cheered on, a bold media of their own.

‘Radio Free Afghanistan: A Twenty-Years Odyssey for an Independent Voice in Kabul’ by Saad Mohseni, with Jenna Krajeski. Harper (September 2024)

Mohseni reiterates what Ashraf industriously brings to the surface regarding the motifs of foreign media coverage. He abhors how foreign journalists, living in or passing through the country, “would craft their narratives of the American war from these Kabul hotels and guesthouses. … largely echoing the message President George W Bush was sending from Washington: the United States as the savior of Afghanistan, rescuing its people from the horrors of a brutal regime, rescuing its women from a brutal culture.” He adds, “there was something made for Hollywood about that narrative.” So many stories were written about Afghans rather than by Afghans.

In the years of the US-backed Afghan Republic, from 2004 to 2021, Kabul was home to many foreign journalists and also varied international consultants whose attitude, Mohseni claims, was condescending at best. The consultants, like foreign journalists, came with ready-made narrative and conceptual templates but little actual understanding of the local context. Their advice offended the Moby staff, since as Afghans they had been on the ground even before the war started whereas the consultants were there to attend or run a few training sessions, travel around the country, bill their clients and leave. In between, they threw buzz words like “democracy” and “women’s empowerment” at everyone they talked to.

While the foreign media was keen to show women trapped in burqas, Moby Group had women, from Kabul and the provinces, as staff members both onscreen and offscreen. On the group’s multiple channels, Afghans watched women question the people in power. The relationship between the Afghan media and Afghans’ quest for civil freedoms can be figured from Moby Group’s decision to launch the news channel Tolo in October 2004, days before the first democratic presidential elections in Afghanistan. The election needed to be “reported by Afghans, in Dari and Pashto, by reporters on the ground in Kabul who knew the city and for whom it wasn’t just a news story,” Mohseni asserts.

For Afghan journalists, Mohseni recounts, the story of the war was very different. Many of them originally were not even journalists. At Moby Group there were many poets, academics and intellectuals who joined with patriotic ambitions and what Ashraf calls a “progressive spirit”. Their position in comparison to that of the foreign media is best described in Mohseni’s words: foreign journalists “had the luxury of beginning to analyse an attack as soon as it happened, for they didn’t need to pause to digest it emotionally.”

It was this attachment that made Moby Group’s work, and that of other Afghan media organisations, more ethical. Moby Group offered life insurance to its employees, and offered jobs to siblings of slain journalists. This stood in complete contrast to the precarious conditions that the global media imposed on fixers.

Local media outlets reporting in Afghanistan’s presidential era showed an alternative image of Afghans and Pashtuns to the world. Here they were indeed laying the ground for a vital component of democracy – a free and fair public sphere. The closure of more than half of Afghan media outlets in the aftermath of Kabul’s fall to the Taliban in 2021 testifies to how such aspirations are always hostage to geo-strategic changes in the neo-imperial calculus. The situation is much the same on either side of the Durand Line: Pakistan and Afghanistan, tied by geography, are equally damned in the great games of the great powers.