Asia’s terrorist surge: Isis-K activates sleeper cells from Pakistan to Russia while Chinese interests are criticized

Using Afghanistan as a base, Isis cells have hit targets in Russia, Pakistan, Iran and Turkey this year, spurred on by outrage over Israel’s Gaza war

Pakistan blames the Afghan Taliban for its inaction against the group, as well as the Baloch militants striking Chinese interests in South Asia

A surge in terrorist plots and attacks carried out by Islamic State through its Afghanistan-based affiliate Isis-Khorasan (Isis-K) this year shows a deadly shift in strategy by the erstwhile caliphate.

After being expelled from strongholds in Iraq, Syria and Afghanistan in 2019, and with its leadership in hiding to avoid assassination by American and Taliban forces, Isis has activated its network of terrorist cells, manned by militants from across Eurasia.

Investigations into lethal Isis attacks over the past three months in Iran, Pakistan, Russia and Turkey revealed that they all involved Isis militants from Central Asia, notably Tajiks.

Turkish prosecutors say Uygurs from Xinjiang were also involved in some of the recent attacks. Isis-K has called for members of the Turkistan Islamic Party, an al-Qaeda affiliate whose stated goal is establishing a caliphate in Xinjiang, to defect.

Using Afghanistan as their homebase and Turkey as a logistical centre, Isis cells have worked closely with various national and regional branches to pull off the murderous attacks on four countries this year.

Terrorism analysts told This Week in Asia that Isis-K had replaced the group’s decimated forces in Iraq and Syria as the point of its jihadist sword.

“All these attacks can be traced back in different ways” to Isis-K, said Riccardo Valle, director of research for The Khorasan Diary, an Islamabad-based security news and analysis platform focused on Afghanistan and Pakistan.

It has been a “major player in galvanising supporters, if not orchestrating attacks abroad”, he said.

Analysts say Isis has sought to cash in on the Israel-Gaza war and the public outrage it has generated across the Muslim world.

“In the macro sense, the international-security environment has markedly shifted” in the wake of Hamas’ attack and the Israeli military’s response, said Lucas Webber, co-founder and editor of Militant Wire, a global terrorism news and analysis provider.

“Jihadists have aggressively sought to tap into resultant grievances to incite supporters to violence and direct external operations,” he said.

Isis-K has emerged as the “most globally-minded branch of Isis in its media and militant operations”, Webber said.

He said it is pursuing “a strategy of regionalisation and internationalisation in its propaganda, domestic targeting of foreign interests and nationals, as well as its external operations.”

Deeply strained relations

The actions of Isis and other transnational groups based in Afghanistan, Pakistan and Iran – including al-Qaeda in the Indian Subcontinent, Tehreek-i-Taliban Pakistan (TTP) and ethnic Baloch separatists who share the jihadists’ logistical networks – have deeply strained relations between the governments of the three countries.

Iran and Pakistan, which have generally enjoyed cordial if not particularly friendly relations, violated each other’s air space in January, striking the camps of Baloch militants who they accused of carrying out recent cross-border attacks.

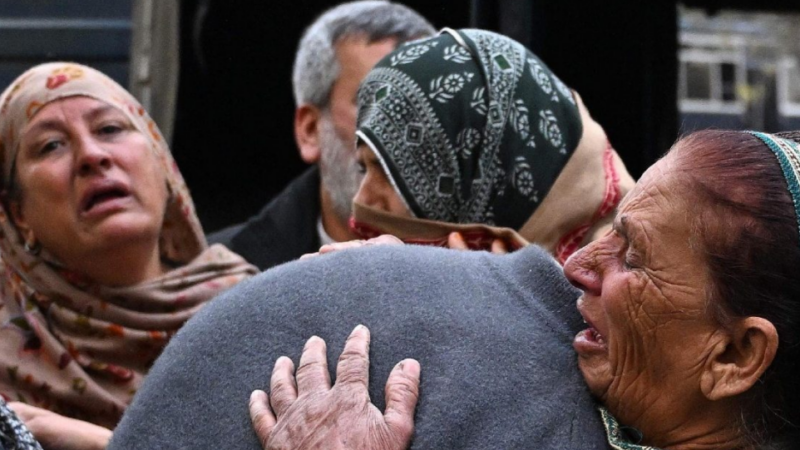

The exchange of fire was initiated by Iran shortly after the killing of more than 90 people in twin Isis suicide bombings in the southeastern city of Kerman on January 3, which targeted a memorial for Qassem Soleimani, the late head of the elite Quds Force, the overseas arm of the Islamic Revolutionary Guard Corps.

Iran also launched retaliatory missile and drone strikes against targets in Iraq and Syria to avenge the bombing of the commemoration for Soleimani, who was killed in a US drone strike in Iraq in 2020.

Pakistan, tired of its supposed Afghan Taliban ally’s refusal to take action against the TTP for launching cross-border terrorist strikes, on March 18 deployed warplanes to hit terrorist camps in southeast Afghanistan targeting the TTP affiliate that had claimed responsibility for the killing of seven Pakistani soldiers, including an army colonel and captain, two days previously.

Defence Minister Khawaja Muhammad Asif also pointed the finger of blame towards Afghanistan’s Taliban regime following a vehicular suicide bombing that claimed the lives of five Chinese nationals working on a hydropower project in northern Pakistan on Tuesday.

Chinese nationals working at Pakistan’s southwestern port of Gwadar were also in the firing line of a Baloch separatist attack on the facility on March 21, with two soldiers being killed before the militants were eventually stopped in their tracks.

Gwadar port is Chinese-operated and serves as a key connectivity node linking Xinjiang to the western Indian Ocean. The two countries are connected by the Karakoram Highway, their sole overland link, where the five Chinese contractors were killed.

“In view of the increase in terrorist incidents, there is a need for a fundamental change in the border situation. The source of terrorism in Pakistan is in Afghanistan and despite our efforts, Kabul is not making any progress in this direction,” Asif said, after attending a top-level security meeting in Islamabad on Wednesday.

As with the TTP, Afghanistan’s Taliban regime has rejected pressure from Tajikistan to prevent cross-border attacks by a Taliban affiliate. A Tajik operating out of Afghanistan was also one of the Kerman suicide bombers, according to Iranian authorities.

Turkish investigators, meanwhile, found that the Kerman attack was carried out by the same Isis cell responsible for a botched attack on a church in Istanbul on January 28. It, too, involved Isis-K militants originating from Afghanistan.

“All of Afghanistan’s neighbours have security concerns with militant groups still based in Afghanistan,” said Maleeha Lodhi, a former Pakistani ambassador to the UK, US and the United Nations.

She said both bilateral and regional pressure “has still not persuaded” the Taliban to crack down on all these groups – some of which have transnational reach and ambitions – “except of course for Isis-K, which it has fought against vigorously”.

The terror attack in Moscow on March 22 “has once again shone a light on the reach of these groups”, especially Isis-K, which has developed the capability to also threaten Western interests “way beyond their base”, Lodhi said.

The war in Ukraine has prevented the kind of East-West cooperation on counterterrorism “necessary to deal with this growing challenge”, she noted, although there is “considerable intelligence-sharing on terrorism even among adversaries”.

“This is needed much more now with rising international concerns with the cross-border activities of militant groups residing in Afghanistan that the Taliban seem unable or unwilling to contain,” Lodhi said.

Threatening Chinese interests

Isis-K has “focused intensely” on the Taliban’s foreign relations with countries such as Russia, China, and Iran, “seeking to create tension and undermine diplomatic ties”, Militant Wire’s Webber said.

To do so, he said it had threatened foreign commercial interests such as Chinese pipelines in Central Asia and the estimated US$62 billion China-Pakistan Economic Corridor, part of Beijing’s Belt and Road Initiative.

Isis-K has “increasingly criticised, threatened, and encouraged supporters to attack a growing list of enemies” including China, Russia, Iran, Uzbekistan, Tajikistan, India and Turkey, he said.

“The attack in Moscow seems to be a sign of things to come and is the continuation of trends already in progress given the uptick of associated external plots foiled and successful attacks,” Webber said.

Being transnational is “exactly” what makes groups like Isis notoriously difficult to track down and disrupt, The Khorasan Diary’s Valle said.

Isis-K runs a network that stretches from Afghanistan and Pakistan to Central Asia and continues to Iran and Turkey, with loose tentacles also reaching into Europe and now possibly Russia, he said.

“Notwithstanding differences and frictions”, regional countries do share intelligence and provide help to each other, which has been vital for counterterrorism in Central Asian countries as well as Russia.

Cooperation against militant groups often follows major attacks, such as the ones in Iran and Turkey, “hence weakening the possibility of dismantling larger networks,” Valle said.

“It would require an integrated mechanism not only between intelligence agencies of the interested countries, but also of nearby and other countries to acquire the larger picture.”

But often, “political frictions and mutual distrust are an obstacle” to such integrated mechanisms, Valle said.

Graeme Smith, a senior consultant for the Crisis Group’s Asia programme focusing on Afghanistan, said geopolitics has “narrowed the space for multilateral cooperation, but a little bit of room can be salvaged” for working across the divides of global competition on “these basic matters of peace and security’.

He said there is “a long history post 9/11” of the US, Russia, China, and even countries such as Iran, finding ways of collaborating against transnational militants.

The US forewarned Iran and Russia about the Kerman and Moscow attacks.

“The attacks in Moscow underline the importance of continuing those relationships on security matters,” said Smith, who is the author of The Dogs Are Eating Them Now: Our War In Afghanistan.

He said “international players” were tilting towards viewing the Afghan Taliban regime as a bulwark against Isis, despite its refusal to accept the demands of neighbours Pakistan and Tajikistan to take action against Taliban affiliates based in Afghanistan.

In December, the UN Security Council called for terrorism monitors to return to Afghanistan for the first time since the Taliban takeover in August 2021.

Later that month, the Security Council also endorsed a report by the UN special coordinator for Afghanistan that called for reform of the 1988 sanctions regime, “which is badly outdated and should be transformed into a set of incentives for the Taliban to be helpful on counterterrorism”, Smith said.

But that would require cooperation between the five permanent members of the Security – China, France, Russia, Britain and US – and he said “it remains to be seen whether that recommendation can be implemented in these tense times”.

Still, the most recent Isis-K attacks “underline the need to work with the Taliban on these overriding security concerns,” Smith said.

He added that the China-led Shanghai Cooperation Organisation should also consider the Taliban’s request to join its meetings, “if only because of the very serious issues on the table related to regional stability”.