Can Taliban in Afghanistan Battle Pakistani Military?

Two and a half years into their reign, the Afghan Taliban have cemented their ultra-conservative rule across the war-torn country but have yet to turn their fighting force into a traditional military.

VOA spoke to analysts who say the former insurgent force does not need to pattern itself after a standard military to effectively counter a mounting security threat from an Islamic State affiliate and tackle growing tensions with neighboring Pakistan.

According to an annual analysis of global militaries by the International Institute for Strategic Studies, the Afghan Taliban have 150,000 active fighters. Military chief Qari Fasihuddin Fitrat told Reuters last year that the regime plans to increase the force by another 50,000, but he did not specify the time frame for doing so.

Since coming to power, the Taliban’s de facto government has not publicly released a defense budget. To formalize their defense forces, they have created three battalions under Special Forces and eight infantry corps.

The military has a variety of armored vehicles, towed artillery, three light aircraft and 14 helicopters, including U.S.-made Black Hawks that it seized after the Afghan National Defense and Security Forces (ANDSF) fell apart amid the chaotic withdrawal of international forces in 2021.

The Taliban also have a few Russian attack helicopters from ANDSF.

Although U.S. forces left nearly $7 billion worth of military equipment in Afghanistan, experts assess the Taliban’s ability to operate some of the sophisticated machinery as limited.

“Without maintenance contracts [and] materials from foreign suppliers who originally equipped the ANDSF, though, it is unlikely they can really use a lot of materials at scale,” Asfandyar Mir, a senior expert at the U.S. Institute of Peace, told VOA.

Adam Weinstein, deputy director of the Middle East program at the Quincy Institute, told VOA that the Taliban face challenges in training their forces similar to those the ANDSF faced.

“They are still dealing with a largely uneducated population that has to be taught sometimes basic competencies of soldiering,” said Weinstein, a former U.S. Marine who served in Afghanistan in 2012.

Insurgency mode

Analysts say despite establishing its rule after the end of the 20-year U.S.-led war, the Afghan Taliban are still in insurgency mode.

“It allowed individual units to, sort of at the tactical level, operate in a semiautonomous way,” said Weinstein, adding that the former insurgents still have “cohesion and decent command and control over their fighters.”

“The biggest strength of the Taliban is their popularity,” said Graeme Smith, a senior consultant at the International Crisis Group.

Smith, who worked as a political affairs officer for the United Nations in Afghanistan between 2015 and 2018, said Taliban forces should not be analyzed like a traditional military, as their numbers change based on local needs.

“During the years of U.S. [and] NATO troop presence, unpublished NATO studies concluded that the vast majority of Taliban fought within 1 kilometer of their own homes. That is to say, locals were going out and shooting at NATO troops, and then going home for lunch and having a home-cooked meal, and then going back out again in the afternoon and shooting some more NATO troops,” Smith explained.

The easy availability of fighters and places to hide, Smith said, give Taliban forces a significant advantage.

Security threats

While the Afghan Taliban have effectively crushed armed resistance, Islamic State Khorasan Province, also known as IS-K or ISKP, poses a significant internal security threat.

“It’s an insurgency which is both malignant and persistent, and it poses an ideological challenge to the Taliban,” said Mir.

The Taliban have killed senior IS-K commanders, eliminated the group’s cells and kept them from holding territory inside Afghanistan.

“So, that’s a testament to the competence of the Taliban security forces,” Weinstein said. “They seem to have good intelligence on ISKP leaders and where the ISKP cells are located, and they seem to be effective in keeping them at bay,” he added.

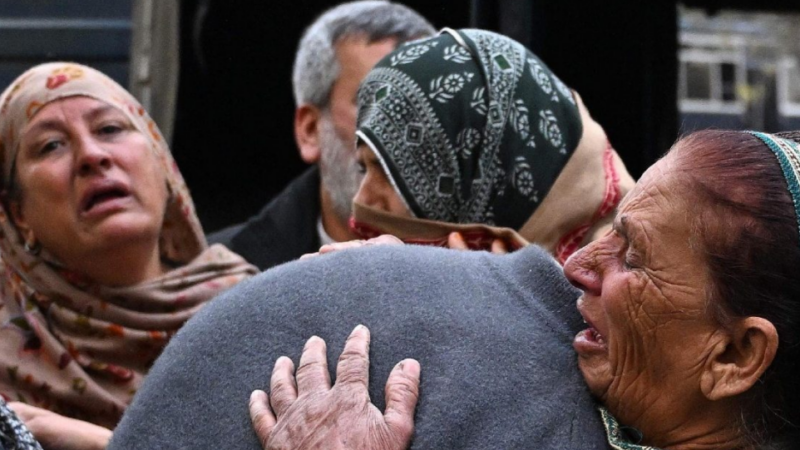

Externally, the Taliban’s Afghanistan faces a threat from Pakistan — the only neighbor Kabul has a border dispute with. Pakistan’s military has conducted strikes twice inside Afghan territory against alleged hideouts since the Taliban returned to power — once in April 2022, and this year on March 18.

Pakistan accuses the Afghan Taliban of giving a haven to anti-Pakistan militants, a charge the de facto rulers reject.

Kabul retaliated to this month’s strike by targeting several Pakistani military posts along the border. In a statement condemning Pakistan’s action, Taliban spokesperson Zabihullah Mujahid warned of “very bad consequences, which will be out of Pakistan’s control,” if Pakistan launches more cross-border attacks.

Fighting Pakistan

Experts VOA spoke to agree that the Taliban do not have the firepower to take on one of the world’s largest, nuclear-armed militaries — but say that Kabul can engage in unconventional tactics against Pakistan.

“They can push back by even doing less to rein in the TTP [Tehrik-e-Taliban Pakistan] or perhaps, giving the TTP carte blanche to engage in even greater attacks [inside Pakistan],” Weinstein said, adding that the Taliban see the TTP as an “insurance policy against the Pakistani state.”

Allowing cross-border terrorism would “certainly raise a lot of international concern,” Mir warned.

As tensions grow between Afghanistan and Pakistan, Smith said Kabul could also scuttle important regional projects. One such project, he said, is the Central Asia-South Asia Electricity Transmission and Trade Project, popularly known as CASA-1000, which will bring electricity from Central Asia via Afghanistan to energy-hungry Pakistan.

The Afghan Taliban could also hinder the land route Pakistan uses for trade with Central Asia, experts say.

A Pakistani Ministry of Commerce delegation met with Afghan counterparts this week in Kabul as bilateral trade drops amid frequent border skirmishes and closures.

Experts agree the chances of the Afghan Taliban getting into a conventional war with a neighbor are slim — but caution the de facto rulers of Afghanistan have a formidable doctrine of asymmetric warfare involving suicide bombers and contingents of locals willing to drop shovels and grab guns when called upon.