To Be a Democracy, Pakistan Needs More Than Just Elections

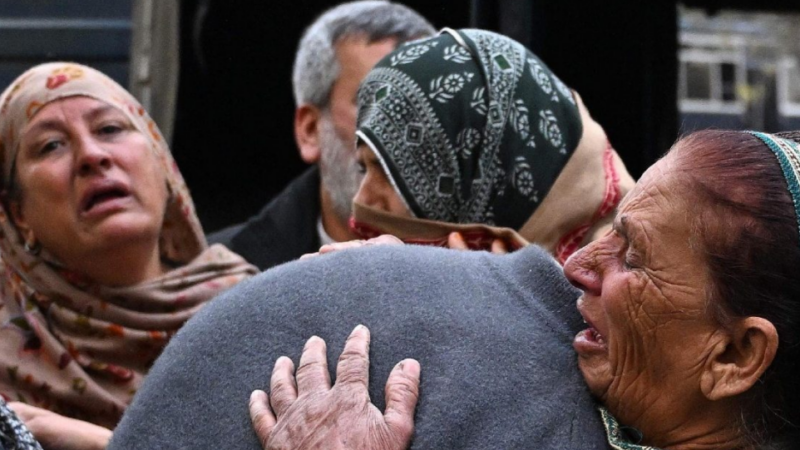

The last 20 months have been a particularly dangerous time in Pakistan. With national parliamentary elections due to take place on Feb. 8, the specter of past political power plays and abuses continues to haunt the present. The political opposition has been marginalized, critics and the media muzzled, and space for civil society has further shrunk.

Former Prime Minister Nawaz Sharif’s Pakistan Muslim League-Nawaz is expected to return to power. A government crackdown on opposition parties, primarily the party of former Prime Minister Imran Khan, the Pakistan Tehreek-e-Insaf (PTI), as well as other opposition parties, has resulted in hundreds of detentions—some on charges of violence. Under alleged duress or inducement, some senior PTI leaders have abandoned the party. Journalists have described intimidation, harassment, and surveillance by the authorities for perceived criticism of the government. Some politicians and journalists have been charged under Pakistan’s vague and overly broad sedition law, based on colonial-era legislation, and dozens tried in military courts in violation of international law.

But we’ve seen this movie before. Decades of manipulation have so eroded the very institutions meant to uphold this democratic privilege and right that elections in Pakistan are rarely “free and fair.” More than three decades of direct military rule—and indirect military control—have thoroughly subverted Pakistan’s experience with democracy. This is the Pakistani politics playbook—form an alliance with the military to come to power, fall out with the military, and get the sack. In between, crack down on the opposition, stifle the media, and threaten any critics.

During the 2018 elections it was Nawaz Sharif’s party on the receiving end along with the Pakistan People’s Party, all to clear the way for Imran Khan, the former international cricket star, to become prime minister. Sharif, who had fallen out with the national security establishment, was convicted of corruption and went into exile. Allegations of vote-rigging and other machinations marred the election. The same colonial-era laws were used against the opposition. Journalists complained of threats and censorship.

Then the tables turned. Following a constitutional crisis and no-confidence vote that ousted Khan’s government in April 2022, clashes peaked in the violent confrontations last May 9, when Khan supporters attacked government and military installations. On Jan. 30, Khan was convicted for violating the Official Secrets Act of 1923 and sentenced to 10 years in jail. Earlier, a court unnecessarily deprived his party of its official electoral symbol, the cricket bat, for not holding internal party elections, which could cost the party the votes of millions of Pakistanis unable to read who only know the emblem.

Meanwhile, Sharif has reconciled with the security forces and other power brokers and returned from exile to form a coalition against Khan’s party.

Both Imran Khan and Nawaz Sharif have disregarded a 2006 political agreement, the Charter of Democracy, a pledge by Pakistani politicians to refrain from colluding with the security establishment to derail democratic processes. By doing that, they—and many politicians who preceded them—thwarted the emergence of a culture and structures necessary for a rights-respecting democracy:

—The relentless pressure on the media has left dozens of journalists arbitrarily detained or forcibly disappeared by a succession of governments.

—The slow strangulation of civil society groups has left few critics to challenge those in power.

—Blocking regular local government elections has denied people the right to representation on local issues.

—Banning trade and student unions has stifled the growth of grassroots political leadership.

—The judiciary’s routine interference in political disputes has sabotaged its independence and resulted in the courts being used for political engineering.

—The Election Commission of Pakistan’s credibility and independence has been eroded through politicized appointments.

—Practices that prevent women from obtaining computerized identification cards effectively exclude more than 10 million women voters.

—Laws that require voters from the Ahmadiyya religious group to effectively renounce their faith to vote exclude the Ahmadiyya community from participating in elections.

These abuses—and not just the merry-go-round of its politics—are the manifestations of Pakistan’s human rights crisis. Unless the country’s leaders change course and foster a culture of political tolerance for criticism and other fundamental freedoms, the present state of political instability, economic debacle, and worsening security will go on, to the detriment of Pakistan’s citizens.

Pakistan’s leaders need to recognize that elections are not only about getting into power, but an opportunity to overcome the politics of division and polarization with a genuine commitment to human rights and democracy.