Liz Truss: Who is the UK’s new prime minister?

Sign up to our free Brexit and beyond email for the latest headlines on what Brexit is meaning for the UK Sign up to our Brexit email for the latest insight Please enter a valid email address Please enter a valid email address SIGN UP I would like to be emailed about offers, events and updates from The Independent. Read our privacy notice Thanks for signing up to the

Brexit and beyond email {{ #verifyErrors }}{{ message }}{{ /verifyErrors }}{{ ^verifyErrors }}Something went wrong. Please try again later{{ /verifyErrors }}

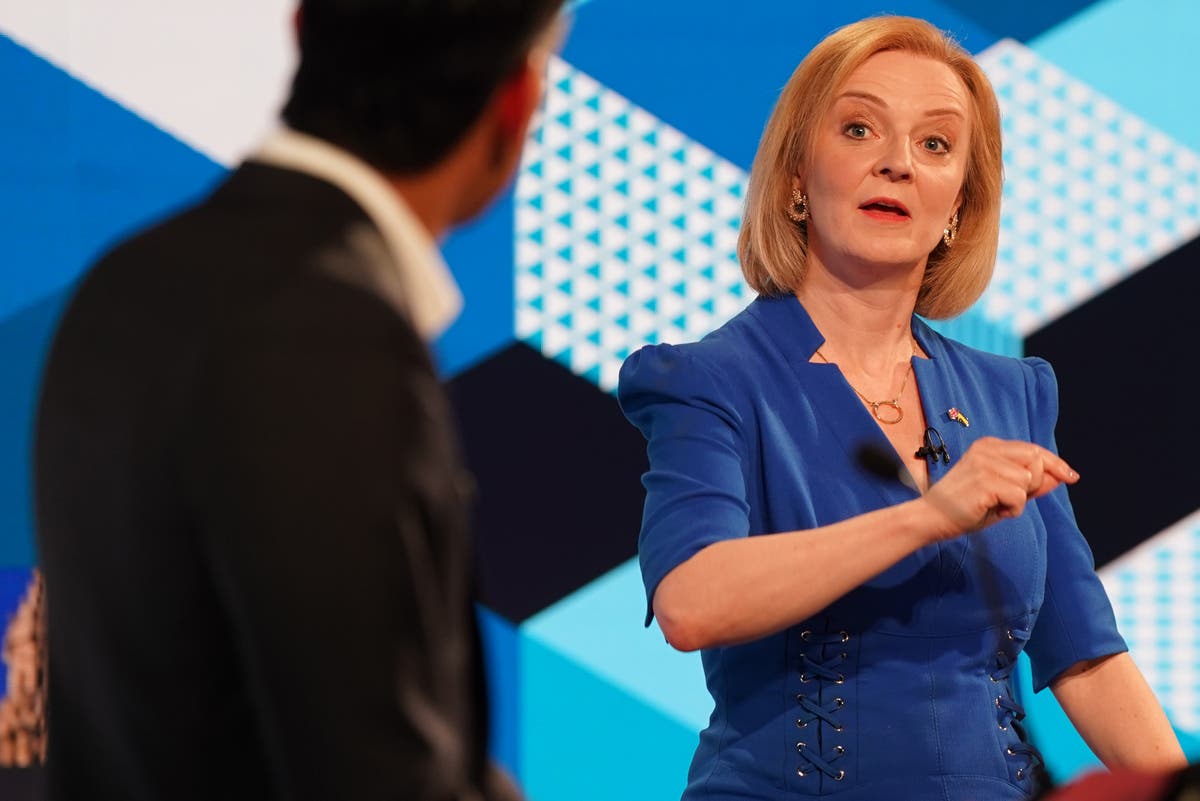

Foreign secretary Liz Truss has been confirmed as the new Conservative Party leader and Britain’s next prime minister, beating ex-chancellor Rishi Sunak in the race to succeed Boris Johnson by securing 81,326 votes from the Tory membership to his 60,399.

When she formally launched her bid for the top way back in July, Ms Truss pledged to set the British economy on an “upward trajectory” by the time of the next general election in 2024.

“We have to level with the British public that our economy will not get back on track overnight,” she said, with commendable frankness.

“Times are going to be tough, but I know that I can get us on an upward trajectory by 2024.”

Positioning herself as an economic libertarian, Ms Truss outlined plans to cancel Mr Sunak’s rises in corporation tax and National Insurance, pledged to increase defence spending to 3 per cent of GDP by the end of the decade and endorsed home secretary Priti Patel’s widely loathed Rwanda deportation scheme for asylum seekers.

Interestingly, she explained away her refusal to join the mass resignations in protest at Mr Johnson’s premiership by saying she was “a loyal person”, a clear dig at Mr Sunak, whose decision to quit alongside health secretary Sajid Javid on 5 July triggered the deluge of resignations that ultimately led to his downfall.

She has certainly been a prominent backer of Mr Johnson in the past and her campaign attracted the support of dogged Johnsonites Nadine Dorries and Jacob Rees-Mogg, even if, like Mr Sunak, she said she would not give the outgoing PM a job in any future Cabinet lineup.

But despite her professions of loyalty, Ms Truss never made a secret of her own ambitions, holding regular “fizz with Liz” socials for her colleagues as well as Monday surgeries in the House of Commons tea room open to MPs with grievances to air, making it clear she always saw herself as leadership material.

Following the completion of the parliamentary stage of the contest, with challenges from the likes of Penny Mordaunt, Kemi Badenoch and Tom Tugendhat seen off, Ms Truss quickly pulled ahead in the two-horse race for Downing Street, painting herself as the true heiress to Margaret Thatcher’s iron legacy while Mr Sunak struggled with awkward questions about his personal wealth and why he propped up Mr Johnson throughout the Partygate furore only to then turn on him.

But Ms Truss too faced plenty of criticism, not least over her failure to address exactly how she proposes to solve the cost of living crisis, having stated her distaste for “handouts”, when the public is facing unaffordable energy bills and runaway inflation this winter.

She was also rightly rebuked for shying away from interviews, notably backing out of 30-minute grilling with the BBC’s Nick Robinson by saying she could not spare the time to have her policies scrutinised.

Mary Elizabeth Truss was born in Oxford on 26 July 1975, her left-wing father John Kenneth Truss a professor of pure mathematics at the University of Leeds and her mother, Priscilla Mary, a nurse, teacher and member of the Campaign for Nuclear Disarmament.

The family moved to Scotland when Ms Truss was four years old and she attended West Primary School in Paisley, Renfrewshire, and then Roundhay School, a comprehensive in Leeds.

At 18, she studied politics, philosophy and economics at Merton College, Oxford, where she was, surprisingly, president of the Oxford University Liberal Democrats.

She switched sides and joined the Conservatives in 1996, the same year she graduated and became a commercial manager at Shell, later serving as economic director of Cable & Wireless and becoming a qualified management accountant.

Ms Truss married another accountant, Hugh O’Leary, in 2000 and the couple has two daughters.

She entered politics professionally when she ran as the Tory candidate for South West Norfolk in the 2010 general election, winning the seat and holding it ever since.

In Westminster, she has held a string of jobs: parliamentary under-secretary of state for childcare and education; secretary of state for environment, food and rural affairs; secretary of state for justice; lord chancellor; chief secretary to the treasury (in which she was succeeded by Mr Sunak); secretary of state for international trade and president of the board of trade.

Liz Truss on her way to Downing Street (Reuters)

Earning the nickname “the human hand grenade” among Whitehall insiders for her habit of blowing things up, before 2022 she was best known for a widely ridiculed rant about British cheese imports during the Conservative Party Conference in 2014, her promise to use barking dogs to stop drugs being flown into prisons by drone and for her bungled response to the right-wing press’s vicious post-Brexit attacks on High Court judges, whom The Daily Mail had branded “Enemies of the People” on one November 2016 frontpage.

Silly pronouncements like describing Britain as “a nation of Uber-riding, Deliveroo-eating, Airbnb-ing freedom fighters” during a speech on the gig economy likewise derailed her mission to be taken seriously, as did a blunder earlier this year in which she confused the Baltic Sea with the Black Sea.

Following such setbacks – and in the interest of gaining a greater degree of control over her public image – Ms Truss became increasingly active on social media, exhaustively documenting her jet-setting diplomatic trips around the world on Instagram and posting endless pictures of herself signing agreements and glad-handing officials, even posing in a British Army tank in a direct nod to Baroness Thatcher.

She found herself facing a genuine military crisis in February as Russia’s war in Ukraine became a brutal reality and travelled to Moscow to meet with her Kremlin counterpart Sergei Lavrov, hoping in vain to convince him to pull back from the brink and walking away with nothing more than some plummy photographs of herself in Red Square sporting a fur hat in warm weather (ideal for the ‘Gram, at least).

Her ongoing condemnation of Vladimir Putin’s actions – which even led Russian officials to explicitly cite comments she made as the reason for their decision to place the country’s military on high alert – saw her enjoy a bump in popularity among Conservatives akin to that of no-nonsense defence secretary Ben Wallace, who declined to run for the party leadership but subsequently endorsed her over Mr Sunak.

Ms Mordaunt and Mr Tugendhat likewise drew attention to their own military credentials in the parliamentary contest, although the economy has swiftly become the defining issue of the race, rather than the ongoing bloodshed in Eastern Europe.

Having won out, Ms Truss now faces a difficult task in uniting her party, not least behind behind the idea that she is the right person to steer Britain through its current wretched economic slump and finally make a success of Brexit (as a reformed Remainer, no less) – and not just a Johnsonite stooge providing continuity and comfort to those still grieving his fall.

Mr Sunak warned that her £30bn of planned tax cuts “on the country’s credit card” would provide only a short-term “sugar rush” and ultimately mean “economic misery” for millions.

That is an accusation she will need to answer seriously if she is to go through with them and again when she squares up to Sir Keir Starmer at the ballot box, as she must before too long.

The woman who left her own leadership launch via the wrong door and tweeted out a promise to “hit the ground” as PM (she presumably meant “hit the ground running”) will also need to cut out the gaffes as she enters No 10 at a time of multiple national crises.