Why death of al-Qaeda’s Ayman al-Zawahiri will have little impact

Once the news cycle moves on from the Kabul assassination, it will be business as usual for the US, the Taliban and even al-Qaeda itself.

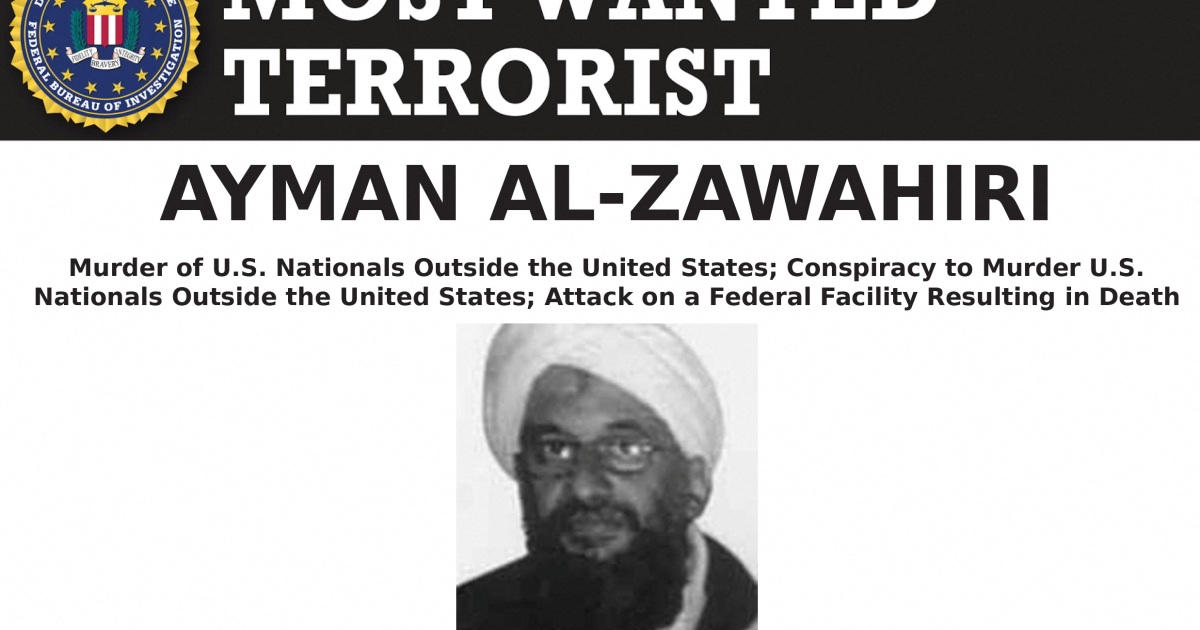

At first glance, the July 31 killing of al-Qaeda chief Ayman al-Zawahiri by a US drone attack in Kabul, Afghanistan, appears to be the most significant setback the group has experienced since the death of its founder, Osama bin Laden, in 2011.

However, throughout the decade he administered al-Qaeda, al-Zawahiri worked to ensure the organisation has all the necessary tools in place to survive his death. As such, while the operation that eliminated one of the organisers of the 9/11 attacks is undoubtedly a major win for the current US administration, it is unlikely to debilitate the group.

Indeed, the fallout from this targeted assassination will be minimal for al-Qaeda. Al-Zawahiri, seen by many as nothing other than a “grey bureaucrat”, can easily be replaced by someone with a similar managerial mindset. He may even be replaced by someone more charismatic, boosting the group’s allure among current and would-be members alike.

On the international level, the drone attack in Kabul will undoubtedly have an effect on the US’s relationship with the Taliban, as well as the future of Washington’s drone operations. However, it is unlikely that it will lead to any significant change or mark a turning point in the regional let alone global status quo.

Impact on al-Qaeda

A terror group tends to survive the death of its leader if it possesses a functioning organisational bureaucracy, an enduring ideology, and communal support. Al-Qaeda benefits from all three.

First, it has a robust operational bureaucracy. Al-Zawahiri did not possess the charisma of his predecessor. But after bin Laden’s death, he created an extensive, self-sufficient bureaucratic system, with clear chains of command, that ensured the group’s fate is not tied to any single leader, including himself. During al-Zawahiri’s tenure, al-Qaeda adopted an expansion model which can best be described as “franchising”. Under his command, the group expanded its reach from Mali to Kashmir with the addition of numerous largely autonomous and financially self-sufficient branches or “franchises”. As these branches are able to continue operations without much intervention from the central command, the death of any leader is unlikely to cause the network to disintegrate.

Second, al-Qaeda adheres to a violent ideology that does not depend on a leader for its articulation or propagation. The set of ideas that guide the group existed long before al-Qaeda, and will undoubtedly continue to be supported by some in zones of failing governance or alienation after its elimination. Al-Zawahiri was no ideologue. And he knew that he did not need to be one to ensure the group’s expansion and longevity. Al-Qaeda’s ideology will continue to attract support no matter what happens to its leaders.

Third, under al-Zawahiri, al-Qaeda enjoyed significant communal support in areas where it has been active. The late al-Qaeda chief was a pragmatist who castigated as counterproductive the ideological rigidity and excesses of the likes of ISIL founders Abu Musab al-Zarqawi and Abu Bakr al-Baghdadi. Unlike them, al-Zawahiri encouraged the group he controlled to cooperate with, rather than fully dominate, locals and local armed groups. This strategy allowed al-Qaeda to expand its reach. In Syria, its affiliate, Ha’yat Tahrir al-Sham, still endures to this day thanks at least in part to Zawahiri’s policies. Likewise in sub-Saharan Africa, during al-Zawahiri’s tenure, al-Qaeda affiliates entrenched their presence by forming local political alliances and garnering support from clan leaders, nomads and farmers. This communal support is unlikely to die solely due to al-Zawahiri’s killing.

Al-Qaeda faced the most significant challenge in its history during al-Zawahiri’s tenure – it was not a US drone raid or the assassination of a leader but the emergence of a breakaway faction in the form of ISIL, which not only recruited members from al-Qaeda, but created a rival, state-centric narrative that undermined al-Zawahiri’s bureaucratic, decentralised vision of a terrorist network.

Given that al-Qaeda managed to survive the existential challenge posed by ISIL, there is no reason to doubt it will also manage to endure the loss of its most recent leader.

Implications for Doha agreement

The US did not find al-Zawahiri in some hidden cave complex in a hard-to-access rural area of Afghanistan. He was found, and killed, in a suburban district of Kabul. This caused many to question whether the Taliban or at least some elements within the group, knew of or facilitated his presence there.

The 2020 Doha Agreement made the American and NATO withdrawal of forces from Afghanistan contingent on the Taliban’s assurances that the nation would not serve as a haven for al-Qaeda or ISIL to launch attacks against the US.

In this regard, US Secretary of State Antony Blinken accused the Taliban of violating the Agreement, by “hosting and sheltering” al-Zawahiri in Kabul, while the Taliban condemned the drone raid, also calling it a violation of the Agreement. These statements are reminiscent of those exchanged in 2011 between the US and Pakistan after bin Ladin was found and killed in a residential district of Abbottabad.

Back then, the US and Pakistan managed to find a way to continue with the modus vivendi they established after airing their grievances. We are likely to witness the same between the US and the Taliban after al-Zawahiri’s killing. Once they are done expressing their grievances about what happened, they will continue with their cautious relationship because they share a common foe: The Islamic State in Khorasan Province, ISKP (ISIS-K), the Afghanistan affiliate of ISIL. As the Biden administration is currently occupied with deterring China and Russia, it still needs the Taliban to deter ISIL, or to at least keep the peace in Afghanistan.

Drone assassinations to continue

Compared with the Trump administration, the number of US drone attacks dramatically dropped during Biden’s tenure – an apparent acknowledgement by the current administration that such raids contribute to grievances that fuel violence, conflict and anti-US sentiments in the long term.

The 2020 assassination of Iran’s Qassim Soleimani in Iraq, for example, deprived it of a charismatic leader and allowed then President Trump to score some easy points with his base at home, but failed to in any way break Iran’s sway over Iraq. In fact, it achieved little more than strengthening anti-US resolve in both countries.

The current US president and those in his administration are undoubtedly aware of this. Nevertheless, the killing of al-Zawahiri in Afghanistan shows that even Biden is unable to resist the temptation of the short-term political gains provided by such high-profile, low-risk drone assassinations.

All this indicates that once the news cycle moves on from al-Zawahiri’s demise, the actors involved will likely continue with business as usual. Al-Qaeda will appoint a new leader and continue operations, the US and the Taliban will hold on to the modus vivendi they established under the 2020 Doha Agreement despite increased tensions, and the US will continue to use drones across the Muslim world, regardless of the negative long-term impact of such operations.

The views expressed in this article are the author’s own and do not necessarily reflect Al Jazeera’s editorial stance.