Gaspar Noé: ‘Watching Gravity on morphine was the best cinematic experience of my life’

Two years ago, Gaspar Noé had the best cinematic experience of his life. He was watching the 2013 blockbuster Gravity on a tiny television from a hospital bed in Paris. The French-Argentine filmmaker had suffered a brain haemorrhage and was doped up on morphine. “I enjoyed that movie so much!” he enthuses in earnest over Zoom. “The whole room was spinning; it was like I was in a womb. I was so happy.” Doing a “load of ketamine” will likely yield similar results, he adds.

Sandra Bullock bobbing about in space was the best thing Noé had laid eyes on since he was eight years old and watching 2001: A Space Odyssey for the first time. “That was one good part of being close to death,” he chirps.

Vortex is another. Noé conceived the film spurred on by his brush with death, which was followed not long after by the deaths of three men whom he called “second fathers”. Vortex chronicles the day-to-day hardships of a married couple at the tail end of their lives. The woman (Françoise Lebrun) is stricken with dementia, unable to care for herself, and the man (director Dario Argento) is increasingly unable to care for her.

Anyone who has ever seen a Gaspar Noé movie will note that Vortex does not sound like a Gaspar Noé movie. Where is the hardcore sex? Where is the shocking violence? Where are the strobe lights?

The poster boy of New French Extremity was anointed 20 years ago, the night his breakthrough film Irréversible debuted at Cannes and became notorious for depicting a nine-minute rape in full. It’s an agonising scene, preceded by another in which a man has his skull bashed in with a fire extinguisher. Who knew bone could crumple like paper? Noé has been offending since, not least with his pornographic 3D outing Love and his LSD trip from hell Climax. A married couple teetering to the end is not his wheelhouse.

But make no mistake: just as all Noé films have a way of clawing under your skin, Vortex – for all its lack of brute assault and cattle-prod sensation – will maul you too. This rheumy-eyed couple are, in many ways, the ideal conduit to feed his latest creation. Old age holds plenty of space for terror. More than dying ever could. And really, death has never concerned Noé or his work. Even Enter the Void, his 2010 trip filmed from the vantage point of a dead man, evolves into a literal journey back to the womb.

In conversation, Noé is equally casual about meeting his end. “Death never feels real. It doesn’t exist. Old age – the decomposition of the brain, the body, the lungs and the bones – that exists. That’s the painful part. Once you’re dead, you don’t suffer,” he chuckles darkly. “These young people want to believe in reincarnation, some soul that’s going to survive past their flesh… stupidities like that. But when people are old, they say ‘I want to sleep and never wake up.’”

When Noé was in hospital post-haemorrhage, he was told there was a good chance he would die in the next four days. At the very least, there would be some brain damage. But death was the last thing on his mind. “How are my loved ones going to deal with all my stuff when I die?” he recalls thinking. “I wasn’t in fear. I was trying to make things happen so that I wouldn’t annoy my loved ones by being brain-damaged.”

Vortex is earning Noé the best reviews of his career, something he attributes to the universality of the subject. “Almost every person in his forties or fifties has dealt with, or is dealing with, his own parents’ ageing.” It is mystifying to him that dementia is so rarely depicted onscreen. “Probably because producers are afraid of losing money doing a movie on a subject that scares everybody.” Noé has memories of his own mother “losing her mind”; some details in the film are autobiographical.

Access unlimited streaming of movies and TV shows with Amazon Prime Video Sign up now for a 30-day free trial Sign up

He explains away the good reviews of Vortex with a shrug: “It’s relatable.” The absence of erect penises onscreen probably helps too. Noé is unphased by the response to Vortex. Disappointed maybe, but not surprised.

You see, Noé likes the bad reviews. He loves the hateful ones. “They’re so stupid,” he giggles. Still, stupid as they may be, Noé understands his critics. “Politicians get insulted very often; directors can get insulted also. It’s part of the game. You want to make movies? Enjoy your haters.” And enjoy them he does. “I love insulting critics when someone writes something bad, and I start insulting the guy in front of all his friends!” He grins at the thought. “This is why I don’t like social networks. For me they are so miserable because you cannot dislike people!”

In modern parlance, Noé may constitute what you call a troll. But call him whatever; he doesn’t give a s***.

Italian director Dario Argento makes his acting debut opposite Françoise Lebrun and Alex Lutz in ‘Vortex’ (Rectangle Productions/Wild Bunch International)

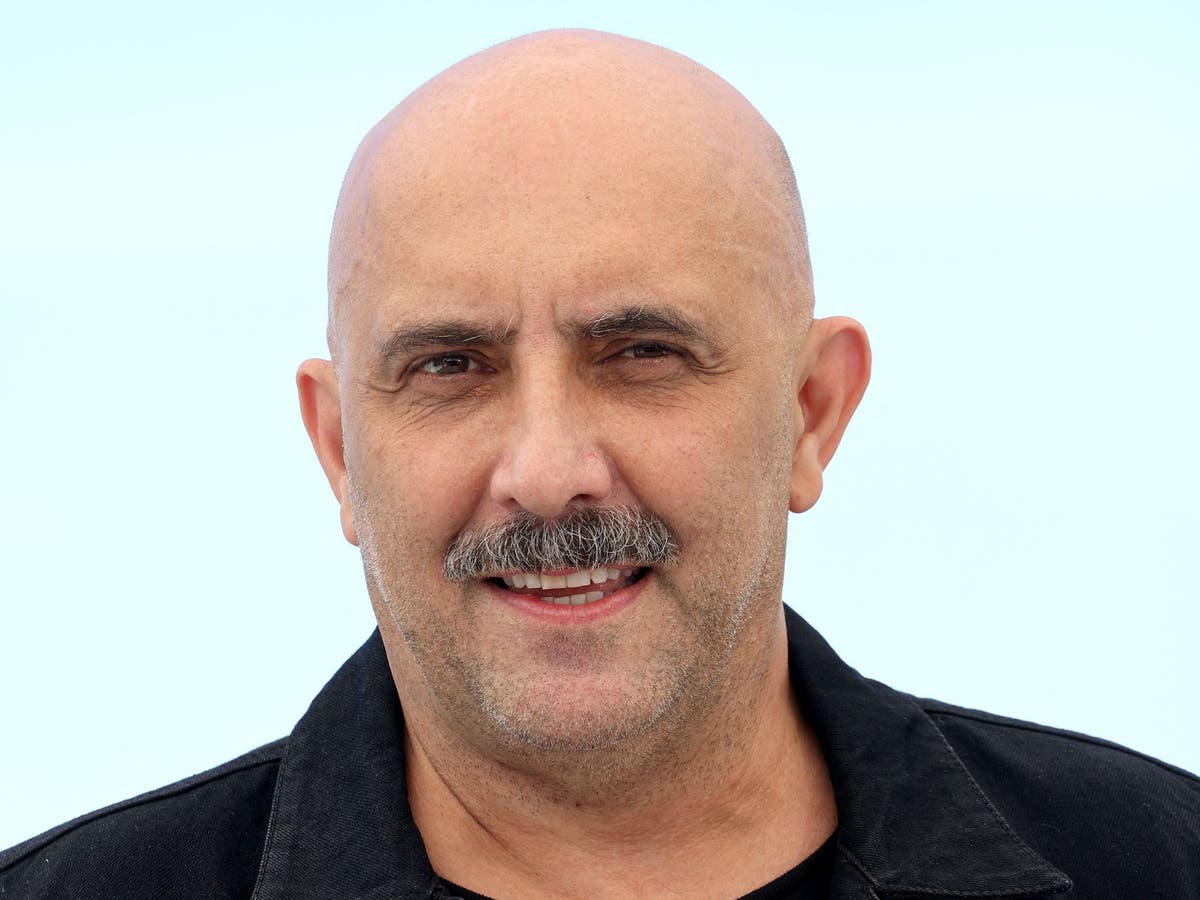

Noé is bald, with a thick moustache that is softened by a neighbouring turf of stubble. He has a heavy brow, beneath which his eyes creep up when he laughs. And he does so freely and often – mostly at his own wickedly morbid jokes. He is expectedly candid. But while he professes a love for provocation, today there seems to be no eagerness to please. Or provoke. You feel that this is simply the world according to Noé.

Piggybacking on the release of Vortex is another feature by Noé: Lux Æterna, an experimental short about the hellish making of a movie, in which Béatrice Dalle plays an inexperienced director and Charlotte Gainsbourg her reluctant star. It is a 54-minute heart attack, thrumming with all the electricity of a brain aneurysm (epileptics, steer clear). I ask if Noé has been on such a nightmarish shoot himself. “Yes – in commercials, people always want to play the boss. I remember shooting one, and the creative directors were putting pressure on me in the name of the client, and the client was a very a stupid client. So I just sent them to hell!” he cackles. “I enjoy it! I enjoy it so much!”

Noé’s words take on a new, irreverent significance when you learn that Lux Æterna was a commercial commissioned by French fashion house Saint Laurent. Noé being Noé, what was intended to be a three-minute video spiralled into an hour-long meta commentary on what it means to make movies today.

If anyone has an opinion on the quote-unquote current state of cinema, it’ll be Noé. “The problem is…” he begins, pauses, and then resets. “It’s like the question, ‘Did Hitler create Nazi Germany or did Nazi Germany create Hitler?’ Do you think the Marvel movies are turning the Americans stupid, or is the whole of America turning so stupid that they need such stupid movies to represent their minds?”

Noé had his own taste of commercial success in 2020, when Love, his 2015 drama, which features many minutes of non-simulated sex, was put on Netflix. There, it found new viewers who were bored in lockdown and, as Noé sees it, really horny. “The movie was successful during confinement because the audience is made of humans who need to masturbate,” he says bluntly. When he was growing up in Paris in the Seventies, he had Playboy. “I needed pretty girls in pretty magazines.” But now news stands have disappeared, and “the pornography you can find on the net is mostly disgusting”, so teenagers seek out erotic movies. “And if it’s on Netflix, they can watch it 10 times in a row,” he says.

“There is also that very stupid Polish movie [365 Days] that was number one. It’s because people need to masturbate. They have a penis or… ” – he hesitates – “the other way around… They just need to play with their toys.” Noé would like to clarify that he did not make Love for that purpose, thank you very much. “It’s sentimental. It’s the sweetest erotic movie, or the sweetest movie you can find that’s close to erotica.”

It is hard to imagine anything turning Noé’s stomach of steel, but he admits to once walking out of a screening himself. Granted, he was a teenager at the time, but still. Noé had gone to see Sam Peckinpah’s 1971 movie Straw Dogs in the cinema, but left during the rape scene. “Straw Dogs shocked me,” he says. Today, the director attributes some of the nausea he felt to a general feeling of weakness that day. “I was probably out partying the previous night.”

Nausea is just one of the feelings viewers reported after seeing the rape in Noé’s own film, Irréversible. The nine-minute-long scene plays out in real time as Monica Bellucci’s character Alex is raped and beaten to unconsciousness in a red-lit underpass at night. It remains his most controversial scene. The film has been called both misogynistic and homophobic in its portrayal of a gay man raping Bellucci’s character.

Do you think the Marvel movies are turning the Americans stupid, or is the whole of America turning so stupid that they need such stupid movies to represent their minds?

“Have you seen the new cut?” Noé asks me excitedly when I bring up the title. “Oh, you must see it! You have to see it.” Irréversible plays back to front: it begins with two men enacting a violent revenge for Alex’s rape, then comes the rape, and before that, normal life. The final scene sees Alex reading blissfully in a park. Irréversible was billed as “a violent trip – from hell to paradise”. The newly released cut flips that chronology. “It is probably more cruel that way, but it’s more clear,” says Noé, adding that the new cut is likely to be more controversial than the original. He seems thrilled by this idea.

Noé hadn’t planned for the rape scene to be so long, but he stands by the decision. “We got money to do the movie from a three-page script and the names of Monica Bellucci and Vincent Cassel,” he explains. The actors were “the magic couple of French cinema at the time, like Tom Cruise and Nicole Kidman”. In the script, the rape was described in four or five lines. “We didn’t know it would last so long at the end, but that was the realistic timing of that scene,” he says.

Albert Dupontel, Monica Bellucci and Vincent Cassel in Noé’s controversial film ‘Irréversible’ (Studio Canal+/Kobal/Shutterstock)

Noé uses this as a diving board to delve into one of his pet peeves about cinema today. “In most movies, when you see people having sexual intercourse, it lasts 10 seconds. They’re like rabbits. The guy comes the moment someone starts penetrating someone, and the scene is over.” He smacks his lips together to make a popping sound to illustrate the finality of it all. “Most art movies are like that.” By contrast, sex in a Noé film is a production of its own. Love features one shot of an ejaculating penis, filmed from the perspective of a vagina.

Why, he asks, when sex is such an ordinary thing, would you shy away from depicting it on screen? “I don’t feel there is a big difference between my genitals and my hands or face. It’s all part of the same body.”

To hear Noé tell it, we’re all prudes. “In England, and even more so in the States, to show a penis is like showing the face of the devil. It’s stupid,” he says with conviction. “There is something really ‘Middle Ages’ in hiding genitals, male genitals mostly.” I ask whether Noé, as a director who is well versed in shooting sex scenes, has witnessed the effects of the #MeToo movement first-hand. The introduction of intimacy coordinators on his sets, maybe?

“I’ve heard about that, but I think it’s more of an American thing, these sexual coordinators,” he says. “Mostly what I’ve noticed is that people have almost stopped having sex in their films. There are barely any sex scenes in movies of the last four years. That’s why when Love or 165 Days [he means 365 Days] comes on Netflix, everybody goes for it.” While various legends of French cinema have spoken out against #MeToo, Noé later tells me: “I am happy all this #MeToo movement happened, because it was needed.”

Noé has been called a lot of things: misogynist, homophobe, provocateur, genius, feminist. Admittedly, that last one is pretty far down the list. “My mother was very feminist,” he recalls. She worked as a social worker. “Each time she would see a couple fighting in the street, she would stop and start insulting the guy and ask the woman if she needed help. I almost saw my mother getting smashed up by some hardcore men.” Noé’s mother, who died in his arms years ago, always advised him to “intervene and save the woman”, whenever they saw someone “being molested or insulted”.

“But,” he continues, “you can tell that I’m –” Noé pauses and comes at it from another direction. “I am a man. I was born a man. I love the company of men, and I love the company of women, but when guys are too mannish, I can become very ‘testosterophobic’. For example, I am happy I never went to military school,” he says. “The man’s world doesn’t fascinate me at all.”

Vortex was released in cinemas on 13 May