French elections: In Paris suburbs, voters face a tough choice between Macron and Le Pen

For Aliti Faya, it’s as if time has stood still for two decades.

It was 2002 when he and other young left-leaning French voters in the Parisian suburb of Seine-Saint-Denis were faced with a tough choice: save the republic by choosing conservative standard-bearer Jacques Chirac, or allow far-right extremist Jean-Marie Le Pen to become president of France.

Then, five years ago, came yet another devil’s choice: the far-right maverick’s daughter and political heir, Marine Le Pen, against the centrist newcomer Emmanuel Macron.

And now, yet again, voters face a rematch on 24 April between the two candidates, Ms Le Pen and Mr Macron, both of whom Mr Faya despises.

Mr Faya, an engineer, and others in this district – considered crucial because its voters and others may swing the election – may very well avoid the polling stations next Sunday, or else cast blank ballots to show their disgust.

Some may even vote for Ms Le Pen in protest against what they describe as Mr Macron’s elitism, neo-liberal economic schemes and policies targeting minorities.

“It’s not the first time we face this situation,” Mr Faya said. “It’s the third time. Some people went to vote for Macron thinking something is going to change. But nothing changed with Macron.”

Aliti Faya during an interview in Seine-Saint-Denis (Borzou Daragahi)

The path to Mr Macron’s victory over Ms Le Pen in the 24 April presidential runoff courses through the Paris suburb of Seine-Saint-Denis and other banlieues like it.

Here, during the 10 April first-round of the presidential elections, about 70 per cent of voters in the mostly poor, largely Muslim and African stretch of the banlieue turned up to the polls to vote, overwhelmingly for the leftwing candidate Jean-Luc Melenchon.

He received 49 per cent of the vote across this French department and as high as 62 per cent in some subdistricts such as Ile Saint-Denis, a working-class island on the River Seine. Overall, 7.7 million French voters supported Mr Melenchon, who placed third in the nationwide balloting.

It’s the same situation as the previous election. People are fed up Hakima Khelfa, Sorbonne University

Those voters, who tend to be younger and more ethnically diverse, are now up for grabs. But while they came out in droves on 10 April, many now voice despair, resentment and anger bordering on rage at Mr Macron.

“This is a tragedy!” said Hakima Khelfa, a political scientist at Sorbonne University who studies Ile Saint-Denis’s unique citizen-run local government and works as a political outreach coordinator for the municipality. “It’s the same situation as the previous election. People are fed up.”

There is a widespread perception that Mr Macron is a tool of the rich and an elitist who sneers at the people here, barely considering them part of French society.

Macron meets residents during a campaign trip in Le Havre, 14 April (Reuters)

Indeed, in the past couple of years of his presidency, Mr Macron has veered to the right, advocating harsh policing and anti-Muslim policies that targeted France’s largest religious minority.

Mr Melenchon, on the other hand, has been hailed by supporters for seemingly embracing the people of the banlieue as fellow citizens, or at least speaking to them in the same way he talks to other voters.

“Melenchon listens to people; Macron has mostly contempt,” said Marie Anquez, a deputy to the mayor of Ile Saint-Denis.

“For Macron the people who live in the banlieues are a problem. Melenchon doesn’t consider them a problem, but a resource.”

People walk through the streets in Seine-Saint-Denis (Borzou Daragahi)

Seine-Saint-Denis is one of the most densely populated regions of western Europe, with nearly 7,000 inhabitants squeezed into every square kilometre. Popularly known as “the 93” for its postal code, it is among the most immigrant-heavy regions of France.

It is rife with social problems, including drug trafficking, and streetside dealers openly ply their trade on street corners and small parks, even visible from the windows of the town hall.

Many families are headed by struggling single mothers. Inflation and stagnant salaries have eaten away at residents’ purchasing power, and concerns among voters about the cost of living are prevalent. Residents complain about police brutality, racism and discrimination.

“Macron has done nothing for our purchasing power; the minimum wage is not enough,” said Karim, a civil servant who declined to give his surname. “Macron did everything for the rich.”

He said he would either stay home, cast a blank ballot, or even consider voting for Ms Le Pen. “But Macron, no!” he said.

He predicted that people in his district would abstain on election day or even back Ms Le Pen, “not for her ideas, but because they are so unhappy”.

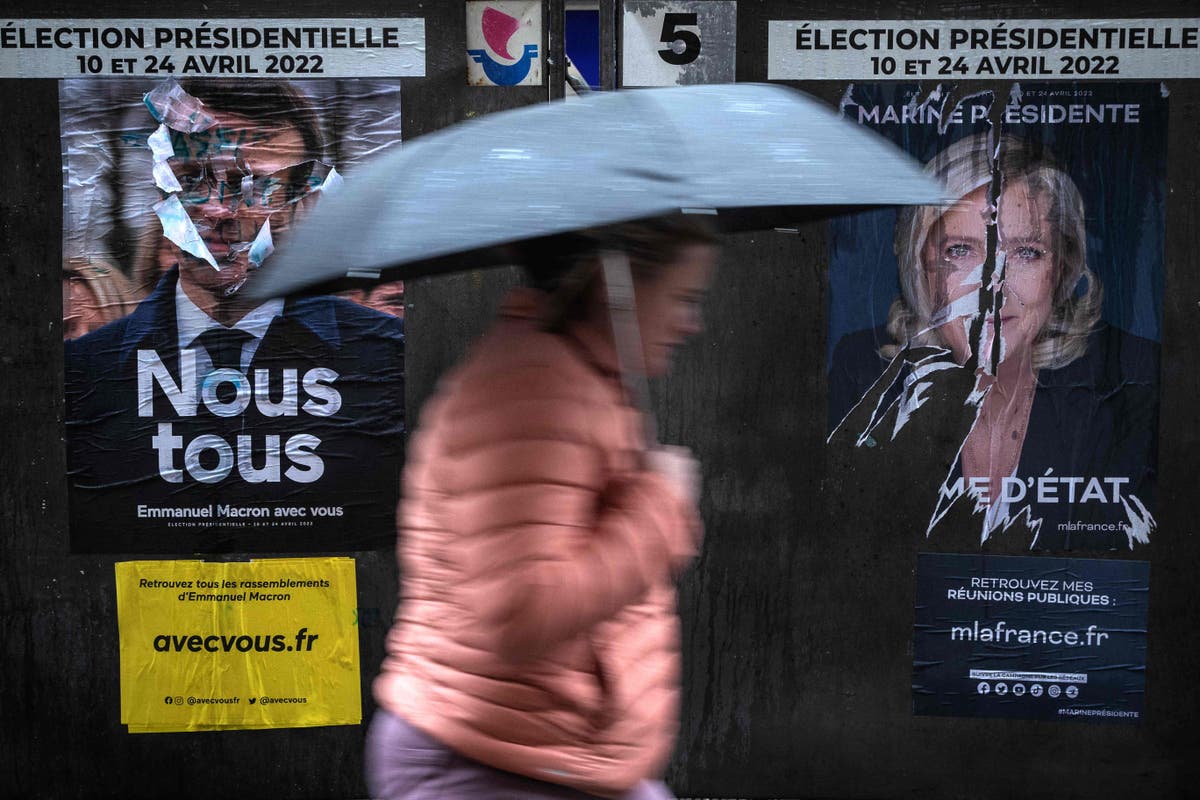

A woman walks past posters for the two candidates in Paris (AFP via Getty Images)

Seine-Saint-Denis has also been a region known for fostering violent Islamic extremism, and in November 2015, it was the scene of a ferocious shootout between police and Isis militants suspected of involvement in a series of suicide bombings days earlier.

But it is also a region of hope, cultural vibrancy and social experimentation. Accessible to central Paris via the crowded regional rail line, it is home to the office maintenance staff, drivers, house cleaners, clinicians, security guards, manual labourers and UberEats gig workers who make Paris Paris while encouraging their children to pursue higher education and careers.

There are universities, art academies, open-air markets, and restaurants serving up authentic African cuisines. There is idyllic riverside scenery that draws visitors from the capital and abroad. New construction associated with the 2024 Paris Olympic games is transforming some neighbourhoods.

The ball is in Macron’s court, but I don’t know what he would have to say to change minds Sylvie Dufournaud, cafe owner

Sensing abandonment by central authorities, residents have learned to struggle to improve the quality of their own lives. Sylvie Dufournaud opened a cafe five years ago on a corner where both longstanding cafes had gone out of business, in an effort to counter creeping desolation.

“The most important thing is to maintain links between people,” she said. “And the way to do that is to go get them off their smartphones and WhatsApp and get them together to talk to each other.”

For her and others, the net effect of the policies of Ms Le Pen, who has advocated banning Muslims from wearing hijab in public and barring immigrants from reuniting with relatives in France, is perceived as not very different from that of Mr Macron.

Ms Dufournaud was perplexed as to how the president might change that perception by 24 April.

“The ball is in his court, but I don’t know what he would have to say to change minds,” she said.

A woman walks past a train track in Seine-Saint-Denis (Borzou Daragahi)

Many French fear Mr Macron still does not get how vulnerable he is to losing power, and are terrified that Ms Le Pen will win, which would have major implications for France, the EU and Nato. Ms Le Pen is friendly with Vladimir Putin, and allied with Donald Trump, Victor Orban and other western far-right figures.

She now insists she does not want to take France out of the EU, but has advocated a course that would effectively sabotage French adherence to European rules.

Ms Le Pen has also said she does not want to withdraw France from Nato, but advocates removing Paris from the alliance’s integrated command and working more closely with the Kremlin, even as Russia menaces the west with its unprovoked invasion of Ukraine.

She is polling at between 45 and 48.5 per cent of the electorate, putting her within striking distance of the presidency.

Marine Le Pen smiles during a campaign event in Gennevilliers, near Paris (AFP via Getty Images)

In 2017, Ms Le Pen won only a third of the vote, as leftists and minorities rallied around Mr Macron. Many analysts harbour doubts that the incumbent and his handlers understand his predicament.

“If he really wants to win, he needs to make compromises with this part of the population he has been ignoring or even targeting,” said Rim-Sarah Allouane, a Toulouse-based researcher on constitutional law and political commentator. “He needs to get rid of his most controversial ministers.”

Those officials include interior minister Gerald Darmanin, who once chastised Ms Le Pen in a debate for not being hard enough on Muslim immigrants.

Mr Macron’s path to alienating minority voters, which once had hopes for the youthful political upstart, began at the beginning of his term.

France has struggled to improve the lives of the people in the banlieues for decades, vowing to upgrade housing, public services, and transport links for underserved residents through various plans villes – or city plans.

A pedestrian walks past a poster reading ‘I vote = I decide’ in the Paris suburb of Ris-Orangis (AFP via Getty Images)

A former investment banker who is close to global financiers and consultants, Mr Macron all but abandoned such efforts.

“I’m not going to announce a plan ville or a plan banlieue,” he said in 2018. “This strategy is as old as I am.”

But instead of offering up new proposals, Mr Macron began hectoring the people of the banlieues for failing to live up to French standards, specifically targeting French Muslims after a series of terrorist attacks.

In a 2020 speech , Mr Macron criticised the “separatism” of Muslim communities and announced a bill that would supposedly bolster “republican patriotism” while at the same time acknowledging the failures of the state in providing adequate services and support for the communities.

But when it became law last year, the proposals to provide social benefits and protections had been stripped away, leaving only attempts to regulate the private lives of Muslim citizens.

“The separatism law created a real wedge between the community and Macron,” said Ms Khalfa. “When you stigmatise a population, you reinforce the tendency toward radicalism.”

Muslim worshippers pray at the Grande Mosquee de Pantin, northern Paris (AFP via Getty Images)

Mr Macron’s defenders point to the fact he has overseen the country through a turbulent few years. First came the gilets jaunes, the rightwing-influenced yellow vests movement that caused chaos on the streets and brought cities to a standstill. Next came the Covid-19 pandemic which struck France particularly hard.

A product of elite French institutions, Mr Macron is not known as particularly likeable, the quintessential pupil who sits in the front row and tattles on those who are misbehaving in the back of the classroom.

He has been accused of being arrogant, tone deaf and haughty, not just to the people of the banlieues and Muslims but also to other members of the French elite, including within his own government, and other segments of society.

Macron’s level of unpreparedness to face Le Pen in a few days is very, very worrying Pierre Jacquemain, political strategist

He once urged an unemployed gardener who approached him about his struggles to find work to get another job – at a hotel or a restaurant or wherever was hiring.

“I can find you a job just by crossing the street,” Mr Macron told him in 2018, in a moment that seemed to capture his personality and failings.

The president is now being accused of failing to recognise the severity and urgency of his predicament. Just last week, Mr Macron said he regretted not entering the presidential race sooner, citing his diplomacy over the war in Ukraine.

French political strategist Pierre Jacquemain called Mr Macron’s public appearances since the first round “distressingly flat” and “dormant”.

“This level of unpreparedness to face Le Pen in a few days is very, very worrying,” he wrote on Twitter. “Repeating ‘the far-right candidate’ will not be enough.”

Jean-Luc Melenchon (R) casts his ballot for the first round of France’s presidential election at a polling station in Marseille (AFP via Getty Images)

Mr Melenchon is a Moroccan-born son of parents with Spanish ancestry who moved to France when he was a boy, and may have the ability to connect with immigrant communities more naturally despite being 70 years old.

However, Ms Le Pen’s appeal to some minority voters is more complicated.

While her father was widely considered a dangerous neo-fascist, Ms Le Pen has spent a decade ditching his legacy and smoothing out and softening some of the rougher edges.

She even renamed her father’s National Front, the National Rally, and on social media fashioned herself a lover of cats. In interviews, she portrays herself as sensitive and humble.

Many of France’s newer voters might not even remember the toxicity of Jean-Marie Le Pen, who was booted from the party by his daughter in 2015.

“I’m not sure if young people have the same idea of history, of fascism,” said Ms Anquez, the deputy mayor of Ile Saint-Denis. “They grew up with the new, softer version of Marine Le Pen.”

Marine Le Pen poses for a picture with a supporter during a visit at a grain farm Soucy, Burgundy, 11 April (AFP via Getty Images)

At an Ivorian cafe serving generous heapings of yassa, spicy stewed chicken on rice, a customer finishing his lunch loudly declared that he would vote for Ms Le Pen.

“I am an immigrant and I am going to vote to end immigration,” he said.

Other diners laughed. No one reproached him.

Those who have tried to rally support for Mr Macron are pilloried. When the Syrian French photojournalist Ammar Abd Rabbo posted a call to arms against Ms Le Pen on Facebook, he was lambasted.

“What if we don’t want Macron either?” retorted one commentator, likening it to a choice between plague and cholera.

Mr Faya, the engineer, wondered whether some in his community were toying with a vote for Ms Le Pen at the last moment, just to break the cycle of being forced to choose between the lesser evil.

Polls suggest just a few thousand votes could sway the election in her favour.

“There seems no way of escaping this,” he said. “I have a 14-year-old son. I don’t want him to have the same kind of choice in the next elections. At least with Ms Le Pen, things will be clearer.”

Gert Van Langendonck contributed to this report.