PAK FORCED TO PAUSE ON AFGHAN BORDER FENCE

A red-faced Pakistan is having to tactically pause its stand on the border dispute with Afghanistan, even as it pleads with the world to rush humanitarian help to the beleaguered western neighbour.

The Taliban whose return to power it facilitated last year are unwilling to relent on the last 21 kilometer of a fence Pakistan is erecting to prevent illegal movement of humans, goods, drugs and weapons.

To the Taliban, allowing the fence would in principle mean acknowledging the border that successive Kabul regimes, including theirs (1996-2001) have opposed.

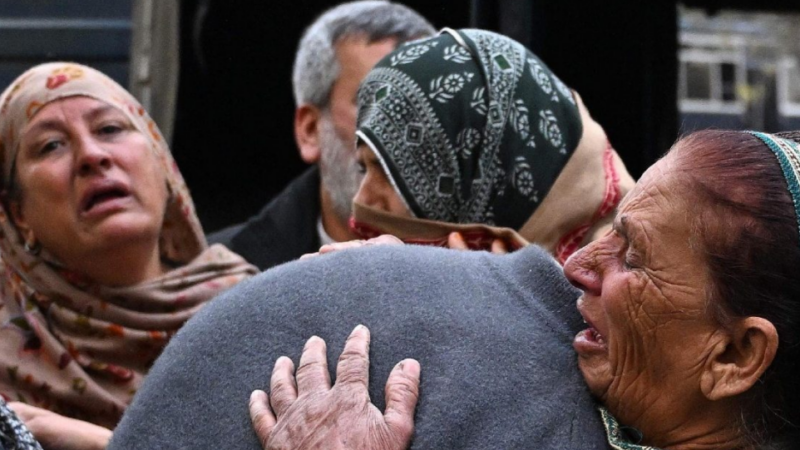

The Afghans say border, called the Durand Line, so named after the British officer who coerced the then ailing Amir of Afghanistan into signing in 1893, is a colonial era imposition. Culturally and emotionally, it runs through their idea of a ‘Pushunistan’, and divides the Pushtun tribal people through their families and homes.

With the Taliban barely four months in power and still struggling, the border in their Nangarhar province flared up with mortar fire last year-end. Taliban soldiers uprooted the fence and took away the barbed wire, threatening ‘war’ if the Pakistanis persisted. There were no casualties.

Over the past two weeks, videos have surfaced on social media purportedly showing Taliban fighters uprooting a portion of the fence along the Pak-Afghan border, claiming that the fencing had been erected inside Afghan territory.

However, in a more recent video being shared on Twitter, Afghan Defence Ministry spokesman Enayatullah Khwarzmi was seen saying that Pakistan had no right to fence the border and create a divide, adding that such a move was “inappropriate and against the law”.

Both sides have sought to play down the incident. After Kabul confirmed it, Pakistani Foreign Minister Shah Mahmood Qureshi on January 3 attributed the clash to “some miscreants.” The issue would be “resolved at diplomatic level,” he announced.

Now, the Afghans are quiet and the Pakistani leadership is talking in varying tones.

While Qureshi was taking a diplomatic stance, the Pakistani military talked tough. Inter-Services Public Relations (ISPR) Director General Maj Gen Babar Iftikhar on Jan 5 categorically said that fencing of the border would continue as planned, adding that the “blood of martyred soldiers” was involved in erecting it. His reference was about many Pakistani soldiers who have over the years died trying to protect the fence.

Diplomatic talks have not yielded any results. In a change of tone, a generally acerbic Pakistan Interior Minister Sheikh Rashid told media in Islamabad on January 14 that the remaining fencing of the Pak-Afghan border would be completed with the ‘consent’ of the neighbouring country, stating that “they are our brothers”.

Significantly, the Taliban, who operated from Pakistani territory for two decades before taking Kabul, want the fence to go. Taking advantage of a weak government in Kabul, and with a tacit nod from the United States that backed it, Pakistan had fenced most of the border despite protests from Kabul.

Minister Rashid’s stance indicates a tactical climb-down, although temporary, so as not to ruffle the feathers in Kabul. Any tough stance by the Taliban, analysts say, impacts Pakistan’s own credibility while it seeks to canvas support among the international community. On the other hand, it disturbs the good-neighbour stance it has adopted in the National Security Policy Prime Minister Imran Khan unveiled on January 14.