Terror, Trust Deficit Ignite 2 of Pak Frontiers

In double trouble for Pakistan, two of its disputed borders with Afghanistan and India respectively flared up recently, sending grave signals to its military-backed government that exporting terrorism would carry grave consequences.

Pakistani Rangers exchanged mortar fire with the Taliban guarding the Afghan border in eastern Nangarhar province after the latter ripped away the border fence being laid by the Pakistani personnel. The local Taliban official threatened ‘a war’ if the Pakistanis persisted.

The barbed wires were disassembled and sent to Afghanistan, according to the Afghan news outlet Khaama Press (KP). A video of the incident had gone viral, showing Afghan forces threatening their Pakistani counterparts with serious ramifications if the barbed wire was erected along the border again.

According to Khaama Press, Pakistani soldiers unleashed artillery in Kunar province following the incident in Nangarhar province’s Gushta area. This indicates that both sides have upped the ante along the disputed boundary.

The governments in both Kabul and Islamabad maintained diplomatic silence, letting the locals do the talking and acting.

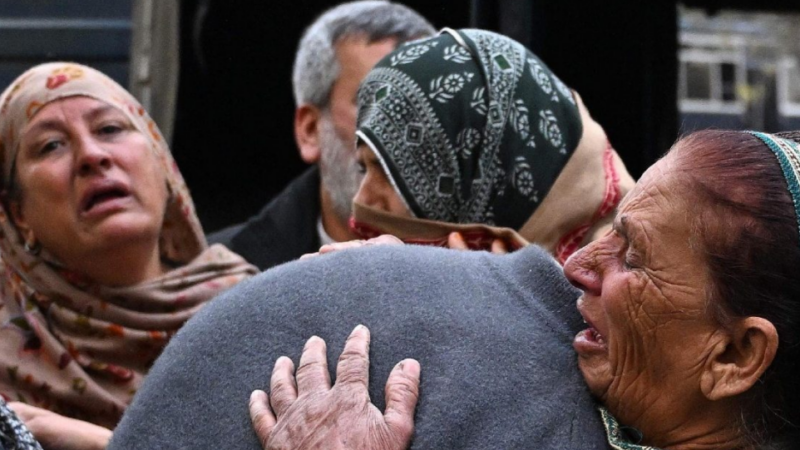

Around the same time this incident took place in the third week of December (2021), Pakistani personnel clashed on the border with India in Jammu and Kashmir when the Indians thwarted efforts to infiltrate militants.

The Indian Army had formally raised the issue of Pakistan Rangers starting a construction project just across the LoC, opposite Kupwara district in India’s Jammu and Kashmir union territory. Pakistan’s action apparently violated mutual agreements and understandings of maintaining a status quo on the de facto border unless the other side was informed in advance.

Pakistan Rangers who had begun constructing a structure on the other side of the LoC, but which was within 500 meters of the fence, immediately halted their work.

Here again, both Islamabad and New Delhi, generally prickly about border clashes, maintained stoic silence on an incident which is considered “too routine and too frequent” in diplomatic circles to lose sleep over.

But the two incidents carry disquieting portends for Pakistan that is obsessed with the Kashmir border dispute with India, and has sought to ‘normalise’ the border with successive governments in Afghanistan.

Islamabad invested heavily in the Taliban in the mid-1990s when the latter took power in Afghanistan and, again, after they were pushed out of power following the US-led invasion in 2001. Nearly two- decades’ sheltering and nurturing of the Taliban was meant to acquire “strategic depth” vis a vis the perennial enemy India. However, the Taliban’s return to power in Kabul in August 2021, from securing that ‘depth’, has denied it even the basic peace with Afghanistan. Although landlocked and dependent upon Pakistan for reaching out to the sea, the Afghans have doggedly refused to acknowledge the British-era defined border.

Pakistan does enjoy economic advantage over its western neighbour, profiting and at times, choking the border. But this has come with illegal movement of human, drugs and arms smuggling – both ways – and a safe haven for its wanted criminals and more significantly, the militants Islamabad nurtures as “state assets” who grow out to bite the hand that feeds them.

Created as a separate ‘homeland’ for the Muslims of the Indian Subcontinent, but as many historians say, as part of the British imperial design, Pakistan was born in 1947 with the twin border disputes. Its forces’ invasion of Jammu and Kashmir within two months of its birth ended in a stalemate and has remained the cause of four wars with India. Afghanistan sought to meet the new entity by being the only country to oppose Pakistan’s membership of the United Nations.

The intervening seven decades-plus, especially the last half-a- century, have seen Afghanistan moving from monarchy to regimes that have been violent and unstable. The intervention, first by the erstwhile Soviet Union (1979-90) and then by the United States (2001-2021), have devastated the country further but it has somehow

retained its territorial integrity.

What also remains unchanged is Kabul’s doggedness about recognising the Durand Line (named after the British official who drew it in 1883). The reason for this is clear, but has been overlooked by the big powers and the stake-holders in Afghanistan. The arbitrarily drawn line – that began on a map and a red pen and formalised on the ground later to Kabul’s disadvantage – cuts through the heart of the Pashtun populace, sowing seeds of mistrust and hatred and divided political loyalties between two adversarial regimes.

The Afghanistan-Pakistan border clashes began in 1949 and have recurred from time to time with varying intensity. They did not change with Pakistan’s playing the proxy for the Western powers against the Soviet Union and with its double game of fighting terror alongside the West and nurturing the Taliban at the same time in the last two decades.

Given the Afghan desire to reunite the Pashtuns, analysts say, they are unlikely to change now when Pakistan is aligned with China that hopes to extend its economic footprint into Afghanistan by either a parallel effort or to extend the China Pakistan Economic Corridor (CPEC).

Experts aver that the Chinese outreach across the Durand Line may be problematic just as the CPEC itself faces local resistance through Pakistan’s tribal Khyber Pakhtunkhwa and in Balochistan where the Gwadar port that provides China the entry to the Indian Ocean and the Gulf is located.

Puzzling or ironic it may seem, the Durand Line in the mountains may prove a bulwark against China’s maritime ambitions, thanks mainly to its partnership with Pakistan that has failed to deal with its neighbours on one hand and on the other, its own volatile population.

Perhaps, Durand did not foresee the advent of China as an economic juggernaut reaching the warm waters of the Indian Ocean, something his imperial masters wanted to deny the Czar of Russia and the Soviets.