New born paying the price of Taliban in competence to bring foreign aid in nation

Kabul, Afghanistan: In absence of the foreign aid in Afghanistan and all the humanitarian crisis which Taliban is not able to solve, the new born children are paying its price as most of the children born are malnourished and weak.

Wrapped in thin blankets, Nafisa struggles to open her fluttering eyes. She is only five months old but carries the air of an old woman – her pink skin cracked and stretched around her painfully gaunt frame.

“She has lost her appetite. She lacks blood,” her young mother, Nafisa, tells me gently from beside her small cradle. “It has been six days here.”

Doctor Ahmadullah examines her chart and pulls his shoulders back, putting on a brave face in a job that seems wincingly never-ending.

“Nafisa has swelling, edema, her stomach is upset, and her muscle is wasting,” he says wearily. “She is five months old, but she looks a year old. Children (with malnutrition) age very fast.”

Only baby Nafisa is hardly alone in her fight for survival inside the fading, rundown walls of Kabul’s Indira Gandhi Children’s Hospital. Three wards of the state-run facility overflow with the desperately ill and the needy. Two or three infants share a cot or incubator bed given the lack of room, and weary, helpless mothers stoically breastfeed on the floor.

“There is no medicine. There is no food. There is no salary,” laments Dr. Noorulhaq Yousufzai, Associate Professor of Pediatrics, who has worked at the Indira Gandhi Children’s Hospital for 28 years. “We have 360 beds, but we have more than 500 patients a day. And if we do not have the right medicine, a child will die.”

The hospital typically treats newborns to those aged around 14. A large portion of those admitted suffers from severe malnutrition.

“The malnutrition patients are increasing, and now we see many more with measles because the vaccination programs have deteriorated. But the biggest predisposing factor of all this is poverty,” Yousufzai explains. “If you are not getting enough food, your immune system will weaken. And the economy is only getting worse, and this is hurting the children.”

While Afghanistan’s government healthcare system has long been in dire straits – held afloat almost entirely by the flow of foreign aid for the past two decades – that band-aid was ripped from the bullet wound three months ago amid the swift Taliban takeover. The U.S. subsequently froze $9.5 billion in aid, as did the International Monetary Fund (IMF) and World Bank.

Most humanitarian assistance has not returned, and the economy is rearing toward collapse. The United Nations estimates that 8.7 million people in the war-ravaged nation live in near-famine circumstances. Some 24 million – sixty percent – endure acute hunger, and 95 percent of the 38 million do not have enough to eat. Some 3.2 million children under the age of five are said to be suffering severe malnutrition.

“There is no medicine. So I paid for the medicine and injections from the outside,” one tired mother Shakiba, with crescent moons of darkness below her eyes, says sadly of her seven-day-old daughter with jaundice, who is yet to be named and referred to as the child of Abdul Jabar.

Dr. Humayoon explains that the only stock they can carry is to treat “a common cold” for the very first steps of recovery.

“After that, we don’t have,” he says. “We have basic necessities. Beyond that, the patient has to pay.”

Meanwhile, stick, discolored limbs jut from 18-month-old Mariam’s diminutive dress as her Aunt Aminia watches over. Blonde wisps fall over her ancient little face as she endeavors to open expressionless eyes.

“She has wasted blood and so malnourished that her hair has lost its color,” Dr. Ahmadullah asserts. “Causes of malnutrition include the mother, who doesn’t have good health and lacks the necessary vitamins. This is due to low income, difficulty obtaining food, and various physical and mental health conditions.”

Many healthcare facilities once operated by international donors have all but disappeared since the regime change, putting an even more onus on the shattered public system. In addition, life-saving medical supplies have all but dried up, with little to nothing coming in.

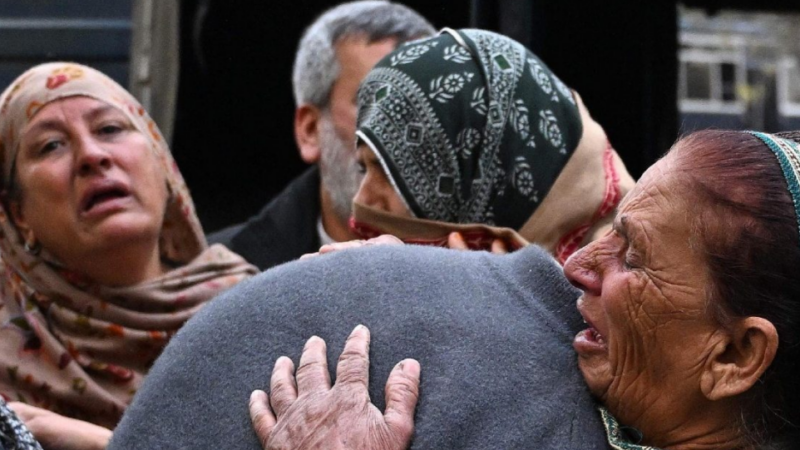

It is harrowing to watch tiny Meena, two and half years old, peer out lethargically at the world, her eyes beetling from an ashen face. Meena’s mother died more than a year ago, and her grandmother Bibi Hanifa holds her frail hand.

“She is gaining some weight, so today she will be discharged,” Dr. Humayoon says. “She is still behind average weight, but we don’t have enough space.”

Then there are cases like Hidayatullah. Circumcision was performed on the eight-month-old two weeks earlier, but he contracted an infection. As a result, giant swaths of raw, red blotches envelope his entire body as he battles to cry out in agony. Moreover, Mansoor, at just 20 days old, has jaundice and presumed cerebral palsy.

“There is no treatment for it,” a trainee physician, Dr. Muslim, notes. “The brain might start working, and he might start eating, but some parts of the body will never develop.”

Around three percent of the children admitted over the past three months – approximately 90 per month – have died. Malnourished patients are increasing by the day and are categorized in three wards starting with the most severe, to the slightly improved, and then to the stabilized.

Hadia, 35 days old, was diagnosed with having holes in their hearts and veins “not working properly,” of which the medical professionals tell me there is no cure. And Huma, the mother of five-day-old Zainab, says she knew something was wrong when her daughter did not cry after the birth.

“The situation is not good,” Dr. Humayoon admits quietly. “She cannot receive oxygen normally. Her brain has not received enough oxygen, and she cannot take the milk.”

Another small boy in a cot nearby has been diagnosed with a congenital heart condition.

“We cannot do anything here. Not just in our hospital but all of Afghanistan. These kinds of patients must go to Pakistan or somewhere else because they require surgery. It is not a simple procedure.”

When I ask what happens – given that most families who come to Indira Gandhi are far below the poverty line – in situations where they cannot scramble the funds for the journey, Dr. Humayoon looks at me solemnly.

“This is a big problem for him,” he responds. “He must go.”

There is also a ward for extremely premature babies – usually born at least two months early – fighting for life.

Afghanistan now faces a war of a different kind.

“There aren’t as many patients now with bullet wounds and (war injuries), but we also have many surgical cases like road accidents and children falling from roofs,” Yousufazi explains. “But its winter season, so the number of respiratory infections and pneumonia are becoming very high, as well as viral diseases like measles, mumps and meningitis.”

While the burden of care almost always falls to the mother, Nazar din is a rare father nursing his eight-month-old, malnourished daughter Aseya in a narrow room flecked with sunlight from the decaying curtains strewn across the window.

“She was not drinking milk, and we were afraid if she would survive,” Nazar tells me flatly. “She was 3.5 kg (7.7 pounds), and now she is 6kg (13.2 pounds).”

Still, he works as a daily laborer, and there are barely any jobs available. He worries about how he will feed his six children.

“There is no business around, yet we must provide for the family and don’t have other options be it by loan or something else,” Nazar continues. “We must provide, but since the new government, we don’t have any work at all.”

Making matters worse is the notion that healthcare workers have not been paid in months and did not receive salaries under the final months of the now-defunct Ashraf Ghani-led government, let alone under the cash-strapped Taliban. At one point during our visit, female nurses timidly confront us in the hallways, begging for someone to pay their salaries.

“We are government employees, and the staff is making money only from the idea of making money,” Yousufzai continues. “Our workers don’t even have money to pay for transportation, and often they are coming to work from very far places. There is no money for taxis and buses.”

The workers now effectively work for the Taliban regime, which essentially targeted them during their years of bloody insurgency.

In late February 2010, a Taliban attack struck foreign guesthouses and killed sixteen – nine were doctors on missions to serve the impoverished Indira Gandhi Children’s Hospital.

Built with Indian aid money during the Soviet occupation in 1985, the state facility has long strained to keep up with demand – often having to turn patients away.

“At the time it started, it was a dark time. There was a Civil War, and the hospital was the frontline,” Yousufzai recalls. “I was on duty one night, and I remember a rocket was launched right into the hospital. After that, we lived in tents until it was renovated because the infrastructure was destroyed.”

Some say the hospital itself is also victim to the systemic corruption that has hamstrung Afghanistan during the years of U.S footprint and flush of foreign monies, with workers stealing supplies to sell to local pharmacies.

Nevertheless, the young and innocent always bear the brunt of the unfurling crisis surrounding them.

In addition to the financial catastrophe, a pariah government, mass displacement from conflict and years of punishing drought pushing many more to the threshold of famine, winter has settled across the blood-splattered land.

“We don’t have a salary, and that is the situation. Many aren’t working at all because the government collapsed,” adds Humayoon. “But we continue to do this because it is our responsibility. We should save the lives of the people. This is the responsibility of every doctor, and we will fight because this is our country. These are our people.”