I’ve watched US policy pave the way for the terror attack in Kabul

There were sudden shouts of “Get down… keep down”. A suspected bomber had been spotted in the crowd. “It’s a male in a white dish dash, a red cap and a blue bag”, was the warning shouted by the British soldiers to the Americans and other foreign troops further up the road.

“He’s among us”, shouted another soldier as we crouched down on the ground. An American ran over with Electronic Counter Measure (ECM) equipment in case the explosive device was designed to be triggered by a telephone call. Taliban fighters, who were standing yards away, started to back off, a few crouched down and a few whipped out their mobiles, to the alarm of the western troops.

The suspect was not found despite a search. There were other things to worry about as well; four people, all women, had been killed that morning in the crush of the crowd. Their shrouded bodies lay on the side of the road, their families huddled around weeping in grief. Three more people were to die in the course of the day.

That alert was on the same road, the first of several, outside the British base in Kabul, where the bombing took place on Thursday, killing at least 80 Afghans and 13 US troops.

The plan was simple and lethal, explosions near either end of a narrow walled corridor, hemming people in with no chance of escape. That was an obvious means of causing carnage, we would say to ourselves, as we left The Baron hotel on to that road to report on the evacuation with thousands of people, desperate and scared, trying to reach the airport.

We knew that there was absolutely no way that British troops, who would be the first to meet the crowd, would be able to search everyone. The same constraint applied to the Taliban checkpoint further up the road.

We debated on whether the Taliban would want such an attack to take place. After all, they had what they wanted, the country, the crushing of their opponents and the withdrawal of foreign troops. Why would they want to jeopardise it all by targeting the US?

On the other hand, could they control Isis and al-Qaeda? Those groups had focused their slaughter on Afghans and not western troops since the Doha Agreement had been signed between the Taliban and the Americans in February 2020, indicating a degree of collusion.

The Islamic State Khorasan, or Isis-K, has claimed credit for the bombings. It is not the first time it had carried out mass murder of Afghans; 85 people, mostly students, were killed in an attack on a girls’ school in Kabul three months ago. Another attack on a maternity hospital killed 24, including mothers and newborn babies. But the victims were Afghans and these deaths did not get that much publicity in the west.

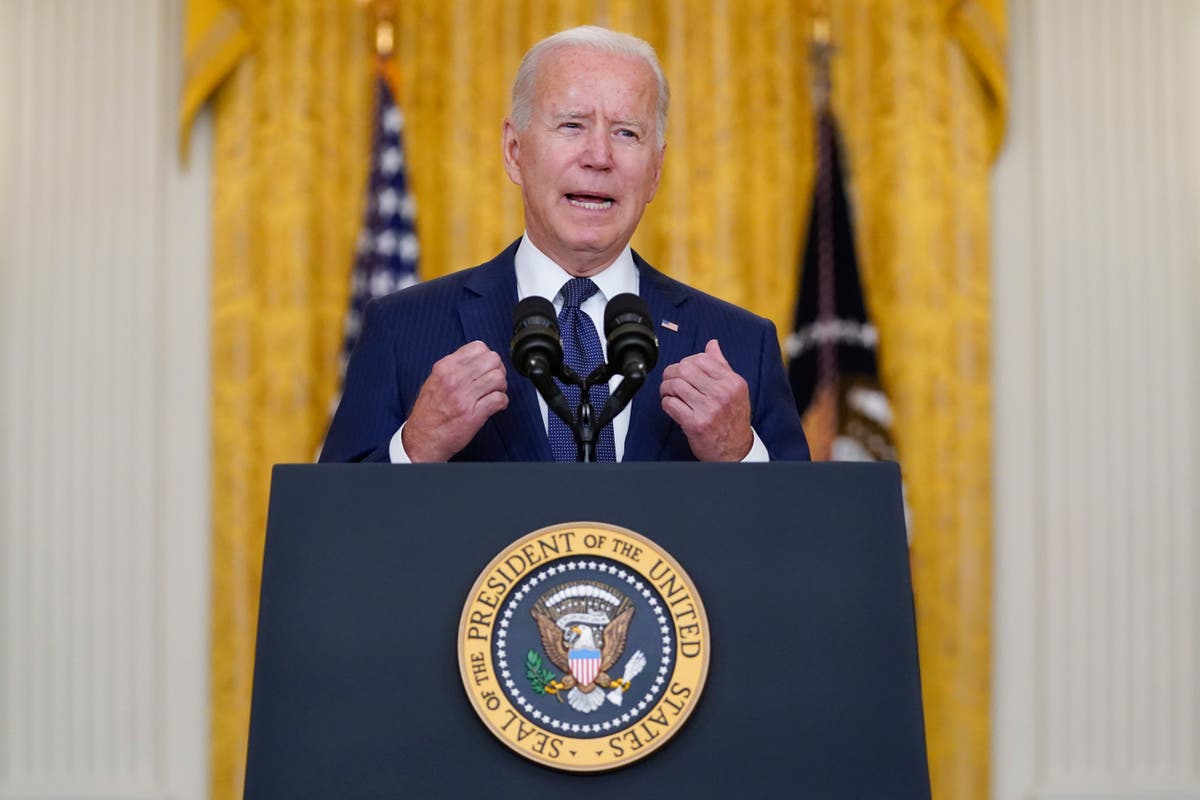

What happened on Thursday has resulted in the largest number of US deaths in one day during America’s longest war since 30 service members were killed when a helicopter went down in 2011. And Joe Biden’s administration bears a huge amount of responsibility for that. It had put the members of the forces in a chaotic evacuation process which left them vulnerable to terrorist strike.

The decision of the US president to retreat at such haste from Afghanistan, the failure to start the evacuation much earlier despite repeated pleas to do so from NGOs and others, the refusal to extend the withdrawal timeline, all put American and allied troops in harm’s way.

It need not have happened. The war need not have ended so humiliatingly for the US, and so painfully for the Afghans.

The security presence for the last six years – around 2,400 Americans, just under a thousand from Nato, and 750 from the UK – was an insurance against the insurgents and the elements of the Pakistani military and their intelligence services, ISI, who fed and watered them.

This was thrown away by the Trump administration at the ineptly handled talks in Qatar led by Zalmay Khalilzad, resulting in the deeply flawed Doha Agreement which gave the Taliban almost everything they demanded.

Biden is now busy claiming that they inherited the bad deal from Donald Trump. But throughout the US presidential campaign he had repeatedly affirmed that he would not reverse the pullout decision. He had done nothing since getting to the White House about the repeated breaches of the agreement by the Taliban, which would have allowed the US to review its own position.

Other security decisions by his predecessor have been reversed by the Biden administration. For instance, it halted an order by Trump to withdraw more than a quarter of the US military forces, around 12,000 troops, from Germany. Trump had described his decision as punishment for Germany’s low spending on defence. It was widely seen to be an expression of his anger towards the German chancellor, Angela Merkel, who had repeatedly challenged him on a number of issues.

But then Biden had been strongly against the Afghan war while he was Barack Obama’s vice president and had argued, unsuccessfully at the time, over the surges of troops requested by the commanders. Biden had also, quite rightly, become a trenchant critic of the endemic corruption among the Afghan hierarchy, upbraiding President Hamid Karzai about it during visits to Kabul.

Ending involvement in Afghanistan had become Biden’s war and he was determined to end it as quickly as possible, seemingly impervious to the consequences of that. The timing of the pullout of the troops kept changing, adding to the confusion and anxiety among Afghans. It was at first, symbolically, to be on 9/11; then we were told almost troops would be out by 19 August, and then 31 August.

The pullouts often took place at night, including the one from Bagram, the centre of western military operations, without telling the Afghan government. This sapped confidence among the Afghan military, made the civilian population even more fearful, and buoyed the Taliban.

What has unfolded hardly lives up to Biden’s pledge on Afghanistan last year: “We will not conduct a hasty rush to exit, we’ll do it responsibly, deliberately and safely. And we will do it with full cooperation with our allies and partners.”

The collapse of the Afghan security forces has been truly spectacular; having covered quite a few missions with them, in which they have fought bravely and professionally, I was as surprised as anyone else by what transpired. Especially after seeing some of the units initially acquit themselves well in Herat.

What went so wrong will, no doubt, be examined in detail in the future. Biden put the blame for what had happened on the Afghan leaders and the military, and maintained that nation-building should never have been attempted by America, the US should have just focused on smiting terrorists and moved on. The Afghan mission should have ended after Osama bin Laden was killed – a strange argument, considering that the al-Qaeda leader was killed in Pakistan and not Afghanistan.

Biden, like Trump, has been called a Vietnam draft dodger. His criticism of the Afghan military, whose rates of deaths and injuries in combat are far higher than western forces, angered members of both American and British forces in Afghanistan. “I really didn’t like the way Trump would demean our military”, a US marine officer told me. “I didn’t like the way Biden talked about the Aghan forces. Many of us here now had fought alongside them over the years, we knew the sacrifices they made. We knew how much pressure they were under, we knew of the threats their families face.”

Having pulled out the troops, Biden sent twice as many to carry out an evacuation which was turbulent from the start, something which was bound to be the case with the time limits and terms of reference imposed.

To enable the airlift to take place, the US had to depend on the Taliban. The more troublesome and delayed the process got, the more the leverage of the Taliban grew.

While all this was going on, one argument put out repeatedly by American and other western officials was that the Taliban would ensure that the extremist groups would not disrupt the airlift through violence.

There was regular liaison between US and UK forces and the Taliban both at high and local level. William Burns, the CIA director, held confidential talks with the Taliban leader, Mullah Abdul Ghani Baradar, earlier this week over the evacuation and security issues. American and British officers hold regular talks with the Taliban: the building next to The Baron hotel had been occupied by the Taliban seemingly without problems.

At the end, as we now know, that belief on the Taliban ensuring security was misplaced, and the bloodbath that unfolded has raised important questions about what happens next.

The Taliban and Isis are linked through the Haqqani network which has strong connections with the Pakistani intelligence service, ISI, and al-Qaeda.

The overlapping interests of these groups had meant that despite Isis’s disparagement of the Taliban as not being true jihadists, there has not been open warfare between them and the Talibs who, as hosts in the country, had a measure of control.

That now appears to have gone, helped, perhaps by Isis augmenting its numbers when the Taliban threw open prisons in every major city they captured. An alternative scenario is that there are hardliners among the Taliban who will go their own way, whatever the broader strategic objective of the leadership.

All this points towards grim repercussions for what Biden had done. The west has, of course, walked away from Afghanistan before, after using the mujahideen against the Russians. We know what happened then, the creation of ungoverned space, terrorist camps, al-Qaeda and 9/11.

At a 4 July press conference at the White House Joe Biden complained when asked about Taliban advances in Afghanistan. “I want to talk about happy things, man.” The US president may well find that abandoning Afghanistan does not actually take him to a happy place for long.