British troops leave Afghanistan amid warnings ‘very bad things’ could happen to country

The government has formally announced that British forces have finished their mission in Afghanistan ending, along with other international troops, the involvement in a long and contentious war which has divided opinion home and abroad.

But the departure comes as Afghanistan faces an uncertain and dangerous future with lethal onslaughts by insurgents taking a rising daily toll of lives, and deep trepidation about the future, especially over the hard-won rights of women, if the Taliban take over once again.

The haste with which the withdrawal has been carried out and the deteriorating security situation in Afghanistan has raised deep concern about possible consequences in the region and beyond.

General Lord Richards of Herstmonceux, the former head of the British military who commanded the International Security Assistance Force in Afghanistan, warned of dangerous times ahead. He could not, he said, see any coherent western strategy to counter what is likely to unfold.

Lord Richards told The Independent: “This is a hugely important and worrying time. We have a moral obligation to the Afghan people, but leaving that aside, one needs to look cold bloodedly at the security situation.

Recommended Massive meteor lights up night sky in Florida

“A security vacuum, an ungoverned space, will allow some very bad people to plot some very bad things. We should all remember that the intervention in 2001 took place because the 9/11 atrocity was conceived in an anarchic violent Afghanistan.

“I do not want to be entirely pessimistic. There is a possibility that with the right balance of financial carrot and punitive stick the Taliban may join in the political process and we may be able to avoid prolonged bloodshed.

“But this requires robust and dynamic western support. I see no coherent plan to this effect. Without it, I am not hopeful. We shall have to see what happens.”

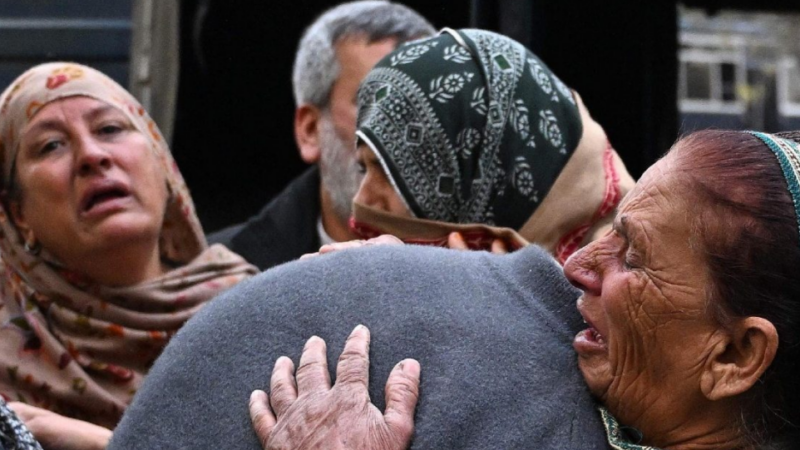

An Afghan civilian carry a wounded child to the hospital after he was injured during fighting between Taliban and government in Badghis province, northwest of Afghanistan (AP)

General Sir Nick Carter, the Chief of Defence Staff, acknowledged that the insurgency was rapidly gaining ground.

“The starting point is that recent news from Afghanistan has, of course, been pretty grim … I think it’s fair to say that the Taliban now hold nearly 50 per cent of the rural districts of Afghanistan,” he said.

The worst case scenario, General Carter continued, “is that Afghanistan fractures. You see a sort of cultural warlordism, and you might see some of the important institutions like the security forces fracture along ethnic or tribal lines. If that happens, I guess the Taliban would control part of the country.”

However, General Carter, who had served extensively in Afghanistan, wanted to stress that government forces were concentrating in protecting urban centres, where the majority of the population now live, and also that none of the provincial capitals have yet fallen.

General Carter maintained that a viable scenario would be the Taliban would be forced to come to a deal with the Afghan government at the end of an attritional conflict.

“It is entirely possible that the Afghan government defeats the Taliban for long enough for them to realise that provincial capitals will not fall, that they can’t achieve the outcome they want militarily, and want to talk.”

Announcing the pull-out to the House of Commons, the prime minister, Boris Johnson, pointed out that western intervention in Afghanistan took place after the country, under the Taliban, had become a base for Al-Qaeda to carry out international terrorism including the 9/11 attacks.

“The situation [now] is very different, the training camps have been destroyed, what remains of Al-Qaeda leadership no longer resides in Afghanistan and no terrorist attacks against western forces have been mounted from Afghan soil since 2001,” he said.

Smoke rises from fuel tankers at the Islam Qala border with Iran, in Herat Province, west of Kabul, Afghanistan. Taliban have taken control of Islam Qala crossing border in western Herat province (AP)

Mr Johnson pointed out that “virtually no girls attended school” in Afghanistan “under the Taliban, who as a matter of policy had driven them from the classroom and forbidden them from returning … Today, more than 3.6 million girls are going to school in Afghanistan … Today, women hold over a quarter of the seats in parliament.”

The UK will continue to support the Afghan government, he said, pointing to £100m which had been allocated in development aid and £58m for Afghan armed forces.

However, the main reason why Afghanistan had been relatively free from turning once again into terrorist plotting ground has been the presence of international forces supporting the government against the Taliban and other Islamist groups.

Many areas of Afghanistan that the Taliban had captured recently had seen schools for girls shut down: the US administration is considering issuing a system of visas for women in public life such is the worry about the dangers they are likely to face.

For former commanders such as General Sir Richard Barrons, the west had run out of options in Afghanistan. The former chief of Joint Forces Command, who had served in Afghanistan and Iraq, held that what had happened was inevitable.

“The start of every year there was a cycle of optimism over the gains made and a hope that during the course of that year there would be changes, the Afghan government will become less corrupt and more efficient, the ANSF (Afghan National Security Forces) will be more effective and the insurgents will be squeezed in their bases in Pakistan, unfortunately those hopes did not materialise”, he said to The Independent.

“A huge amount of blood and treasure was spent in Afghanistan. At the end it became clear that t was not in the national interest of the international powers to keep investing this blood and treasure. We will now have to wait and see what happens. It’s possible that there will be some kind of power sharing agreement with the Talban. And it is to be hoped that the Taliban will see that it will be to their advantage not to ally themselves with Al-Qaeda and Isis.”

But many Afghans do not intend to wait to find out whether the insurgency can transform itself into a viable political structure. Abdul Razak Wardak left the Afghan army after a decade of service in 2018 with the rank of captain to find another life in Kabul away from the conflict.

“When the talks [in Doha] started there was a lot of relief that may be an end to the war. My grandfather fought, my father fought and I had to fight,” said 36-year-old Mr Wardak. “I really hoped my sons won’t have to follow our paths.

“The only way I can be sure now that my sons can have a life away from war is to move my family out of the country. My brothers and I have to then decide what to do with the business we run. If we stay behind here, the war will come to us soon.

“The way our allies left this county, rushing out, was a signal for the Taliban to step up their attacks. How else will the Talibs look at it? They will try to take this chance and there will be a lot of bloodshed.”

A small number of UK forces will stay behind as part of an international contingent to guard the embassies remaining open in Kabul. They may also be on duty alongside American and Turkish soldiers to keep the capital’s airport running. Detachments of western special forces – American, British and French – could also be deployed, although details for this are yet to be finalised.

Western air support for Afghan forces, which had been a crucial factor in operations against insurgency, will be halted with bases shut down. However, a senior British officer reiterated on Thursday that “over the horizon” strikes by warplanes, stationed in neighbouring countries, could continue.

There was no great farewell ceremony at the end as British forces left. The last lowering of the Union Flag took place on 24 June behind walls at the airport by soldiers of the 3rd Battalion, Royal Regiment of Scotland in the presence of General Scott Miller, the US head of international forces in the country.

An Afghan National Army soldier stands guard at the check post at Mahipar, on Jalalabad-Kabul highway (REUTERS)

Defence officials denied that the secrecy was to avoid adverse publicity, insisting instead that it was to prevent insurgent attacks on departing troops.

Britain’s latest Afghan war, the fourth involving the country since the first in 1839, has ended after 19 years, eight months and six days. Although the reason for the invasion, following the 9/11 attacks , was in 2001, the war really started for the UK in 2006 with the deployment to Helmand. Until then, five members of the forces had been killed in total, three from suicide, accidental firearms discharge and a homicide respectively.

The Helmand mission, which the then defence secretary John Reid said hoped would finish in two years without a shot being fired in anger, resulted in a death toll of 457 UK soldiers and civilians. In total 150,610 service personnel served in Afghanistan over the years, around 8 million rounds were fired in combat, with the cost of the mission estimated to be over £40bn.

More than 2,320 US personnel have been killed in the conflict. The financial cost to Washington of Afghan operations, military and civil, has been a staggering £2.26 trillion with the money spent on war-fighting totalling $815.7bn.