The bodies of Muammar Gaddafi and his son Mutassim lay in a meat warehouse in Misrata. The eyes were shut in seeming repose, but the shrouds of white cloth thrown over them did not hide the wounds inflicted. A queue of people, young and old, men and women, families with babies, shuffled along the room, staring down at the corpses, whispering among themselves.

Gaddafi and his son had been hunted down, captured, tortured, and killed, as they tried to escape from their last place of hiding, their hometown of Sirte. The fate of the man who had ruled Libya for 42 years at the end of what was, at the time, the most violent revolution of the Arab Spring, was seen as an end to the old order and the beginning of a democratic future in Libya and the wider region.

In reality, however, the heady, intoxicating dreams of the revolutions were already dissipating. A month before Gaddafi’s death in October 2011, I had revisited Tunisia and the town of Sidi Bouzid. This was where a 26-year-old street trader, Mohamed Bouazizi, had committed suicide in protest at mistreatment in the hands of local officials, with a public slap from a female municipal worker the final humiliation.

Bouzazi’s terrible end, by self-immolation, was the act of despair which started Tunisia’s uprising, the flight of dictator Zine El Abidine Ben Ali after four decades in power, and the beginning, goes the narrative, of what became the Arab Spring.

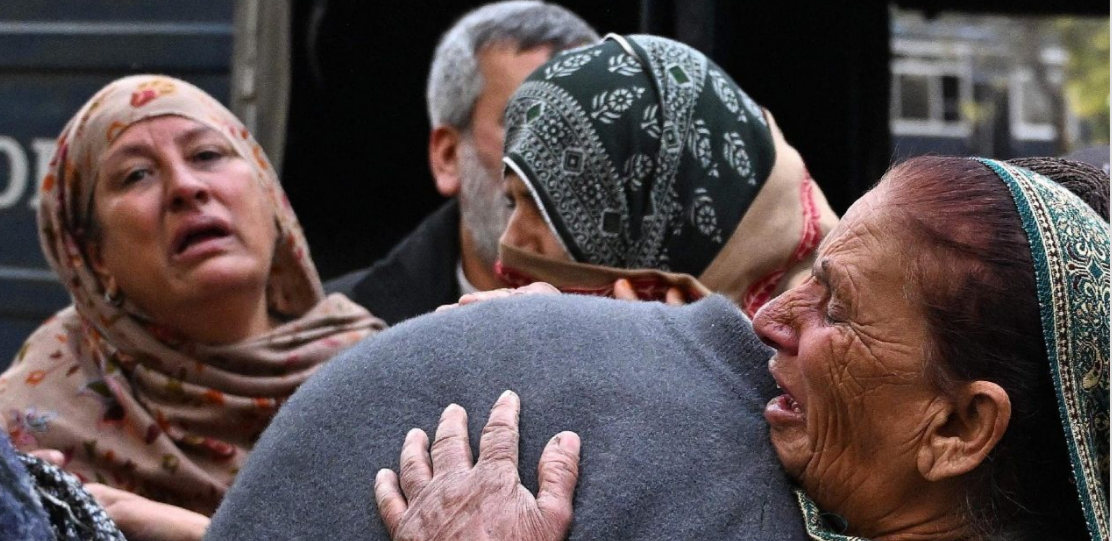

At the time, residents of Sidi Bouzid exulted in their status as the cradle of the revolution: they chanted Bouazizi’s name and put up murals dedicated to him. His mother, Mannoubia, told me: “We are poor and oppressed and my son protested and they drove him to death. My son has gone, but I am proud of what he did. Look how he has inspired the people all over the country.”

Mohamed Bouazizi’s fame rapidly spread far beyond Tunisia. He was selected by the European Parliament as a nominee for the Sakharov Prize, awarded to those who had played a pivotal role in bringing freedom to their country. In Paris, Mohammed Bouazizi Square was named in the 14th Arrondissement by the city’s mayor, with his mother, and one of his sisters, as guests of honour.

Eight months on, I found deep doubts among many about the course of the Jasmine Revolution and the story of Mohamed Bouazizi was mired in accusations and recriminations. His family had left Sidi Bouzid amid animosity from neighbours, who claimed they had been making money out of the death. A plaque put up in his name in the town has disappeared and slogans praising him painted over.

Please enter your email address Please enter a valid email address Please enter a valid email address SIGN UP Thanks for signing up to the The View from Westminster newsletter {{#verifyErrors}} {{message}} {{/verifyErrors}} {{^verifyErrors}} {{message}} {{/verifyErrors}} The Independent would like to keep you informed about offers, events and updates by email, please tick the box if you would like to be contacted

Read our full mailing list consent terms here The Independent would like to keep you informed about offers, events and updates by email, please tick the box if you would like to be contacted

Read our full mailing list consent terms here

The municipal official allegedly responsible for “the slap which rang around the world”, Fedya Hamdi, had been freed from prison, with all charges dropped, to cheers from a crowd gathered outside the courtroom.

Manoubia Bouazizi and her six remaining children had moved to the seaside at La Marsa, a suburb of Tunis where they lived in a medium-sized apartment. “I know some people are telling lies about us,” said Manoubia. “When he died, people came to me and said it was not just me who had lost a son, the whole village has lost a son. Now they say things against us. It is really bad.”

In Sidi Bouzid, the complaints spread beyond the city and the country to what was happening with the Arab Spring. “We started the revolution which led to all the others. But all we got in return were a few pats on the head from Europe and America,” said Ziad Ali Karimi, an activist. “Look at all the money they spent on Libya, because of oil contracts; here, we get nothing. The economic situation just gets worse, and we wonder why we risked so much in rising up against Ben Ali and his gangsters, and we did this without foreign help.”

The Libyan opposition also tried to do it without foreign help, at first. When the revolution had started, there had been posters proclaiming: “No foreign intervention, Libyans can do it alone.” It soon became clear that they could not, with the tipping point the attack by regime forces on Benghazi.

I was in Benghazi on that drizzly Saturday when Gaddafi’s tanks rolled into the city, past shattered homes and charred cars. The palpable fear was of retribution against those who had dared to rise up. Some had managed to escape, but many were trapped, expecting the worst. Mashala, my translator and friend, who had several activist brothers, said simply: “He will kill us all’.

The regime’s forces could have taken the city that day, albeit with a lot of bloodshed. The resistance was brave but in retreat. Yet the army commanders chose to pull back and relaunch the assault the following day with reinforcements.

It proved to be a fatal mistake. The air strikes, by the French and British, began that night. We saw the terrible result the next morning – a scene of desolation on a field edged with wildflowers whose prettiness jarred with the bloodshed. Gaddafi’s forces had been caught without cover; before us was a ghastly miniature of the carnage that had been wreaked on the road to Basra in 1991 when American and British warplanes had bombed Saddam Hussein’s forces as they retreated from Kuwait. All around us was an open-air charnel house of twisted smoking metal and charred bodies, of men incinerated with no chance of escape.

It took months of Nato bombing for the regime to fall. In that time, dozens of rebel groups sprung up, some of them supported with guns and money by wealthy sponsoring states in the Middle East, some with extremist Islamist links, all determined to fight for their division of the spoils.

We met Libyan expatriates who had returned to fight against Gaddafi. One of these occasions was with an American journalist in the western city of Sabratha, which had fallen to the rebels. After a while, there was a plaintive plea from my American colleague: “Hey, do you think there’s any chance at all to speak to someone who is not from Manchester?”

The British connection was strong, with some of the returnees members of the Libyan Islamist Fighting Group (LIFG), who had fled to the UK during the Gaddafi era.

Six years on, one of them, 22-year-old suicide bomber Salman Abedi, killed 22 people and injured more than 800 others at a concert in the Manchester Arena. Abedi, it emerged, had been influenced by people associated with the LIFG.

Problems were compounded by the fact that the west effectively abandoned Libya after the fall of the regime. The American withdrawal was hastened by the murder of ambassador Chris Stevens and three others in Benghazi by Islamists, believed to be Ansar al-Sharia, which was linked to al-Qaeda in Maghreb. The British pulled out after an ambush soon afterwards on a convoy carrying the ambassador.

But now foreign powers are back in Libya in force. The Russian private military company, the Wagner Group, is there, fighting alongside General Khalifa Haftar’s Libyan National Army (LNA). As well as Moscow, the former commander in Gaddafi’s army is backed by the UAE, Egypt and France. His main adversaries, the UN-recognised Government of National Accord (GNA), has the support of Italy and Turkey.

This foreign influence has been present in most arenas of the Arab Spring. The Syrians sent to Libya are drawn from Turkish controlled militias in the country where Vladimir Putin’s military intervention ensured that Bashar al-Assad survived, just as Nato’s campaign in Libya was instrumental in Gaddafi’s fall.

The Libyan revolutionaries had also sought to gain their victory by themselves. They wanted western arms, but without strings attached. I spent six weeks in Aleppo in the summer of 2012, as they battled to take Syria’s largest and richest city, and came close to doing so. The rebel forces, however, were never united, and the arms they got from across the Turkish border was nothing like enough in quantity to overcome regime armour.

But one group seemed far better supplied than the others. Jabhat al-Nusra, allied to al-Qaeda, came with significant weaponry and shiny 4×4 vehicles to drive around in with funding from Gulf states. They were hostile towards journalists, as well as other rebels. They did not, however, show much fighting prowess. On one occasion, for example, they fled, throwing away weapons, as regime tanks came through the frontline at Salheddine. The chaotic retreat caused much mirth among fellow fighters.

Al-Nusra soon ceased to be a laughing matter. They grew rapidly in size with an increasingly large contingent of foreign fighters and a steady delivery of weapons. Returning to Syria three months later, I found they had killed or driven away many of the moderate fighters, including some I had got to know.

Isis arrived with another influx of jihadists from abroad, a large number of them from the west, including from the UK, and started establishing the Islamic State. Areas changed hands rapidly.

The town of al-Bab, around 20 miles from Aleppo, where I had stayed for weeks, was a microcosm of what happened. First the moderate rebels took control, driving out regime troops from a base outside the town; then al-Nusra established themselves, and finally came occupation by Isis, and with it a savage regime of shooting, hanging and flogging. A young man who used to run a popular shisha cafe, and joked about setting up his own chain in London, was among those arrested and executed.

Isis began to kidnap and murder foreigners, aid workers and journalists. Among those killed were people I knew: Peter Kassig, an American aid worker; and two American journalists, Steven Sotloff, who I had met in Libya, and Jim Foley, a friend of 15 years who I had worked alongside in Libya, as well as Iraq and Afghanistan. Jim was beheaded by Mohammed Emwazi – “Jihadi John” – from London who had murdered a number of other hostages. Emwazi was killed by drone strike in Raqqa, the “capital” of the “Caliphate”. Some civil rights groups protested in Britain that he has not been given a fair trial.

It became extremely rare for foreign journalists to venture into rebel, basically Isis, controlled northern Syria, the reporting coming mainly from those allowed in by the Assad regime. Just one significant rebel enclave, Idlib, now remains in Syria, with around 15,000 Turkish troops present there to stop the Damascus regime from taking over.

The status quo has been reestablished in other countries of the Arab Spring. In Egypt, my colleagues and I witnessesd police shooting dead demonstrators after the elected Muslim Brotherhood government of Mohammed Morsi was overthrown in a coup by General Abdel Fattah el-Sisi.

This week, two prominent Italian recipients of the Legion of Honour, an MEP and a former minister, returned their medals in protest at Emmanuel Macron giving the award to the Egyptian president, citing the killing of an Italian student, Giulio Regeni, in Cairo while in custody, as well as other allegations of human rights abuses in Egypt.

Elections have taken place in Tunisia since the revolution and the country remains relatively stable. But the economy, heavily dependent on tourism, was hard hit by jihadist violence. Twenty-two people were killed in an attack at the Bardo Museum in Tunis and 38 others, 30 of them British, at the resort city of Sousse.

The Sousse massacre was carried out by Seifeddine Rezgui who had been shaped by the Arab Spring. The young man had celebrated when Ben Ali fell in Tunisia, had become radicalised in the struggle against Gaddafi, embittered by Assad’s violence and, at the end, inspired by Isis.

Two friends of Rezgui, Yassin and Taha, told me that Rezgui had been appalled by the retributions of Assad’s regime when the Syrian uprising began, railing at the west for betraying Syriansy, while praising al-Nusra, and then going on to declare that Isis was the right answer for Islam.

Rezgui went to Libya during the revolution against Muammar Gaddafi, accompanying men who were smuggling arms to the rebels. He went on to train at an Isis camp across the Libyan border in Sabratha before carrying out his attack.

The Gaddafi family are scattered around North Africa and the Middle East. Saif al-Gaddafi, the son who was seen as the Colonel’s heir, was captured in the aftermath of the revolution by rebels who allegedly cut off the two fingers with which he used to give victory salutes.

Saif was released from prison in Zintan in 2017. The Zintani authorities refused to transfer him to the custody of the International Criminal Court in Hague, which has a warrant out for his arrest. Saif al-Gaddafi has announced that he would run for the presidency in the Libyan elections supposedly due to take place next year. Last October, General Hafter declared that Saif had every right to put himself forward as a candidate.

Documents leaked last year showed that Russia’s Wagner Group was actively promoting Saif al-Gaddafi. It had presented him with a Power Point proposal for strategy. Wagner has restarted Jamahiriya TV, a channel which was used to disseminate his father’s view of the world, and had moved to Cairo from where it had been broadcasting intermittently. The company also set up a dozen Facebook groups promoting Saif and Haftar. The leaked papers were critical of Gaddafi as well, claiming that he had “a flawed conception of his own significance”, and needed to be diligently monitored for any project to work.