The middle-class Pakistani students fighting for a homeland dream

Advertisement

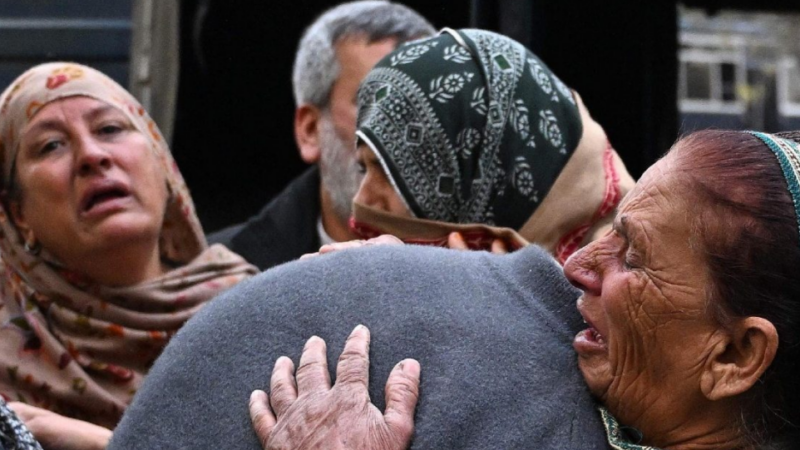

Like many other students, Sana Baloch had travelled home during the coronavirus lockdown in the spring and now, nearly three months have passed since his disappearance.

A promising postgraduate student at one of Pakistan’s top universities in Islamabad, Sana Baloch went missing on 11 May on the outskirts of a small town called Kharan.

His case is not unique – it is similar to a host of others in the desperately poor Balochistan, where Pakistan’s military is accused of a decades-long campaign to suppress aspirations for provincial autonomy.

In recent years, “internment” or “torture” centers are reported to have proliferated inside military cantonments in Balochistan. These centers are described by the Human Rights Commission of Pakistan (HRCP) as places “where people are disappeared, tortured and interrogated outside of the law”.

People with knowledge of the case say that Sana Baloch was being held at such an internment center in the town of Kharan itself. His family don’t know – or won’t say – where he is. Nor have they gone to court to press the authorities for information on his whereabouts. But it is not because of a lack of concern.

“When you live in Balochistan, you don’t do that,” said one of the sources. “You wait in silence and hope for the best – just like the parents of Shahdad Mumtaz.”

Shahdad Mumtaz, another student from Balochistan, went missing in early 2015. His family remained silent, and months later their son came back to them.

However, on May 1, 10 days before Sana Baloch went missing, Shahdad Mumtaz was killed in a shoot-out with the Pakistani military. An armed separatist group, the Baloch Liberation Army (BLA), claimed him as one of its members saying that he had died fighting “the Pakistani army and members of its proxy death squad”.

Was Shahdad Mumtaz planning on being an armed insurgent all along, keeping his secret from relatives, friends and lecturers? Could Sana Baloch be on the same path?

The answers to these questions lie in decades of troubled relations between Balochistan and Islamabad – and the impact of that history on the region’s increasingly educated youth.

Young men like Shahdad Mumtaz and Sana Baloch are born and raised in a province with vast natural wealth – Balochistan comprises 44% of Pakistan’s land area but only about 5.9% of its population, and has mineral resources estimated at more than $1 trillion – and an area where conflict has raged for decades due to its geographical contiguity to southern Afghanistan.

Shahdad Mumtaz taught at a prestigious grammar school in his home town of Turbat in the far south of the province, and worked as a regional coordinator for the HRCP.

In 2015 he joined the ranks of the missing, but he was among those lucky ones who, in the words of a local analyst, “manage to convince their captors that they have been reformed and that their nationalist activism was a mistake”.

After his release, in 2016, Shahdad Mumtaz joined Islamabad’s Quaid-e-Azam University (QAU) for a Masters’ programme, and he confided in a fellow Baloch student about his life in detention.

“He told me that the message being imparted was mainly about the ills of political activism,” the former student said, requesting anonymity for his safety. “‘End it, they would say. Take an interest in your studies, find a job. Why do you waste time shouting slogans that suit the designs of the enemies of Pakistan?'”

The message was conveyed to the interned men “through torture and abuse”, the student said. “They would kick them, beat them with sticks, hurl at them threats of death and dishonour, abuse them, keep them awake for days,” he said.

But Shahdad Mumtaz’s nationalism refused to die. It was apparent in his activities at the university. Such feelings are widely shared in Balochistan, and date back to Pakistan’s independence in 1947. When Britain partitioned India, princely states dotting the sub-continent were given options to either join India, join the new Pakistan or remain independent.

The state of Qalat, which encompassed modern-day Balochistan, declared independence. Pakistan forcibly annexed the state nine months later.

The annexation birthed a movement for Baloch rights that has increasingly drifted towards left-wing nationalism. There has been conflict ever since, fuelled by Balochi demands for a greater share of the proceeds from their vast mineral wealth.

Over the years since, the military has expanded its presence by building new garrisons and, as reported by several rights groups, funding private spy networks to detain real or suspected nationalists in the province. Activists say the army has “disappeared” those caught instead of producing them in courts of law.

It is also accused of using Islamist militants to infiltrate once secular Baloch areas to further its aims, both in Balochistan and over the border in Afghanistan.

According to estimates provided by the Europe-based Human Rights Council of Balochistan (HRCB), at least 20,000 Baloch activists have been “disappeared” since 2000, and about 7,000 of them are dead.

The Pakistani authorities routinely deny allegations of abuses in Balochistan.

In the past, the military has avoided comment on allegations of enforced disappearances, “torture centres” or extra-judicial killings.

The civilian government in the province has previously blamed the killings of hundreds of political activists and suspected armed separatists in recent years on infighting among insurgent groups.

Analysts say the sustained policy of repression, and a failure by other state institutions such as parliament and the judiciary to rein in the powerful military and address the problems in Balochistan, has caused nationalist groups to radicalize and to evolve from their tribal roots.

The middle class “is today the main target of the Pakistani military in what seems to be an attempt to eradicate all manifestations of Baloch nationalism and to rule out the very possibility of its renaissance”, said a report by the Carnegie Endowment for International Peace, a US based foreign policy think-tank, as long ago as 2013.

Shahdad Mumtaz was very much a member of that educated, urban middle class. But students who knew him say that at no point did they ever suspect he would pick up a gun and wage a war against the state. On the contrary, he completed his Masters in 2018 and enrolled for an M.Phil course. He also had plans to go to Lahore with a friend to prepare for civil service exams, the route to a career in Pakistan’s administrative elite.

But there were also times he would crack, said his student friend.

“When some activists he knew would go missing, or their mutilated bodies would be found, or when some journalist or teacher would be killed in a targeted attack, he would say, ‘Man, this state only understands the language of the gun’.”

Friends last saw him in late January, when he was headed to Lahore for his planned preparation for the civil service exams. Then on 1 May, in the gunfight in the Shorparod area of Balochistan, he lost his life.

The case of Sana Baloch appears not much different from the case of Shahdad Mumtaz, or hundreds of other Baloch activists.

He too is a staunch nationalist, and an active member of the BNP-M party. He is also an accomplished student, having completed a Masters in Balochi literature, and currently studying for an M.Phil degree at Islamabad’s Allama Iqbal Open University (AIOU).

What will happen to him now is unclear.

Will his dead body turn up dumped somewhere in the remote wilderness? Or will he come home “reformed”, lie low for a while and then take up arms against the state, as Shahdad Mumtaz did?

Advertisement