Analysis: Donald Rumsfeld’s policies have consequences that reverberate to this day

Donald Rumsfeld was one of the key figures in shaping the geopolitics of our time – playing a prominent role in taking the US into the wars in Iraq and Afghanistan, and pursuing policies that created bitter divisions at home and abroad.

The defence secretary under two US presidents, he was heavily influenced by neo-con ideologues in the George W Bush administration and helped to lay out a blueprint for America’s approach to defence and foreign affairs whose consequences reverberate to this day.

Rumsfeld, who died on Wednesday at the age of 88, was a veteran politician, a counsellor to Richard Nixon in the 1960s, a senior member of Gerald Ford’s administration and Middle East envoy under Ronald Reagan. He was also a three-term congressman, permanent envoy to Nato and White House chief of staff.

President Ford appointed Mr Rumsfeld defence secretary in 1975 in which post he saw the transition from conscription to volunteer armed forces, sought to reverse the steady decline in the defence budget, and build up the country’s military manpower and conventional and nuclear arsenal.

This led to tensions with secretary of state Henry Kissinger, who was engaged in the Salt (Strategic Arms Limitation Talks) with the Soviet Union.

Declassified transcripts of telephone conversations show Mr Kissinger urging President Ford to tell Mr Rumsfeld to “get with it” on the negotiations. There was also long-running animosity between Mr Rumsfeld and George Bush senior, who had become director of the CIA.

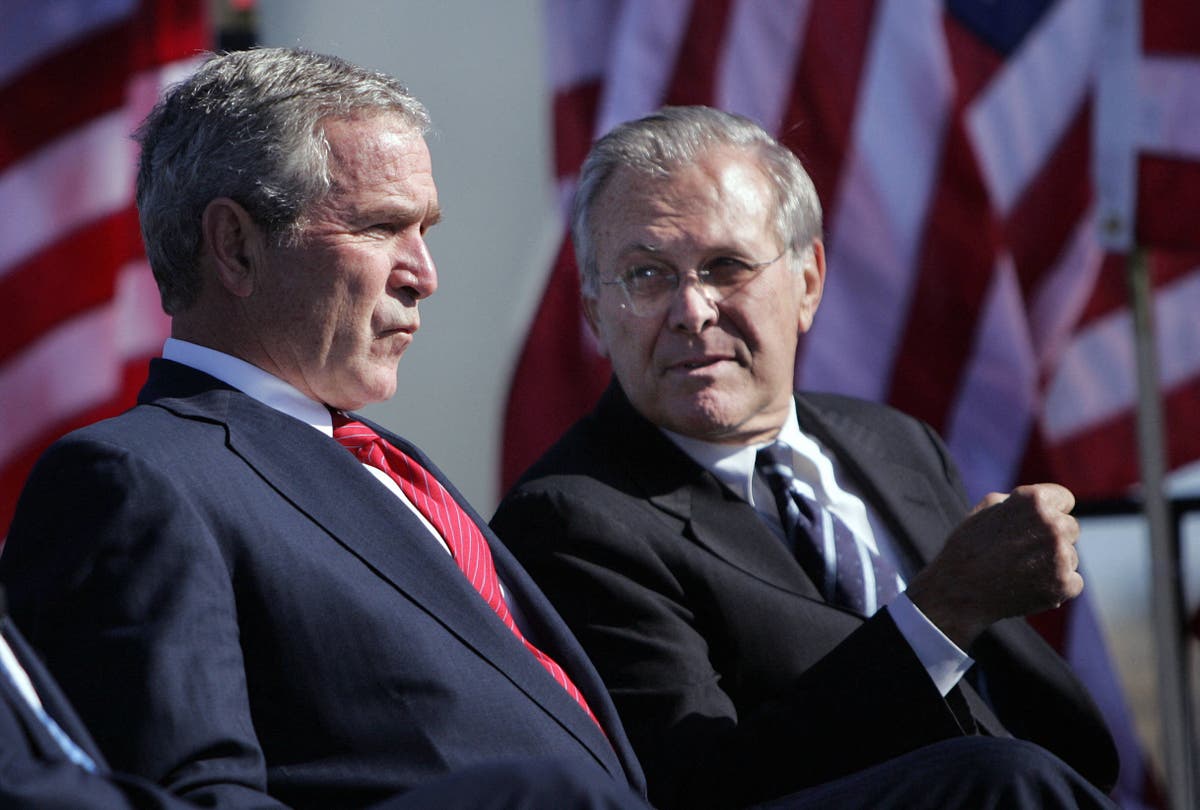

Yet Mr Bush’s son, when president, appointed Mr Rumsfeld once again as defence secretary – just before the 11 September attacks. And it was under George W Bush that Mr Rumsfeld’s influence rose to its height before later crashing down.

The Bush administration included a number of prominent neo-cons including Paul Wolfowitz, Elliott Abrams, Richard Perle and Paul Bremer. Mr Rumsfeld and vice president Dick Cheney, although not identified as neo-cons themselves, enabled their ideas – especially on supporting Israel and America’s role in the Middle-East – to be put into practice.

It was this group, aided by Tony Blair’s government in Britain, that engineered the invasion of Iraq under the false pretext of Saddam Hussein possessing weapons of mass destruction.

Any initial hope of a relatively peaceful path towards a new government disappeared when the neo-cons – with the acquiescence of Mr Rumsfeld and Mr Cheney – sent Mr Bremer to be the head of the Coalition Provisional Authority. In his capacity as effective shogun of Iraq, Mr Bremer instituted the policy of de-Baathification with disastrous consequences.

Mr Rumsfeld was fully behind the Bush administration’s earlier invasion of Afghanistan. But after the swift overthrow of the Taliban regime, and at a time when Afghanistan should have been stabilised and rebuilt, Mr Rumsfeld was among those who pushed to move vital resources to Iraq to topple Saddam Hussein. The Taliban, fed and watered by their backers in the Pakistani military and intelligence services, took advantage of the security vacuum to move back into Afghanistan.

As the situation in Iraq unravelled amid ferocious violence, Mr Rumsfeld faced rising criticism. While facing critical scrutiny over the conduct of the conflict, the Senate Armed Services Committee held him responsible for the shocking torture and abuse scandal in Abu Ghraib. Mr Rumsfeld twice offered to resign, but President Bush asked him to carry on.

In 2006, eight US and other Nato retired generals and admirals called on Mr Rumsfeld to resign accusing him of “abysmal” military planning and strategic incompetence. Their views were said to have been shared by 75 per cent of officers in the field.

Mr Rumsfeld sought to refute the charges and President Bush once again stood by him. But with criticism continuing unabated, the defence secretary resigned on the eve of mid-term elections in 2006. The news did not come out until election day, and a number of senior Republicans complained that that earlier news of his departure might have saved votes.

To an extent, Mr Rumsfeld was a scapegoat for the collective failure of the US administration in Iraq. But the policies he stuck with were fundamentally flawed and he refused to accept that he could be wrong.

It also remains the case that these policies in Iraq and Afghanistan, and the Middle East in general, contributed greatly to extremist radicalisation among Muslims fuelling the rise of al-Qaeda and Isis in the region and bringing jihad to Europe and America.

Journalists covering those wars came across Mr Rumsfeld a number of times. During a 2004 visit to Mazhar-e-Sharif, in northern Afghanistan, he told a group of reporters that the Taliban “are marginalised, they are effectively finished, they will have no future role to play in Afghanistan”.

Of course, he was not the only American or British leader who failed to foresee how things would unfold in a land invaded without adequate thought given to what was needed to repair and rebuild in the difficult aftermath.