Pakistan is third worst nation globally in terms of law and order: World Justice Project index

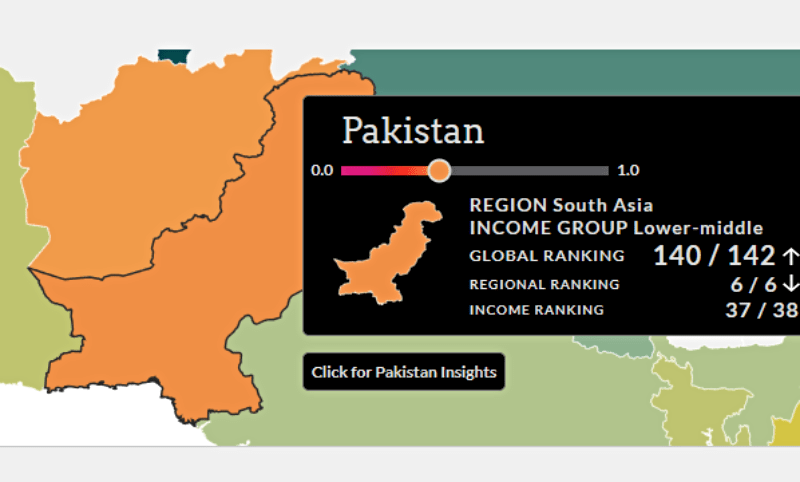

In the latest World Justice Project (WJP) Rule of Law Index for 2024, Pakistan has been ranked 140th out of 142 countries, making it the third-worst nation in terms of law and order globally.

This ranking highlights critical challenges within the country’s justice system, human rights practices, and accountability frameworks.

The Rule of Law Index assesses countries on several dimensions such as constraints on government powers, the absence of corruption, fundamental rights, order and security, regulatory enforcement, civil justice, and criminal justice.

Pakistan’s performance across these areas offers an in-depth view of the systemic problems undermining law and order in the country.

The World Justice Project evaluates 142 countries using eight core factors to rank their adherence to the rule of law. These include:

Constraints on government powers: Measures the extent to which those in power are held accountable under the law.

Absence of corruption: Evaluates the lack of corrupt practices in different sectors like the judiciary, police, executive branch, etc.

Open government: Gauges the transparency of government operations and the accessibility of public information.

Fundamental rights: Considers the level of protection of fundamental human rights.

Order and security: Measures the extent to which people experience safety from crime and political violence.

Regulatory enforcement: Evaluates the fairness and effectiveness of regulations.

Civil justice: Assesses the accessibility and fairness of civil justice systems.

Criminal justice: Considers the fairness, independence, and effectiveness of the criminal justice system.

Pakistan’s rank of 140th reveals a profound lack of law and order, widespread corruption, inefficient justice systems, and compromised fundamental rights.

Several issues are pervasive in Pakistan’s poor ranking, which can be better understood through an analysis of each dimension.

Constraints on government Powers: One of the cornerstones of the rule of law is the constraint on government powers.

In Pakistan, power is often centralized, with limited oversight or accountability. While institutions such as the judiciary and parliament theoretically function as checks and balances, political interference is rife, rendering them less effective.

The separation of powers between the executive and the judiciary is often blurred, leading to selective justice based on political influences.

Instances of executive overreach and the use of state apparatus to target political opponents are frequent in Pakistan.

High-profile cases, such as the removal of prime ministers or the persecution of opposition leaders, demonstrate the lack of independence in the judiciary.

This reality results in a skewed and politically charged justice system.

Absence of corruption: Pakistan’s ranking in the “absence of corruption” category is dismal due to the pervasive nature of corrupt practices in public institutions.

Transparency International’s Corruption Perceptions Index (CPI) also ranks Pakistan poorly in terms of corruption control.

Whether it’s the police, judiciary, or civil administration, corruption remains rampant, creating hurdles for the ordinary citizen seeking fair treatment.

Judicial corruption in Pakistan often leads to unjust outcomes for those without the financial means or connections to influence court proceedings.

Police corruption, including bribery and misuse of power, also feeds into a system where laws are selectively enforced, exacerbating distrust between citizens and law enforcement.

Open government and regulatory enforcement: The lack of transparency in government operations is a long-standing issue in Pakistan.

Information accessibility is limited, and citizens often face challenges in getting basic services.

The Right to Information Act remains under-implemented, and the government’s efforts to control the narrative through selective media reporting and censorship have only deepened concerns about accountability.

Moreover, “regulatory enforcement” in Pakistan is often inconsistent and ineffective.

Regulatory frameworks suffer from administrative inefficiencies and lack of enforcement capacity, creating an environment conducive to arbitrary decisions and favouritism.

Fundamental rights: Violations of “fundamental human rights” are a significant factor contributing to Pakistan’s low ranking.

Instances of extrajudicial killings, enforced disappearances, arbitrary detentions, and torture have been widely reported. Pakistan has faced criticism from human rights organizations for these abuses, which are often carried out with impunity.

Women’s rights, religious freedoms, and minority protections are areas where Pakistan’s performance is particularly weak.

Religious minorities often face persecution under blasphemy laws, and cases of violence against women, including honour killings and domestic abuse, are rampant, with limited recourse for victims.

Order and security: The “order and security” dimension paints a grim picture in Pakistan.

The state’s inability to effectively combat rising crime rates, militancy, and insurgency remains a key concern. In many regions, particularly the tribal areas and Balochistan, insurgent activities and sectarian violence are prevalent.

Kidnappings, targeted killings, and terrorist activities continue to undermine public confidence in the government’s ability to provide safety.

Moreover, ongoing issues in law enforcement, such as inadequate training, lack of resources, and misuse of authority, prevent the police from effectively curbing crime.

Civil and criminal justice: Access to civil justice in Pakistan is often hindered by bureaucratic delays, court backlogs, and a lack of resources.

With cases dragging on for years, citizens struggle to secure timely resolutions to disputes.

The civil justice system is marked by inefficiency, discrimination, and corruption, making it inaccessible to vulnerable communities.

The criminal justice system fares no better.

Issues such as torture in custody, arbitrary arrests, and prolonged pre-trial detentions illustrate a lack of adherence to due process.

While efforts have been made to reform the police and judiciary, their implementation remains slow and insufficient.

Implications of the ranking: The ranking of 140th out of 142 countries reflects poorly not only on Pakistan’s global standing but also on its domestic stability.

A weak rule of law has far-reaching consequences for economic growth, human development, and societal peace.

For example, it discourages foreign investment due to a lack of legal protections and trust in the regulatory environment.

Additionally, it hinders social progress by perpetuating inequalities and marginalizing vulnerable communities.

This fragile state of law and order in Pakistan also has regional implications.

It hampers regional cooperation on critical issues such as counterterrorism, border security, and drug trafficking.

The persistence of lawlessness, political instability, and human rights violations could exacerbate regional tensions and disrupt international partnerships.

Pakistan’s position as the third-worst country in terms of law and order according to the World Justice Project’s 2024 Rule of Law Index underscores a deep-seated crisis that must be addressed urgently.

From widespread corruption and lack of judicial independence to human rights abuses and political instability, the challenges are complex and multifaceted.

Without comprehensive reforms and genuine commitment from political leaders, the rule of law in Pakistan is likely to remain weak, with severe consequences for its citizens, economy, and international relations.

Addressing these issues requires more than rhetoric; it demands concerted, transparent, and inclusive efforts towards building a fairer and more just society.

“It is clear Pakistan is in dire need of major and genuine institutional reform. The path forward demands political will and unity. If there ever was a purpose for all quarters to be on the ‘same page’, it is this,” according to a recent editorial published on Pakistan’s leading English daily the Dawn.

(ENDS)