Bangladesh’s student protests: A test of Sheikh Hasina’s leadership.

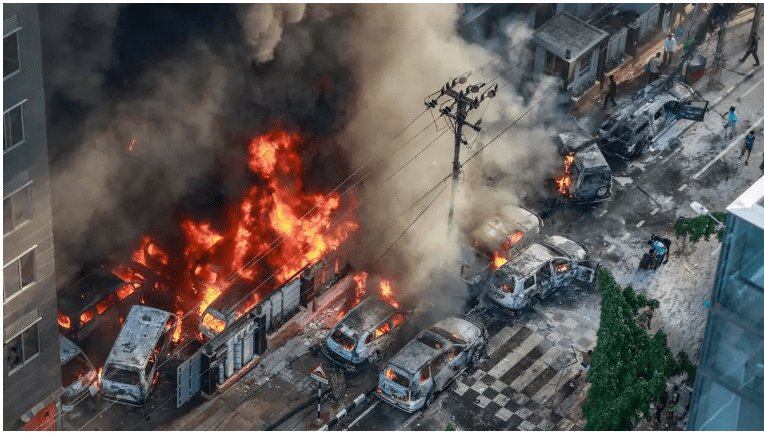

The government was caught unawares as protests over a quota for freedom fighters in jobs turned violent and claimed over 300 lives.

The rich history of student protests in Bangladesh is replete with tales of sacrifice, violence, and resolve. Students were at the forefront during the days of the “Bhasha Andolon”, the language movement of 1952, and the freedom struggle of 1971.

The language movement began with the “Urdu only” protests of 1948 in erstwhile East Pakistan. And many of its student leaders, such as Mujibur Rahman and Tajuddin Ahmad, subsequently became leading political figures in the freedom movement of 1971, alongside leaders like Maulana Abdul Hamid Khan Bhasani. All three are now revered as founding fathers of Bangladesh.

With such an illustrious heritage, where does one place the current student protests in Bangladesh that continue to shake the country?

At its height, it ran for more than a week, and there was mayhem, violence, and brutality as police and security personnel went on a shooting spree and rival factions of students clashed with each other on campuses and in the streets, damaging government property, installations and vehicles. The protests threw life out of gear in Bangladesh and raised serious questions about the stability of the Sheikh Hasina government.

As India, which shares its longest border with Bangladesh and is known to back the Awami League government, kept an eagle eye on the fast-paced developments in the neighbouring country, Prime Minister Sheikh Hasina called in the army and imposed curfew to restore normalcy.

Prime Minister Sheikh Hasina weeps while inspecting the Mirpur metro station in Dhaka, which was vandalised during the protests. | Photo Credit: BANGLADESH PRIME MINISTER’S OFFICE/AFP

With 150 officially dead, Hasina blames political opponents for violence

The violence claimed 150 lives (the official death toll released by the government on July 29) and left over 3,000 injured. There were allegations that many of the injured were hunted down in hospitals by rival students or members of state intelligence agencies.

The Prime Minister blamed inimical forces that wanted to destroy her and thwart the country’s economic growth and development. The opposition Bangladesh Nationalist Party (BNP) and the banned Islamist outfit the Jamaat-e-Islami were alleged to be behind the unrest.

The BNP and Jamaat-e-Islami have been out of power for a very long time and are marginalised in Bangladeshi politics, government supporters say. The protests allowed them an opportunity to crawl back to the political centre stage.

As Bangladesh limps back to normalcy, with Internet and mobile phone services restored, people are asking how and why the agitating students, who were for weeks protesting peacefully, suddenly turned violent and hostile.

“The term “razakar” is used for those who worked with the Pakistani army in 1971 to identify, torture, and kill freedom fighters. It is considered pejorative in Bangladesh. ”

Mahfuz Anam, editor of Bangladesh’s English-language newspaper Daily Star, wrote: “Slowly but surely, the story of the student movement for quota reform is fading from the official narrative and that of the BNP-Jamaat conspiracy to destabilise the country is gaining currency.”

He added: “In our view, both stories merit coverage and in-depth analyses. Why one is fading and the other is becoming bigger is because one suits those in power and the other embarrasses them. The blame game is on; demonising the other is in full swing.”

Protests centred around quota system

The protests were centred essentially around the demand to reform the quota system in Bangladesh. Quotas were introduced in 1972, reserving 56 per cent of government jobs for different categories. A bulky 30 per cent was reserved for freedom fighters, and there was little objection to that in the initial days of independence.

In subsequent years, the privilege was extended to the freedom fighters’ children and then their grandchildren, triggering protests. Many people questioned the wisdom of the quota, and a perception gained ground that privileges were being given in perpetuity to families of freedom fighters. The question of who merited the description of “freedom fighter” was also contested, and it was often left to those in the ruling Awami League to make a decision on this.

Protesters clashing with Border Guard Bangladesh in Dhaka on July 19. | Photo Credit: MOHAMMAD PONIR HOSSAIN/REUTERS

During a similar student agitation in 2018, Prime Minister Hasina became so disgusted with the bickering about freedom fighters that she decided to scrap the quota system. But in June this year, the High Court Division (popularly known as the “High Court”) of the Supreme Court of Bangladesh reinstated the quota system and dismissed the government order of 2018. This brought the students back on the streets. The Prime Minister decided to move the Supreme Court and challenge the High Court ruling.

On July 21, the Supreme Court of Bangladesh struck down the June ruling by the High Court Division but brought in a 5 per cent quota for freedom fighters’ descendants. The ruling also said 1 per cent of government jobs would be reserved for people of tribal communities and 1 per cent for people with disabilities or identifying as the third gender; for the remaining 93 per cent of government jobs, candidates would be judged on merit.

Highlights

- Over 150 lives were lost in Bangladesh as student protests turned violent and placed a question mark on Prime Minister Sheikh Hasina’s leadership.

- The students were protesting against a quota system that reserved 30 per cent of government jobs for descendants of freedom fighters.

- The Supreme Court of Bangladesh has now slashed the quota for freedom fighter descendants to 5 per cent.

- Prime Minister Sheikh Hasina believes that her political opponents were behind the unrest.

Two distinct phases in protests, from peaceful to violent

Many observers saw two distinct phases of the protests: a peaceful one and another that gradually turned violent in the wake of reports of the Prime Minister’s “razakar” comment on July 14. The term “razakar” is used for those who collaborated with the Pakistani army in 1971 to identify, torture, and kill hundreds of families of freedom fighters or their sympathisers. It is considered pejorative in Bangladesh.

Hasina has since denied that she compared the students to “razakars”. However, while answering questions on the protests, she said: “I don’t know why there is so much resentment against freedom fighters.” She went on to talk about the sacrifices by freedom fighters and their contribution to founding an independent Bangladesh, and added: “If the grandchildren of freedom fighters don’t enjoy the quotas, grandchildren of razakars will enjoy them.”

The Prime Minister may not have likened student protesters to razakars, but her use of the word in the context of the protests was widely interpreted by students as an attempt to identify them with razakars.

As the students’ anger spilled out of campuses, there emerged newly coined slogans such as “tumi ke, ami ke?… razakar, razakar” (Who are you and who am I? We are all razakar, razakar) or “chaite gelam odhikar, hoye gelam razakar” (We were protesting for our rights but now we are all branded as razakar). They were meant to be ironical as the students deliberately invoked this hated term to focus on their plight. The government and its supporters saw it as an act of defiance.

Cultural activists clash with the police during a song march on July 30 for people who were killed in the recent protests in Dhaka. The government had called for a day of mourning on that day, but students denounced the gesture as disrespectful. | Photo Credit: MUNIR UZ ZAMAN/AFP

As the protests turned violent, many armed youngsters started roaming the streets posing as students. It was hard to distinguish between them and genuine student protesters. The government emptied out hostels and shut all schools and educational institutions indefinitely. All scheduled examinations were cancelled, to be held only after restoration of normalcy.

Hasina, who won her fourth consecutive term as Prime Minister in January, which also made her the longest-serving leader in Bangladesh, saw the violence as the handiwork of the BNP-Jamaat combine and said the students were used as shields.

Her critics blamed her for the way the situation spiralled out of control, citing her thoughtless “razakar” comment and her decision to use the police and her Chhatra League student leaders to deal with the situation instead of engaging with the protesters herself.

“The Prime Minister could have intervened early and restrained the trigger-happy police,” said Imtiaz Ahmed, a former political science professor of Dhaka University.

Michael Kugelman, Director of the South Asia Institute in Washington, DC’s Wilson Center, felt the protests were orchestrated and led by the wider public, mostly students, but with no initial involvement from the BNP or its allies. He added that this did not mean that they had not infiltrated the protests. “Given how large and widespread the protests were, they could have easily blended in. But the government is wrong to paint these protests solely as a violent play by political thugs.”

“On the contrary, the protests reflect the anger and grievances of the public, not of a political party. Given how angry the students were about the state’s harsh response—and about state repression and corruption more broadly—the protesters’ violence was really a reflection of pure public rage, much of it pent up, against the state,” Kugelman pointed out.s

Hasina is now trying to unearth the forces that she believes have taken advantage of the student protests to launch an assault against her to destabilise her government.

Mahfuz Anam suggested that she should reach out to the students who are deeply hurt by the government’s repressive measures during the protests. “Students’ trust must be regained. A difficult task, but it must be attempted with sincerity and earnestness,” he wrote.

Sceptics however think Hasina will fall back on her tried and trusted methods. Kugelman said: “She has resorted to her usual playbook: crack down hard and blame violent opposition forces.” He said that these tactics had worked in the past. “But this time around, with the repressive response of such great scale, and having generated so much public anger, she is taking a big gamble.”

“Narendra Modi and Hasina have succeeded in forging a special bond of friendship that has led the two countries to work together in a wide range of areas.”

Many in Bangladesh and India may refuse to accept Kugelman’s position. They seriously believe that Hasina, one of the most targeted leaders in the world who has faced at least 19 attempts on her life and whose family was wiped out in a military coup, has good reason to find the masterminds behind the recent crisis. Her election victory in January was a smooth run as the BNP and most other opposition parties stayed away when the government refused to accept their demand that the election be held under a caretaker government.

In the run-up to the election, the BNP had managed to convince the US about Hasina’s democratic backsliding, and the Joe Biden administration imposed a series of sanctions on her to ensure a free and fair election. India, however, succeeded in persuading the US that the election was an “internal affair” of Bangladesh and it was left to Hasina to deal with her political opponents. The BNP and Hasina’s detractors in the West may use the violence during the student protests and the killings to convince the US and the European Union to impose fresh sanctions on her government.

India’s position on the protests

Did India’s position change after the protests? As long as the BJP is in power in India, the BNP will not be an option, said Kugelman. He pointed out that New Delhi is categorical in its belief that the BNP, and parties friendly with it like the Jamaat, represent a dangerous Islamist threat. “India will back Hasina to the bitter end,” Kugelman said.

India has facilitated the safe return of about 6,700 of its nationals, mostly students, in the wake of the disturbances. It has shown confidence in Hasina’s leadership by describing the crisis as an “internal matter”.

Narendra Modi and Hasina have succeeded in forging a special bond of friendship and cooperation that has led the two countries to work together in a wide range of areas from energy and connectivity to security and defence to trade and investment. Despite China’s growing footprint in Bangladesh in recent years, the Bangladeshi Prime Minister has managed to achieve a diplomatic balance between the two rival powers. She has also stayed unfazed by occasional taunts and derogatory remarks made by BJP leaders against Bangladesh.

India is yet to forget the “uncooperative years” of the BNP government in Dhaka. While there was negligible cooperation in the economic sector, anti-Indian elements, such as insurgent groups in India’s north-eastern region, were encouraged to operate from Bangladeshi soil.

Some BNP leaders have tried to reach out to the Modi government to persuade it that a cooperative partnership may be possible in future. But India believes that once the BNP comes to power it will not be able to resist the influence of the Jamaat and other anti-India forces.

India has high stakes in Bangladesh. It is in India’s interest to see the country stabilise under Hasina’s leadership at the earliest. A prolonged phase of violence and instability in Bangladesh can be a serious cause of concern for India. “Instability in any part of the neighbourhood is a matter of concern for India,” said Veena Sikri, a former High Commissioner to Bangladesh .

Neighbouring Myanmar has been going through a long spell of violence and instability. A similar situation in Bangladesh can expose India’s vulnerable north-eastern region, which shares borders with these two countries, to huge security challenges. India would want to prevent such a situation at its doorstep.

Pranay Sharma is a commentator on political and foreign affairs-related developments. He has worked in senior editorial positions in leading media organisations.