Al-Qaeda’s covert resurgence runs the risk of being overlooked as ISIS makes headlines.

Deadly ISIS attacks this year in Iran and the Russian capital Moscow leave little doubt about the group’s efforts at revival. ISIS is now expanding in the Middle East, Central Asia and large parts of Africa, amid warnings it may even target the United States directly in the coming months.

But it’s not just ISIS. Al-Qaeda, its rival terrorist organisation, is also in a better position to make a violent comeback.

While intelligence about ISIS and its threat potential is considered voluminous and clear, the insight into al-Qaeda’s operations is thin and conflicting. According to US intelligence assessments, by September 2023 al-Qaeda in Afghanistan had considerably declined, a year after the killing of Ayman al-Zawahiri in Kabul, leaving the group largely directionless. However, other recent evidence contradict this. Findings from a report by privately commissioned officials and recently featured in Foreign Policy show that al-Qaeda has set up military training facilities with activities appearing to resemble the group’s presence in Afghanistan before the 9/11 attacks. A UN Sanctions Monitoring Team had also similarly assessed in June 2023 that al-Qaeda is regrouping in Afghanistan.

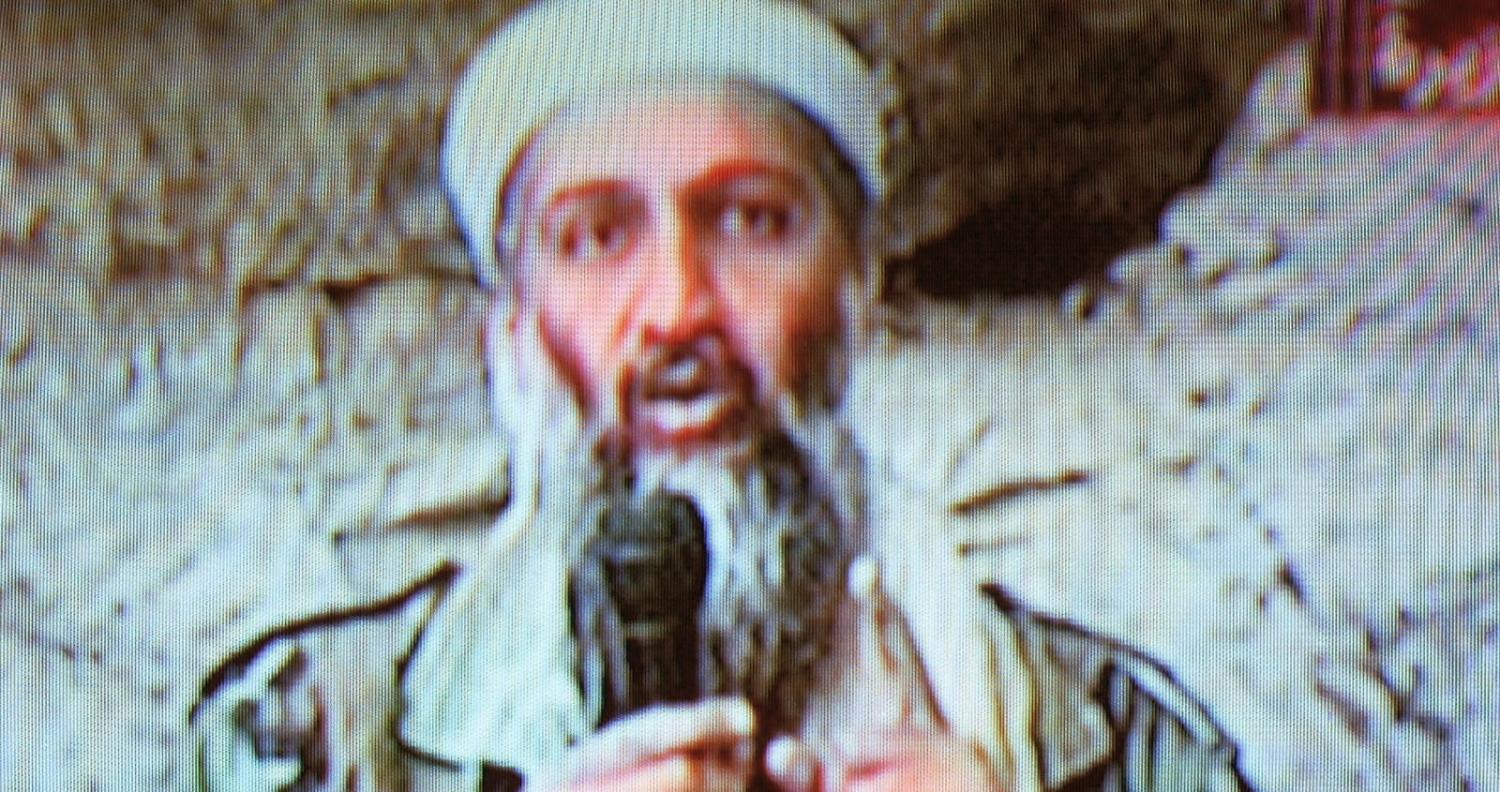

While contradictory points of intelligence paint a conflicting picture, a few verifiable developments and indicators suggest that al-Qaeda is not down and out, and that it could, in all likelihood, continue to expand. The group’s regional branch for South Asia, al-Qaeda in the Indian Subcontinent, or AQIS, has in some ways served a similar function to that of ISIS in Afghanistan, better known as IS-K, that of a calibrated regional branch that strengthens the reach of the core. Several AQIS members were arrested in India over the last year. In the January 2024 issue of the AQIS journal Nawa-i-Ghazwa-e-Hind, the group quoted Osama bin Laden’s calls for attacks against Americans.

The ambiguity about al-Qaeda’s status in Afghanistan risks creating an illusion of success against the group overall.

Meanwhile, al-Qaeda’s ally, the Tehreek-e-Taliban Pakistan (TTP), has substantially increased its attacks in Pakistan to advance Taliban and Pashtun interests. The TTP has risen to become a formidable regional organisation with expanded operations in the Pakistan-Afghanistan border region. The expansion of the TTP in Afghanistan has led to warnings that it could even “surpass Taliban’s ability to maintain stability” in the country, having developed a symbiotic nexus with several groups, such as Baloch separatist in Pakistan’s Balochistan province and a few militant groups the Khyber Pakhtunkhwa region. The TTP also uses al-Qaeda’s bases for its training activities in Afghanistan, a reflection of the two groups’ close organisational links. The region has long been a conducive environment for al-Qaeda to operate.

The United States, with its “over the horizon” counter-terrorism capabilities, can decapitate al-Qaeda’s leadership, evidenced by the killing of Osama bin Laden and Zawahiri. However, al-Qaeda has worked around this problem by significantly decentralising over the past two decades and empowering its regional affiliates. About 30 to 60 other senior members and around 2000 fighters are estimated to operate inside Afghanistan. But al-Qaeda’s current de-facto leader, Saif al-Adel, is believed to be sheltering in the relatively safety Iran, territory where a US operation via air strike or commando raid would be far more risky in terms of escalation. The Israel-Hamas conflict, which al-Qaeda considers a “battle of historical importance,” is also assumed to have seen a greater alignment in the goals of Iran and al-Qaeda.

The overall health of al-Qaeda in terms of its morale and capabilities can also be gauged by its activities in conflict zones outside of South and Central Asia. Africa is presently the biggest battleground for jihadists, and operations by al-Shabab, an al-Qaeda ally, have increased significantly in the last year in Kenya and Somalia. Al-Qaeda in the Arabian Peninsula (AQAP) remains potent in Yemen, having long been a force to be reckoned with.

The ambiguity about al-Qaeda’s status in Afghanistan risks creating an illusion of success against the group overall. Past intelligence failures about the security situation in Afghanistan underscore the need for caution. The al-Qaeda threat might be considered secondary to ISIS, but that hasn’t dented its ambition. Al-Qaeda is likely motivated to take back its position at the vanguard of a global jihad, making the danger no less deadly.