pursuing a “inclusive government” in the Afghanistan of the Taliban

Demanding the Taliban to be politically inclusive has been reduced to a mere talking point as realpolitik takes over.

This year’s Shanghai Cooperation Organization (SCO) summit was held virtually as geopolitical tensions between the organization’s members and a growing “West vs. East” narrative put New Delhi’s own diplomacy and posturing to the test. This is especially crucial since India prioritizes its G20 leadership, which will begin in September.

The ‘New Delhi Declaration’, a joint statement issued at the conclusion of the summit, provided a preview of the possibilities and difficulties that this geographically significant platform would have to face in the future. While the Russia-Ukraine war has brought forth some recent problems, older, unsolved concerns like the security and stability of Afghanistan under Taliban leadership continue to be crucial for both resistance and collaboration.

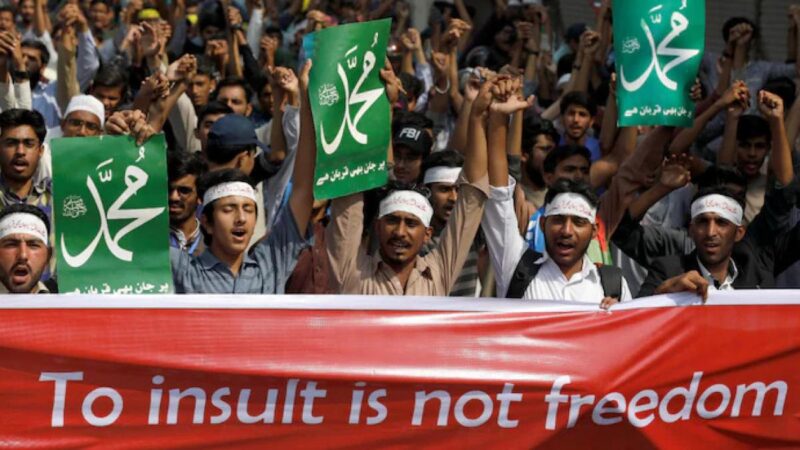

According to the New Delhi Declaration, “The Member States consider it essential to establish an inclusive government in Afghanistan with the participation of representatives of all ethnic, religious, and political groups in Afghan society.” This plea for inclusion is not new nor limited to the interests of China, Russia, or other nearby or regional powers. The significance of creating a “inclusive political structure” in Afghanistan was also emphasized in the joint statement made by Indian Prime Minister Narendra Modi and US President Joe Biden during the latter’s recent visit.

What, however, does a “inclusive government” mean in Afghanistan today? Does the West embrace the same values of inclusion as those urged by countries like Beijing and Moscow, who have even advocated for a “moderate” administration in Kabul? There don’t seem to be any solutions to this on paper, maybe on purpose. The main contention is that Pashtuns shouldn’t rule over the political hierarchy under Taliban control. According to scholar Vanda Felbab-Brown, the ‘new’ Kabul has “turned highly repressive to all forms of opposition” because of its Pashtun focus.

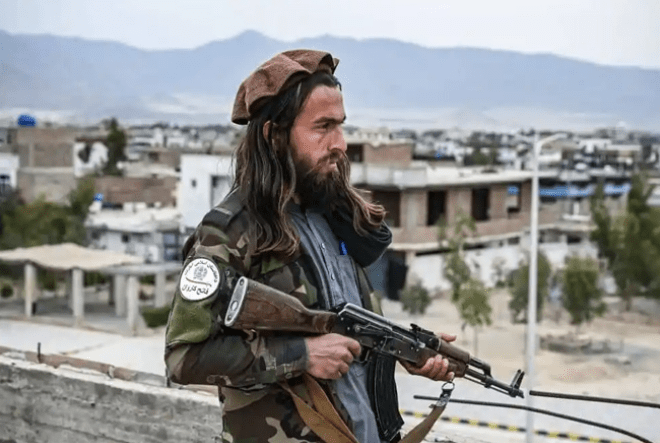

The drive for racial equality in Afghanistan has pros and cons. When the US reached a settlement with the Taliban in 2020, thus putting an end to the 20-year conflict, the Taliban emerged victorious in 2021 as an extreme ideological insurgency. The traditional saying, “You have the watches, we have the time,” which is often ascribed to the Taliban, actually come to pass. The Taliban movement, although being victorious, is divided about the degree of cooperation it wants to have with the outside world. Hibatullah Akhundzada, the Taliban’s supreme leader, is often found to disagree with his Kabul-based comrades over making ideological sacrifices in return for political legitimacy from the forces they battled against for years to uphold their ideological choice.

For the time being, there is a difference between idealistic and practical calls for diversity. First of all, the kind of “inclusivity” that is being desired has not been specified by any state or confluence, such as the SCO. The expectation of this inclusion is at variance with current reality given that the area is home to several ethnic origins, many of whom are represented in Afghanistan in some capacity. Furthermore, it is quite improbable that many governments or political figures would speak out in favor of the sort of political system they like. For instance, the Taliban named Maulvi Mahdi as a shadow district governor in November 2021. Mahdi was a Shiite leader who belonged to the ethnic Hazara community and who also served as the intelligence director for the Hazara-dominated Bamyan province in central Afghanistan. This was extensively portrayed as the Taliban being more receptive to ‘others’ and granting them authority places in the new temporary government, although at the margins of such authority. This provided a favorable story to the world community as well as Iran, the center of Shiite Islam and Afghanistan’s neighbor. The agreement did not last long, however, since Mahdi was assassinated in August 2022 while attempting to flee to Iran after getting into a dispute with the Taliban over ownership of rich mines. Given that 10-15% of the population is Shia, Tehran has been one of the most outspoken in urging the Taliban to provide political equality to all ethnic groups.

Beyond the internal dynamics of Afghanistan, most of the nations in the area do not have overlapping geopolitical interests, which makes it difficult to advance a regional consensus-driven agenda, either inside the SCO or outside of it. The majority of regional capitals are seeing the return of Afghanistan under Taliban authority from the standpoint of their own national security. With the immediate goal of maintaining calm on the border and preventing the internal collapse of the Afghan state, which may ignite an intra-ethnic and intra-tribal civil war, numerous governments in Central Asia, for instance, established lines of diplomacy and commerce with the new Islamic Emirate (IEA) leadership. For nations like Uzbekistan, Tajikistan, Iran, and Pakistan, among others, it would be difficult to avoid being involved in such a war, which would also cause a refugee and humanitarian catastrophe.

Given the lack of any realistic alternatives, demands for inclusion could be the greatest way to exert strategic pressure without having any negative tactical effects. Iran uses this as a part of its approach to the IEA, where it advocates for political unity while simultaneously maintaining full diplomatic and political ties with the Taliban leadership. However, Pakistan, which has developed Islamist organizations as part of its state policy, notably in Afghanistan, is now seeing the fallout that many have constantly warned about. The potential of the Afghan Taliban’s protectorate, the pro-Pashtun Tehrik-e-Taliban Pakistan, to strike Pakistan has now compelled Pakistani Prime Minister Shehbaz Sharif to refer to terrorism as a “hydra-headed monster” during the SCO summit. It was assumed that this would be done without any irony.

Demanding the Taliban to be politically inclusive has been reduced to a mere talking point as realpolitik takes over. The Taliban’s ongoing efforts, among other things, to exclude women from employment in the nation, serve as an example of how the Afghan people are still on the losing end more than anybody else. For the time being, the Taliban will at least fend off any immediate challenge to its hegemony if it can provide an acceptable level of regional security, which is a huge task in and of itself given the movement’s history of receiving support from and attracting a variety of other jihadist groups, including the likes of Lashkar-e-Taiba and Jaish-e-Mohammed.