Afghanistan: Inside Joe Biden’s decision to end America’s longest war

A few weeks after Joe Biden was sworn in as Barack Obama’s vice president, he held a private dinner.

The location was his official residence in the grounds of the Naval Observatory in Washington DC, a landmark in the city for more than a hundred years. The topic up for discussion was Afghanistan.

The half-dozen guests were US experts on the country and its reputation as the “graveyard of empires” – first for the British empire, whose troops tried and failed in the first half of the 19th century to seize it; and then for the Soviet Union, which invaded in 1979, triggering a massive insurgency led by mujahideen fighters and backed by the CIA. Its forces left a decade later, having lost at least 15,000 men, with 50,000 injured. (The Islamist fighters, among them a young Osama Bin Laden, suffered 90,000 casualties.)

By February 2009, when Biden held that dinner, it was becoming such a place for the United States.

Memories fade over a dozen years. Some of those who attended cannot, for instance, remember what Biden served for dinner, though they recall his wife, Jill Biden – now the first lady but then the second lady – saying hello to the group when she returned home from an evening engagement.

On one issue, however, there is utter clarity: Afghanistan was not a place where Biden thought more Americans should be losing their lives.

“He started by saying, ‘Don’t tell me we’re there to reform the whole society and stuff,’” Barnett Rubin, director at the Centre on International Cooperation at New York University, and one of the experts on Afghanistan who was present that evening, tells The Independent. “‘We’re not going to use our young men for that.’”

By that stage the US had 67,000 troops in Afghanistan, but America’s original mission – capturing or killing Bin Laden – looked like a lost cause. The US, Britain and other allied forces were confronting increased and persistent military opposition from the Taliban and al-Qaeda.

And though America had already lost around 600 men in that war, Barack Obama, recently sworn in as president, was under intense pressure from his military commanders to send more soldiers to join the battle.

Later that year, Obama did just that, dispatching 33,000 personnel to bring the total of American troops to 100,000, with large numbers of additional private contractors, employed by the CIA or State Department.

The president’s hope had been that by agreeing to “the surge” in troop numbers, he would be able more quickly to order their withdrawal.

“I do not make this decision lightly,” he said in a half-hour address from the West Point Military Academy in New York. “Let me be clear: none of this will be easy. The struggle against violent extremism will not be finished quickly, and it extends well beyond Afghanistan and Pakistan. It will be an enduring test of our free society, and our leadership in the world.”

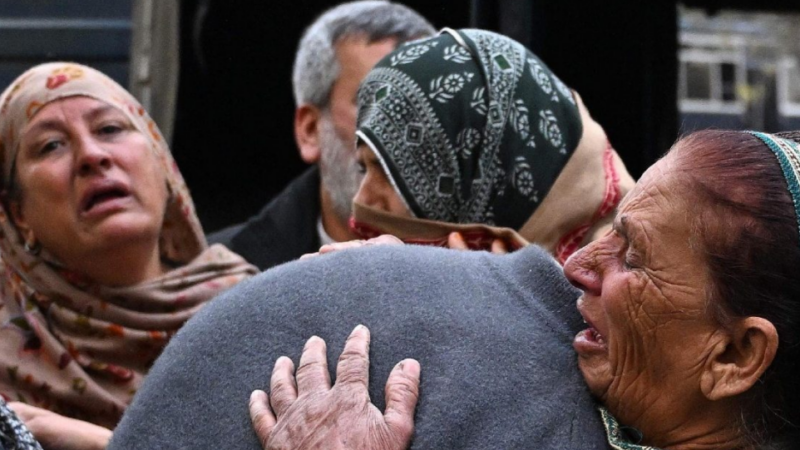

There is concern over the plight of women and young girls in the absence of US forces (Getty)

A dozen years later, Biden found himself president rather than someone’s deputy. He appeared determined to avoid repeating that previous policy, even though it was the product of an administration he had been part of and something in which he would become inextricably involved. Since he had held that dinner at the official residence, located half a mile from the British embassy, plenty had changed.

The total number of US and coalition troops in Afghanistan stood at 2,500, while the number of American casualties had risen to at least 2,372.

At least 250,000 Afghans had lost their lives, with 3 million displaced internally and 2.1 million leaving the country, mainly for Pakistan and Iran. In 2001, the population of the country was estimated at 37.5 million, while today it stands at 38 million.

Strategic momentum appears to be sort of with the Taliban

The price tag for the 20-year war stands at somewhere close to $2 trillion. Critics say there is little to show for it.

And while the US in 2011 located and killed Bin Laden in neighbouring Pakistan – his having fled Afghanistan very quickly after western forces invaded – Taliban and extremist forces are now resurgent.

A US general recently suggested that the insurgents control as many as half of the country’s district centres. “Strategic momentum appears to be sort of with the Taliban,” Gen Mark Milley, the chair of the Joint Chiefs of Staff, recently told reporters in Washington.

He said more than 200 of the 419 district centres were under Taliban control. A month earlier, he had said the Taliban controlled just 81 of them. Yet he claimed that a Taliban “automatic military takeover is not a foregone conclusion”, referring to the estimated $90bn spent training the Afghan security forces.

“The two most important combat multipliers actually are will and leadership. And this is going to be a test now of the will and leadership of the Afghan people, the Afghan security forces, and the government of Afghanistan,” he said.

Another major difference is that Joe Biden inherited a deal for the US military to withdraw, which was brokered by his predecessor, Donald Trump.

When Trump campaigned for the presidency, the former reality television star broke with many Republican orthodoxies, including on foreign policy issues. Among his stances was a determination that US troops should be brought home from both Iraq and Afghanistan, though perhaps not immediately.

Since the attacks of 9/11, the US operations in both countries had been viewed by much of the Washington establishment through the prism of the broader so-called “war on terror”.

“We made a terrible mistake getting involved there in the first place,” Trump told CNN in October 2015. “It’s a mess, it’s a mess and at this point we probably have to [leave US troops in Afghanistan] because that thing will collapse in about two seconds after they leave.”

By February 2020, the US and the Taliban had brokered a deal during talks in Qatar, to end the conflict and for America to withdraw. Pointedly, the deal did not include representatives of the US-backed Afghan government.

“I really believe the Taliban wants to do something to show that we’re not all wasting time,” Trump said in Washington after the agreement was signed.

“If bad things happen, we’ll go back.”

✕ Biden feared continued US military presence in Afghanistan would never end

During his campaign for the presidency – his third run at the job – Biden also made clear his views on Afghanistan.

He wanted troops out too, though, as with many things, he sought to avoid being nailed down to a rigid timetable. There was speculation he might opt to retain a small counterterrorism force in the country.

“Americans are rightly weary of our longest war; I am, too. But we must end the war responsibly, in a manner that ensures we both guard against threats to our homeland and never have to go back,” he said in September 2020.

Anyone looking for proof of Biden’s opinions on the matter was pointed to the journalist George Packer’s biography of US diplomat Richard Holbrooke, who served as Obama’s special envoy for Afghanistan and Pakistan until he died in December 2010.

The book, Our Man: Richard Holbrooke and the End of the American Century, quotes a private meeting between Biden and the diplomat, in which Holbrooke argued against a US withdrawal from Afghanistan.

Biden, whose son Beau had deployed to Iraq for a year in 2008 as a major with the Delaware Army National Guard, reportedly told Holbrooke: “I am not sending my boy back there to risk his life on behalf of women’s rights; it just won’t work, that’s not what they’re there for.”

Biden had not always been opposed to the US’s military effort in Afghanistan. In September 2001, when al-Qaeda attacked New York and Washington, killing almost 3,000 people and delivering an agonising gut-punch to the nation, Biden was a member of the Senate and chair of its Foreign Relations Committee.

Shortly afterwards, he, along with almost every member of Congress, voted in favor of the Authorisation for Use of Military Force, a piece of legislation that gave George W Bush power to invade Afghanistan, to topple the Taliban leadership that had hosted Bin Laden.

The sole member of both chambers to vote against was Democratic congresswoman Barbara Lee. The California congresswoman was concerned about the vagueness of the language of the resolution, fearful that Bush and neoconservative supporters would use that to expand its original intention.

Biden said the war had now crossed into two generations (AFP/Getty)

Two years later, when the same legislation was used to invade Iraq in a war premised on false intelligence about Saddam Hussein’s alleged possession of weapons of mass destruction, Lee found she had company.

But Biden, along with Hillary Clinton, voted in favour of the invasion. By 2005, when it had long since become clear that Saddam had no such weapons, Biden and others were calling their vote a mistake.

In late 2005, he told NBC News he believed the US had six months to turn around a deteriorating situation in its military operation in Iraq, and said of his 2002 vote to empower Bush: “It was a mistake. It was a mistake to assume the president would use the authority we gave him properly.”

This April, Biden told the nation that he was bringing the troops home.

Biden was able to implement what was in his heart, because the context has changed

Despite pressure from senior military commanders to retain the 2,500-odd personnel it still had there to give Afghan forces more time to fully take responsibility, he stuck to the plan he had set for himself.

“War in Afghanistan was never meant to be a multi-generational undertaking,” Biden said in a 15-minute address from the White House.

“We were attacked. We went to war with clear goals. We achieved those objectives.”

He said he was now the fourth president to have been commander in chief of US troops in Afghanistan.

“We cannot continue the cycle of extending or expanding our military presence in Afghanistan, hoping to create ideal conditions for withdrawal, and expecting a different result,” he said.

In July, images of Bagram air base, empty and abandoned after the US departure in the middle of the night, underscored the reality of what had taken place.

The base, which was rapidly pored over by Afghans in search of scrap or equipment to sell, had not just operated as the major entry and exit point for coalition forces over two decades. It was also one of many “black sites” where the CIA tortured prisoners to extract information about Bin Laden or other terror leaders.

Biden was among those watching the 2011 US military operation that killed Bin Laden (Getty)

Hundreds of alleged terrorists, swept off the battlefields or sold for bounties to the US by Pakistani intelligence, were flown from Bagram to Guantanamo Bay, even though no evidence was held on the vast majority of them.

Of the 800 men once held at the prison camp on the tip of Cuba, 40 remain. Perhaps ten men, among them Khalid Sheikh Mohammed, have been charged, and two decades after the twin towers were brought down in a cascade of horror, proceedings against those charged are still at a preliminary stage.

Both Biden and Obama vowed to close the prison.

Defending the decision to withdraw US troops from Afghanistan, Biden said this summer: “Let me ask those who wanted us to stay: how many thousands more of America’s daughters and sons are you willing to risk? How long would you have them stay?”

While most Republicans were silent, there were some high-profile critics.

George W Bush, the man who had pushed for the invasions of Afghanistan and Iraq, and who now spends his time painting and working with groups that help injured military veterans, claimed Afghan women and girls will “suffer unspeakable harm”.

In an interview with German broadcaster Deutsche Welle he was asked if the move was a mistake. “You know, I think it is, yeah, because I think the consequences are going to be unbelievably bad,” he said.

Laurel Miller, a former State Department specialist on Pakistan and Afghanistan, says Biden had long been opposed to the presence of US troops.

She says it appeared that his decision to keep a small counterterrorism force in the country had been dropped once it was judged it was not a viable stand-alone policy option, and the Taliban would not agree to it.

Troops were initially dispatched in the aftermath of the 9/11 terror attacks (Getty)

Miller, director of International Crisis Group’s Asia programme, says Biden is not in any doubt that the security situation in Afghanistan will likely get worse once US troops left.

“Instead he judged that, although undesirable, that deterioration of conditions in Afghanistan is tolerable for US national security interests,” says Miller.

Another factor helping make it easier for Biden is that, because Trump’s primary foreign policy concern was immigration and building a wall on the US’s southern border, Americans were able to step away from the shadow of 9/11 and a national obsession with counterterrorism.

“Biden was able to implement what was in his heart, because the context has changed,” says Vali Nasr, professor of international affairs and Middle East studies at Johns Hopkins School of Advanced International Studies in Washington.

Nasr, who served as a senior advisor to Holbrooke at the State Department, says Obama also wanted to get out of Afghanistan, close Guantanamo and have the Department of Justice take over the prosecution of the 9/11 plotters from the Department of Defence.

He adds: “Obama could not implement what was in his heart, because he was in the headwinds of domestic American political pressure.”

Medea Benjamin is among those who were opposed to the US invasion of Afghanistan and repeatedly called for the withdrawal of the troops. A veteran peace and women’s rights activist, Benjamin, co-founder of CodePink, does not doubt that the Afghan people face fraught and challenging times.

She is adamant, however, that things cannot improve in the longer term while American soldiers are there. Their presence has given the Afghan armed forces and authorities an excuse not to step up, and has also contributed to massive corruption, she says.

“We’ve always been working with peace groups and women’s groups in Afghanistan and we’ll continue to do that. We feel that it’s unfortunate the Taliban is as strong as it is, but it’s been strong for quite a long time now,” she says, when asked how US activists can help ordinary Afghans.

“Our friends in Afghanistan often say to us, they’re fighting on many fronts – they’re fighting the Taliban, they’re fighting the warlords, they’re fighting their own corrupt government, and they’re fighting outside forces,” she says.

“Well, now there’ll be fewer outside forces there, and that’s one less thing for them to be focusing on.”