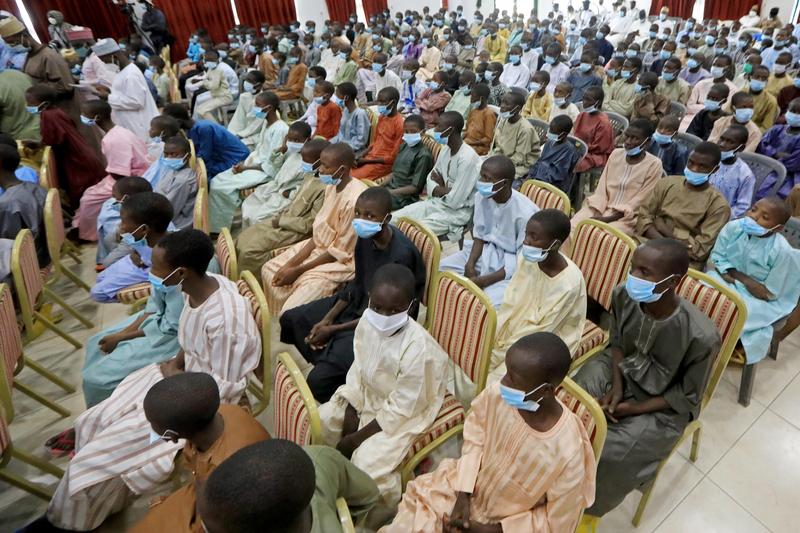

LAGOS (Reuters) – The kidnap of 344 schoolboys in northwest Nigeria had the appearance of an Islamist militant attack. There was even a video purporting to show some of the boys with members of Boko Haram, the extremists behind the 2014 kidnapping of more than 270 schoolgirls in the northeast.

FILE PHOTO: Muhammed Bello, a rescued student, is carried by his father as his relatives celebrate after he retuned home in Kankara, Nigeria, December 19, 2020. REUTERS/Afolabi Sotunde

But four government and security officials familiar with negotiations that secured the boys’ release told Reuters the attack was a result of inter-communal feuding over cattle theft, grazing rights and water access – not spreading extremism.

The mass abduction of children in Katsina state would mark a dramatic turn in clashes between farmers and herders that have killed thousands of people across Africa’s most populous nation in recent years, posing a challenge to authorities also battling a decade-long Islamist insurgency in the northeast.

Officials in Katsina and neighbouring Zamfara, where the boys were released after six days, said the attack was carried out by a gang of mostly semi-nomadic ethnic Fulanis, including former herders who turned to crime after losing their cows to cattle rustlers.

“They have local conflicts that they want to be settled, and they decided to use this (kidnapping) as a bargaining tool,” said Ibrahim Ahmad, a security adviser to the Katsina state government who took part in the negotiations through intermediaries.

Such groups are known more for armed robberies and small-scale kidnappings for ransom.

Cattle herders in the northwest are mainly Fulani, whereas farmers are mostly Hausa. For years, farmers have complained of herders letting their cows stray on to their land to graze, while herdsmen have complained their cows are being stolen.

NEGOTIATIONS

Dozens of gunmen arrived on motorcycles at the Government Science Secondary School on Dec. 11 in the town of Kankara in Katsina. They marched the boys into a vast forest that extends from Katsina into Zamfara.

Officials in both states told Reuters they established contact with the kidnappers through their clan, a cattle breeders’ association and former gang members who participated in a Zamfara amnesty programme.

The intermediaries met the kidnappers in Ruga forest on several occasions before they agreed to release the boys, according to Zamfara Governor Bello Matawalle and security sources including Ahmad.

The gang accused vigilante groups, set up to defend farming communities against banditry, of killing Fulani herders and stealing their cows, Matawalle and Ahmad said. They also made similar accusations against members of a Katsina state committee set up to investigate cattle theft, Ahmad added.

He said he was not aware of any such incidents, but said a police investigation had been launched. No ransom was paid for the boys’ release, according to officials in both states.

Reuters could not reach the gang for comment. A spokesman for the herders’ association, the Miyetti Allah Cattle Breeders’ Association of Nigeria, declined to discuss the negotiations.

BOKO HARAM?

Gangs such as these have carried out attacks across the northwest, making it hard for locals to farm, travel or tap rich mineral deposits in some states. They were responsible for more than 1,100 deaths in the first half of 2020 alone, according to rights group Amnesty International.

Boko Haram, based in the northeast, has sought to forge alliances with some of them and released videos this year claiming to have received pledges of allegiance, said Jacob Zenn, a Nigeria expert at the U.S.-based Jamestown Foundation think tank.

A man identifying himself as Boko Haram leader Abubakar Shekau claimed responsibility for the schoolboys’ kidnappings in an unverified audio recording. Soon after, the video started circulating on social media.

However, one boy who spoke in the video later told Nigeria’s Arise television that he did not believe the kidnappers when they told him to say he was being held by Boko Haram.

“Sincerely speaking, they are not Boko Haram… They are just small and tiny, tiny boys with big guns,” said the boy, who did not give his name.

Nigerian Information Minister Lai Mohammed also dismissed Boko Haram’s claim at a Dec. 18 news conference, saying: “They just want to claim that they are still a potent force.

“The boys were abducted by bandits, not Boko Haram,” Mohammed said.

Independent security experts said the kidnappers appeared to have drawn inspiration from the militants and may have received advice, but most were sceptical of any direct involvement.

Cheta Nwanze, lead partner at Lagos-based risk consultancy firm SBM Intelligence, said direct Boko Haram involvement was unlikely because of the “logistics of getting to an area that is unfamiliar” to them.

“It’s beyond their current capabilities,” he said. “The northwest is an ungoverned area controlled by other groups.”

SECOND KIDNAP

Tension between farming and herding communities has been growing in the northwest, where population growth and climate change have increased competition for resources, analysts said.

The day after the boys were returned to their families in Kankara and other towns, another gang briefly abducted some 80 students who were returning from a trip organised by an Islamic school.

The kidnappers released the children after a gunfight with police and a local vigilante group, state police said.

“All the bandits were Fulanis and are over 100 in number,” Abdullahi Sada, who led the vigilantes, told Reuters.

He said some of his men were armed with bows and arrows while others had guns made by local blacksmiths.

He denied any knowledge of attacks by vigilantes against Fulani herders, saying: “I have no idea of any such thing happening in my area.”

Nastura Ashir Shariff, who chairs the Coalition of Northern Groups (CNG), an influential civil society group, blamed a scarcity of police for such clashes, saying communities were taking law enforcement into their own hands.

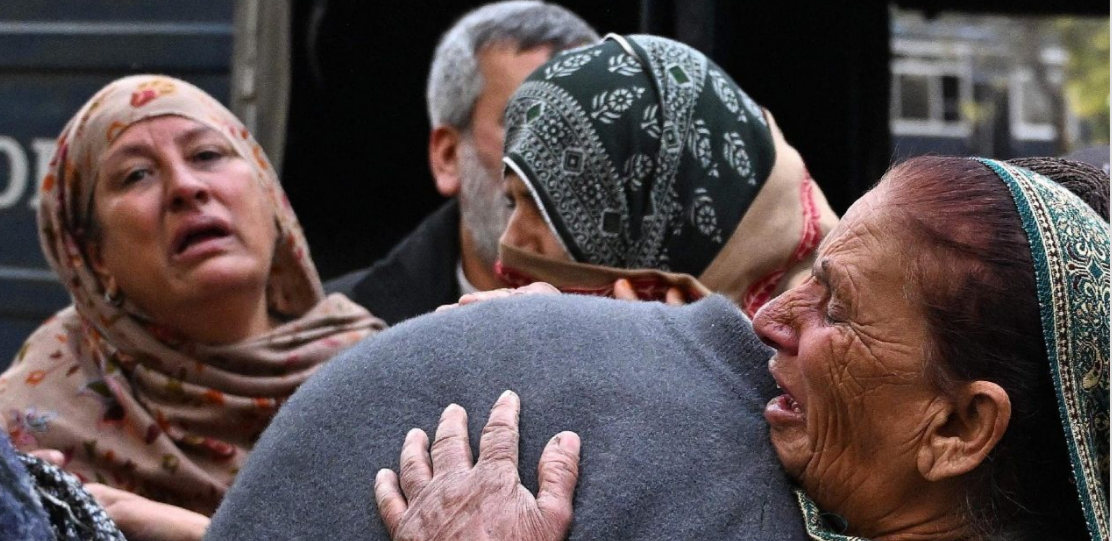

Whoever was responsible for the Kankara kidnappings, Ummi Usman, whose 14-year-old son Mujtaba was among those captured, said she was not sure whether to send him back to school.

“He is still in extreme fear whenever he remembers what they went through at the hands of their abductors,” she said. “Some of them were threatening the students that they will be back.”

(This story has been refiled to fix reporting credits)